XCIX

It was now the end of July, and by the end of August the Deraa expedition must be on the road. In the meantime Buxton’s Camel Corps had to be guided through their programme, Nuri Shaalan warned, the armoured cars taught their road to Azrak, and landing-grounds found for aeroplanes. A busy month. Nuri Shaalan, the furthest, was tackled first. He was called to meet Feisal at Jefer about the seventh of August. Buxton’s force seemed the second need. I told Feisal, under seal, of their coming. To ensure their having no casualties, they must strike Mudowwara with absolute surprise. I would guide them myself to Rumm, in the first critical march through the fag-ends of Howeitat about Akaba.

Accordingly I went down to Akaba, where Buxton let me explain to each company their march, and the impatient nature of the Allies whom they, unasked, had come to help; begging them to turn the other cheek if there was a row; partly because they were better educated than the Arabs, and therefore less prejudiced; partly because they were very few. After such solemnities came the ride up the oppressive gorge of Itm, under the red cliffs of Nejed and over the breast-like curves of Imran—that slow preparation for Rumm’s greatness—till we passed through the gap before the rock Khuzail, and into the inner shrine of the springs, with its worship-compelling coolness. There the landscape refused to be accessory, but took the skies, and we chattering humans became dust at its feet.

In Rumm the men had their first experience of watering in equality with Arabs, and found it troublesome. However, they were wonderfully mild, and Buxton was an old Sudan official, speaking Arabic, and understanding nomadic ways; very patient, good-humoured, sympathetic. Hazaa was helpful in admonishing the Arabs, and Stirling and Marshall, who accompanied the column, were familiars of the Beni Atiyeh. Thanks to their diplomacy, and to the care of the British rank and file, nothing untoward happened.

I stayed at Rumm for their first day, dumb at the unreality of these healthy-looking fellows, like stiff-bodied school boys in their shirtsleeves and shorts, as they wandered, anonymous and irresponsible, about the cliffs which had been my private resort. Three years of Sinai had burned the colour from their tanned faces, in which the blue eyes flickered weakly against the dark possessed gaze of the Beduin. For the rest they were a broad-faced, low-browed people, blunt-featured beside the fine-drawn Arabs whom generations of inbreeding had sharpened to a radiance ages older than the primitive, blotched, honest Englishmen. Continental soldiers looked lumpish beside our lean-bred fellows: but against my supple Nejdis the British in their turn looked lumpish.

Later I rode for Akaba, through the high-walled Itm, alone now with six silent, unquestioning guards, who followed after me like shadows, harmonious and submerged in their natural sand and bush and hill; and a homesickness came over me, stressing vividly my outcast life among these Arabs, while I exploited their highest ideals and made their love of freedom one more tool to help England win.

