LXXXIX

At dawn we went forward refreshed: but the weather had turned soft, with a greyness through which loomed the sad wormwood-covered hills. Upon their slopes the limestone ribs of this very old earth stood wearily exposed. In their hollows our difficulties increased with the mud. The misty valleys were sluggish streams of melting snow: and at last new thick showers of wet flakes began to fall. We reached the desolate ruins of Odroh in a midday like twilight: a wind was blowing and dying intermittently, and slow-moving banks of cloud and drizzle closed us about.

I bore right, to avoid the Beduin between us and Shobek: but our Howeitat companions led us straight upon their camp. We had ridden six miles in seven hours, and they were exhausted. The two Ateiba were not only exhausted, but demoralised, and swore mutinously that nothing in the world should keep us from the tribal tents. We wrangled by the roadside under the soft drift.

For myself I felt quite fresh and happy, averse from the delay of needless tribal hospitality. Zeid’s penniless state was excellent pretext for a trial of strength with the Edomite winter. Shobek was only ten miles further, and daylight had yet five hours to run. So I decided to go on alone. It would be quite safe, for in such weather neither Turk nor Arab was abroad, and the roads were mine. I took their four thousand pounds from Serj and Rameid, and cursed them into the valley for cowards: which really they were not. Rameid was catching his breath in great sobs, and Serj’s nervous pain marked each lurch of his camel with a running moan. They raved with miserable rage when I dismissed them and turned away.

The truth was that I had the best camel. The excellent Wodheiha struggled gamely forward under the weight of the extra gold. In flat places I rode her: at ascents and descents we used to slide together side by side with comic accidents, which she seemed rather to enjoy.