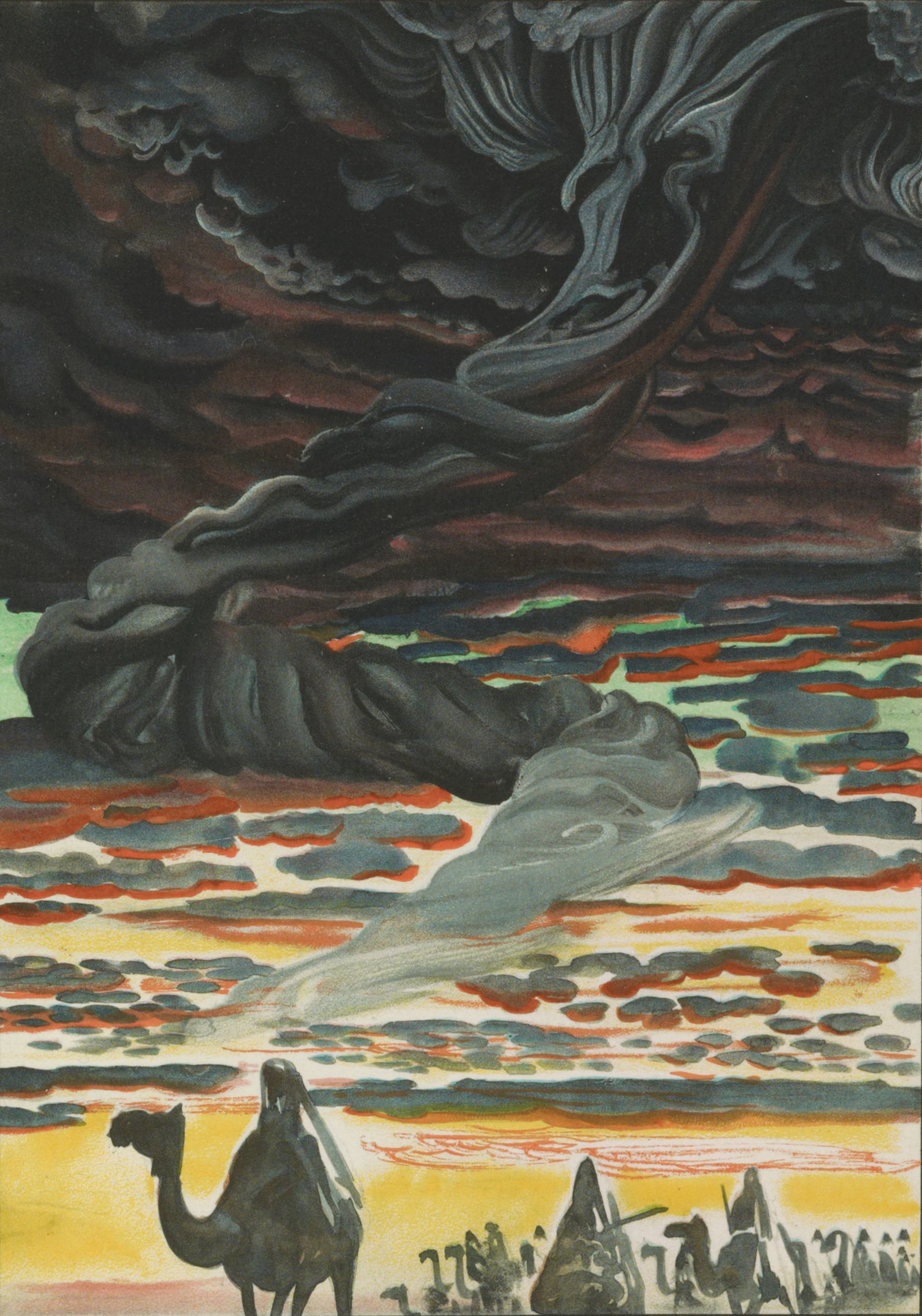

It was evening, and on the straight bar of Sinai ahead the low sun was falling, its globe extravagantly brilliant in my eyes, because I was dead-tired of my life, longing as seldom before for the moody skies of England. This sunset was fierce, stimulant, barbaric; reviving the colours of the desert like a draught—as indeed it did each evening, in a new miracle of strength and heat—while my longings were for weakness, chills and grey mistiness, that the world might not be so crystalline clear, so definitely right and wrong.

We English, who lived years abroad among strangers, went always dressed in the pride of our remembered country, that strange entity which had no part with the inhabitants, for those who loved England most, often liked Englishmen least. Here, in Arabia, in the war’s need, I was trading my honesty for her sustenance, inevitably.

In Akaba the rest of my bodyguard were assembled, prepared for victory, for I had promised the Hauran men that they should pass this great feast in their freed villages: and its date was near. So for the last time we mustered on the windy beach by the sea’s edge, the sun on its brilliant waves glinting in rivalry with my flashing and changing men. They were sixty. Seldom had the Zaagi brought so many of his troop together, and as we rode into the brown hills for Guweira he was busy sorting them in Ageyl fashion, centre and wings, with poets and singers on the right and left. So our ride was musical. It hurt him I would not have a banner, like a prince.

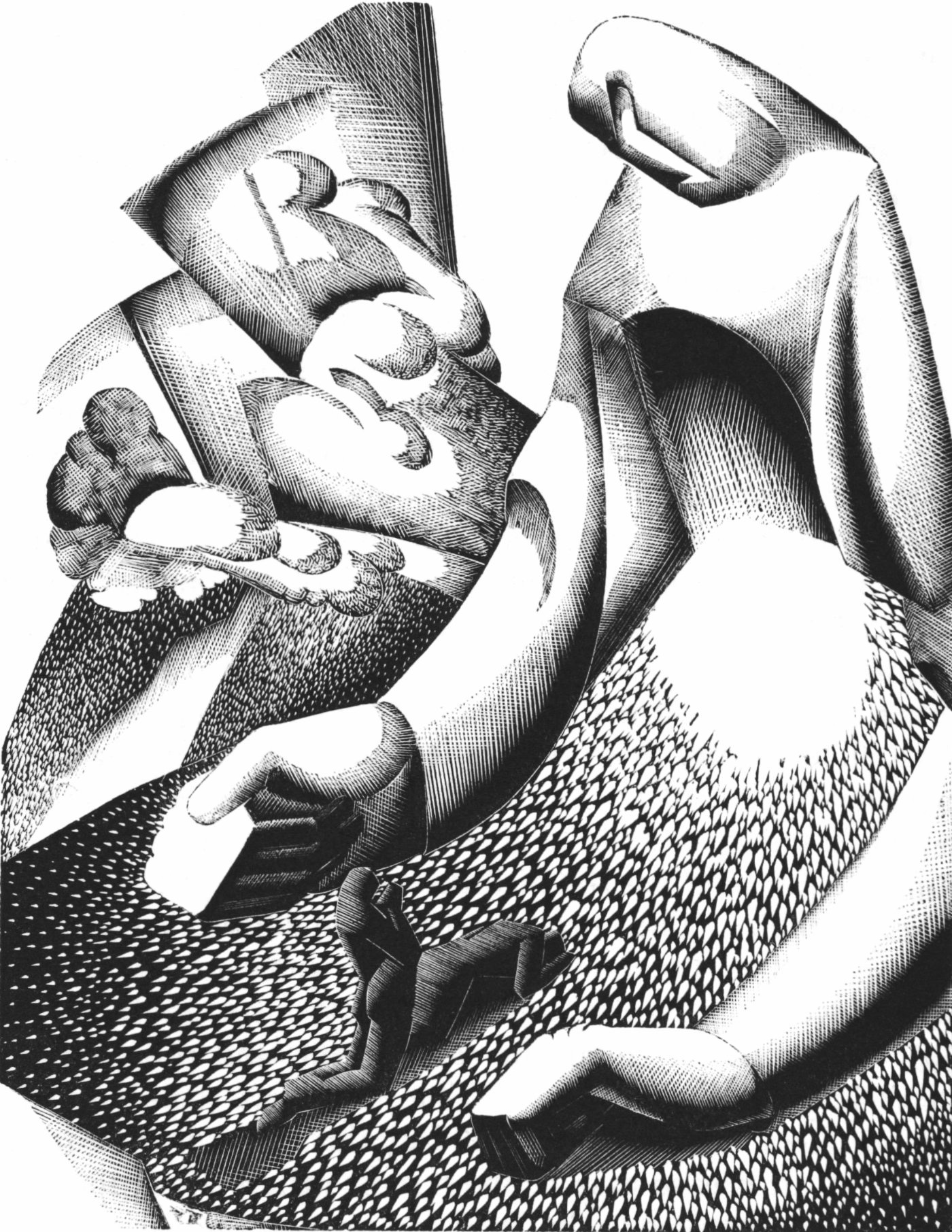

I was on my Ghazala, the old grandmother camel, now again magnificently fit. Her foal had lately died, and Abdulla, who rode next me, had skinned the little carcase, and carried the dry pelt behind his saddle, like a crupper piece. We started well, thanks to the Zaagi’s chanting, but after an hour Ghazala lifted her head high, and began to pace uneasily, picking up her feet like a sword-dancer.

I tried to urge her: but Abdulla dashed alongside me, swept his cloak about him, and sprang from his saddle, calf’s skin in hand. He lighted with a splash of gravel in front of Ghazala, who had come to a standstill, gently moaning. On the ground before her he spread the little hide, and drew her head down to it. She stopped crying, shuffled its dryness thrice with her lips; then again lifted her head and, with a whimper, strode forward. Several times in the day this happened; but afterwards she seemed to forget.

At Guweira, Siddons had an aeroplane waiting. Nuri Shaalan and Feisal wanted me at once in Jefer. The air was thin and bumpy, so that we hardly scraped over the crest of Shtar. I sat wondering if we would crash, almost hoping it. I felt sure Nuri was about to claim fulfilment of our dishonourable half-bargain, whose execution seemed more impure than its thought. Death in the air would be a clean escape; yet I scarcely hoped it, not from fear, for I was too tired to be much afraid: nor from scruple, for our lives seemed to me absolutely our own, to keep or give away: but from habit, for lately I had risked myself only when it seemed profitable to our cause.

I was busy compartmenting-up my mind, finding instinct and reason as ever at strong war. Instinct said “Die,” but reason said that was only to cut the mind’s tether, and loose it into freedom: better to seek some mental death, some slow wasting of the brain to sink it below these puzzlements. An accident was meaner than deliberate fault. If I did not hesitate to risk my life, why fuss to dirty it? Yet life and honour seemed in different categories, not able to be sold one for another: and for honour, had I not lost that a year ago when I assured the Arabs that England kept her plighted word?

Or was honour like the Sybil’s leaves, the more that was lost the more precious the little left? Its part equal to the whole? My self-secrecy had left me no arbiter of responsibility. The debauch of physical work yet ended in a craving for more, while the everlasting doubt, the questioning, bound up my mind in a giddy spiral and left me never space for thought.

So we came at last, alive, to Jefer, where met us Feisal and Nuri in the smoothest spirits, with no mention of my price. It seemed incredible that this old man had freely joined our youth. For he was very old; livid, and worn, with a grey sorrow and remorse about him and a bitter smile the only mobility of his face. Upon his coarse eyelashes the eyelids sagged down in tired folds, through which, from the overhead sun, a red light glittered into his eye-sockets and made them look like fiery pits in which the man was slowly burning. Only the dead black of his dyed hair, only the dead skin of the face, with its net of lines, betrayed his seventy years.

There was ceremonial talk about this little-spoken leader, for with him were the head men of his tribe, famous sheikhs so bodied out with silks of their own wearing, or of Feisal’s gift, that they rustled like women while moving in slow state like oxen. First of them was Faris: like Hamlet, not forgiving Nuri his murdered father, Sottam: a lean man with drooping moustache, and white, unnatural face, who met the hidden censure of the world with a soft manner and luscious, deprecating voice. “Yifham,” he squeaked of me in astonishment. “He understands our Arabic.” Trad and Sultan were there, round-eyed, grave, and direct-spoken; honourable figures of men, and great leaders of cavalry. Also Mijhem, the rebellious, had been brought in by Feisal and reconciled with his unwilling uncle, who seemed only half to tolerate his small-featured bleak presence beside him, though Mijhem’s manner was eagerly friendly.

Mijhem was a great leader too, Trad’s rival in the conduct of raids, but weak and cruel at heart. He sat next Khalid, Trad’s brother, another healthy, cheerful rider, like Trad in face, but not so full a man. Durzi ibn Dughmi swelled in and welcomed me, reminding me ungratefully of his greediness at Nebk: a one-eyed, sinister, hook-nosed man; heavy, menacing and mean, but brave. There was the Khaffaji, the spoilt child of Nuri’s age, who looked for equality of friendliness from me, because of his father, and not for any promise in himself: he was young enough to be glad of the looming adventure of war and proud of his new bristling weapons.

Bender, the laughing boy, fellow in years and play with the Khaffaji, tripped me before them all by begging for a place in my bodyguard. He had heard from my Rahail, his foster-brother, of their immoderate griefs and joys, and servitude called to him with its unwholesome glamour. I fenced, and when he pleaded further, turned it by muttering that I was not a King to have Shaalan servants. Nuri’s sombre look met mine for a moment, in approval.

Beside me sat Rahail, peacocking his lusty self in strident clothes. Under cover of the conversation he whispered me the name of each chief. They had not to ask who I was, for my clothes and appearance were peculiar in the desert. It was notoriety to be the only clean-shaven one, and I doubled it by wearing always the suspect pure silk, of the whitest (at least outside), with a gold and crimson Meccan head-rope, and gold dagger. By so dressing I staked a claim which Feisal’s public consideration of me confirmed.

Many times in such councils had Feisal won over and set aflame new tribes, many times had the work fallen to me; but never until today had we been actively together in one company, reinforcing and relaying one another, from our opposite poles: and the work went like child’s play; the Rualla melted in our double heat. We could move them with a touch and a word. There was tenseness, a holding of breath, the glitter of belief in their thin eyes so fixed on us.

Feisal brought nationality to their minds in a phrase, which set them thinking of Arab history and language; then he dropped into silence for a moment: for with these illiterate masters of the tongue words were lively, and they liked to savour each, unmingled, on the palate. Another phrase showed them the spirit of Feisal, their fellow and leader, sacrificing everything for the national freedom; and then silence again, while they imagined him day and night in his tent, teaching, preaching, ordering and making friends: and they felt something of the idea behind this pictured man sitting there iconically, drained of desires, ambitions, weakness, faults; so rich a personality enslaved by an abstraction, made one-eyed, one armed, with the one sense and purpose, to live or die in its service.

Of course it was a picture-man; not flesh and blood, but nevertheless true, for his individuality had yielded its third dimension to the idea, had surrendered the world’s wealth and artifices. Feisal was hidden in his tent, veiled to remain our leader: while in reality he was nationality’s best servant, its tool, not its owner. Yet in the tented twilight nothing seemed more noble.

He went on to conjure up for them the trammelled enemy on the eternal defensive, whose best end was to have done no more than the necessary. While we abstinents swam calmly and coolly in the friendly silence of the desert, till pleased to come ashore.

Our conversation was cunningly directed to light trains of their buried thoughts; that the excitement might be their own and the conclusions native, not inserted by us. Soon we felt them kindle: we leaned back, watching them move and speak, and vivify each other with mutual heat, till the air was vibrant, and in stammered phrases they experienced the first heave and thrust of notions which ran up beyond their sight. They turned to hurry us, themselves the begetters, and we laggard strangers: strove to make us comprehend the full intensity of their belief; forgot us; flashed out the means and end of our desire. A new tribe was added to our comity: though Nuri’s plain “Yes” at the end carried more than all had said.

In our preaching there was nothing merely nervous. We did our best to exclude the senses, that our support might be slow, durable, unsentimental. We wanted no rice-converts. Persistently we did refuse to let our abundant and famous gold bring over those not spiritually convinced. The money was a confirmation; mortar, not building stone. To have bought men would have put our movement on the base of interest; whereas our followers must be ready to go all the way without other mixture in their motives than human frailty. Even I, the stranger, the godless fraud inspiring an alien nationality, felt a delivery from the hatred and eternal questioning of self in my imitation of their bondage to the idea; and this despite the lack of instinct in my own performance.

For naturally I could not long deceive myself; but my part was worked out so flippantly that none but Joyce, Nesib and Mohammed el Dheilan seemed to know I was acting. With man-instinctive, anything believed by two or three had a miraculous sanction to which individual ease and life might honestly be sacrificed. To man-rational, wars of nationality were as much a cheat as religious wars, and nothing was worth fighting for: nor could fighting, the act of fighting, hold any need of intrinsic virtue. Life was so deliberately private that no circumstances could justify one man in laying violent hands upon another’s: though a man’s own death was his last free will, a saving grace and measure of intolerable pain.

We made the Arabs strain on tiptoe to reach our creed, for it led to works, a dangerous country where men might take the deed for the will. My fault, my blindness of leadership (eager to find a quick means to conversion) allowed them this finite image of our end, which properly existed only in unending effort towards unattainable imagined light. Our crowd seeking light in things were like pathetic dogs snuffling round the shank of a lamppost. It was only myself who valeted the abstract, whose duty took him beyond the shrine.

The irony was in my loving objects before life or ideas; the incongruity in my answering the infectious call of action, which laid weight on the diversity of things. It was a hard task for me to straddle feeling and action. I had had one craving all my life—for the power of self-expression in some imaginative form—but had been too diffuse ever to acquire a technique. At last accident, with perverted humour, in casting me as a man of action had given me place in the Arab Revolt, a theme ready and epic to a direct eye and hand, thus offering me an outlet in literature, the technique-less art. Whereupon I became excited only over mechanism. The epic mode was alien to me, as to my generation. Memory gave me no clue to the heroic, so that I could not feel such men as Auda in myself. He seemed fantastic as the hills of Rumm, old as Mallory.

Among the Arabs I was the disillusioned, the sceptic, who envied their cheap belief. The unperceived sham looked so well-fitting and becoming a dress for shoddy man. The ignorant, the superficial, the deceived were the happy among us. By our swindle they were glorified. We paid for them our self-respect, and they gained the deepest feeling of their lives. The more we condemned and despised ourselves, the more we could cynically take pride in them, our creatures. It was so easy to overcredit others: so impossible to write down their motives to the level of our own uncharitable truth. They were our dupes, wholeheartedly fighting the enemy. They blew before our intentions like chaff, being not chaff, but the bravest, simplest and merriest of men. Credo quia sum? But did not the being believed by many make for a distorted righteousness? The mounting together of the devoted hopes of years from nearsighted multitudes, might endow even an unwilling idol with Godhead, and strengthen It whenever men prayed silently to Him.