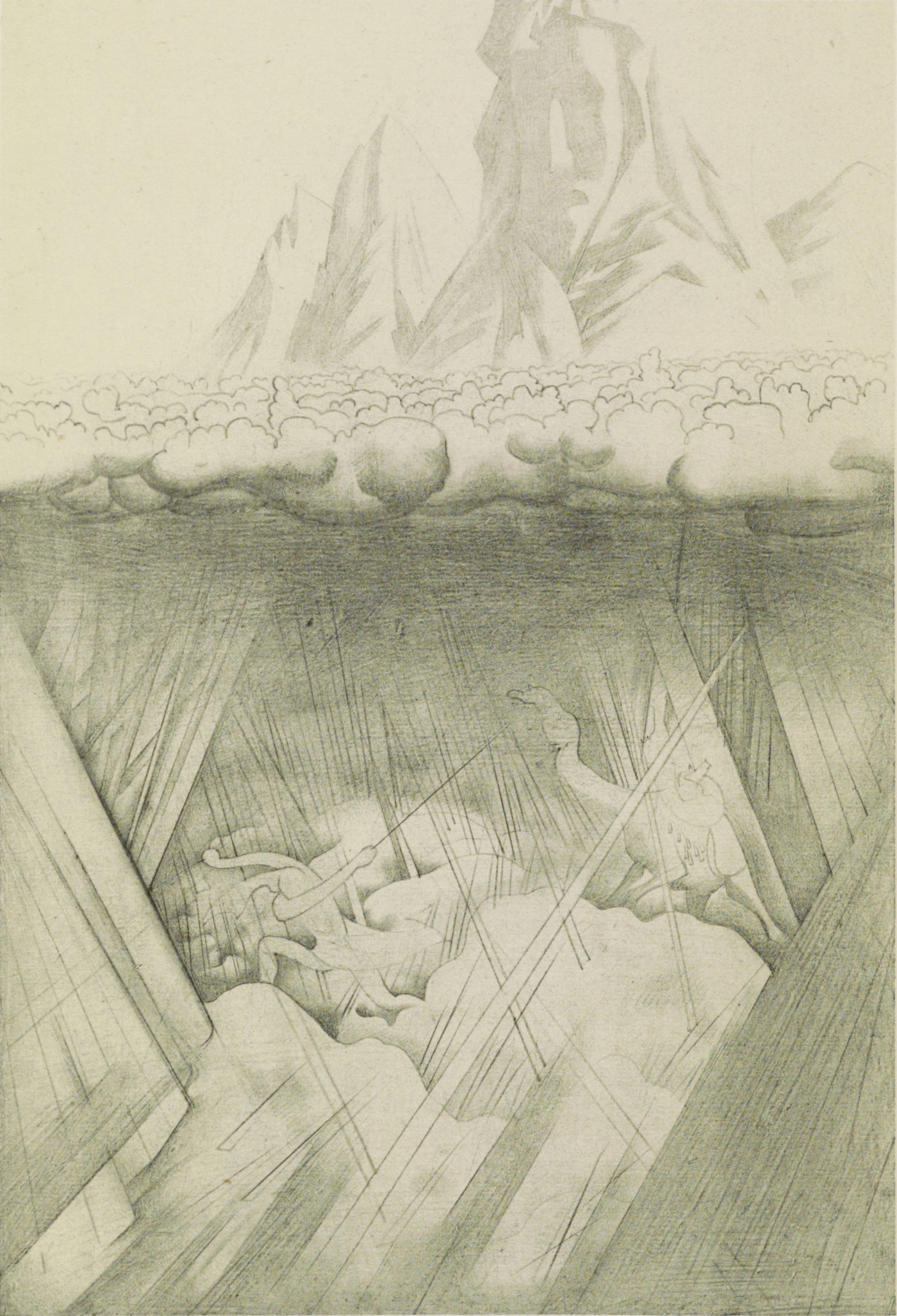

By sunset the snowfall ceased; we were coming down to the river of Shobek, and could see a brown track straggling over the opposite hill towards the village. I tried a shortcut, but the frozen crust of the mudbanks deceived me, and I crashed through the cat-ice (which was sharp, like knives) and bogged myself so deeply that I feared I was going to pass the night there, half in and half out of the sludge: or wholly in, which would be a tidier death.

Wodheiha, sensible beast, had refused to enter the morass: but she stood at a loss on the hard margin, and looked soberly at my mudlarking. However, I managed, with the still-held headstall, to persuade her a little nearer. Then I flung my body suddenly backward against the squelching quag, and, grabbing wildly behind my head, laid hold of her fetlock. She was frightened, and started back: and her purchase dragged me clear. We crawled farther down the bed to a safe place, and there crossed: after I had hesitatingly sat in the stream and washed off the weight of stinking clay.

Shiveringly I mounted again. We went over the ridge and down to the base of the shapely cone, whose mural crown was the ring-wall of the old castle of Monreale, very noble against the night sky. The chalk was hard, and it was freezing; snowdrifts lay a foot deep each side of the spiral path which wound up the hill. The white ice crackled desolately under my naked feet as we neared the gate, where, to make a stage entry, I climbed up by Wodheiha’s patient shoulder into the saddle. Then I repented, since only by throwing myself sideways along her neck did I avoid the voussoirs of the arch as she crashed underneath in half-terror of this strange place.

I knew that Sherif Abd el Main should be still at Shobek, so rode boldly up the silent street in the reeded starlight, which played with the white icicles and their underlying shadow among the walls and snowy roofs and ground. The camel stumbled doubtfully over steps hidden beneath a thick covering of snow: but I had no care of that, having reached my night’s goal, and having so powdery a blanket to fall on. At the crossways I called out the salutation of a fair night: and after a minute, a husky voice protested to God through the thick sacking which stuffed a loophole of the mean house on my right. I asked for Abd el Mayein, and was told “in the Government house” which lay at the further end of the old castle’s enceinte.

Arrived there I called again. A door was flung open, and a cloud of smoky light streamed recklessly across, whirling with motes, through which black faces peered to know who I was. I hailed them friendly, by name, saying that I was come to eat a sheep with the master: upon which these slaves ran out, noisy with astonishment, and relieved me of Wodheiha, whom they led into the reeking stable where themselves lived. One lit me with a flaming spar up the stone outside stairs to the house door, and between more servants, down a winding passage dripping with water from the broken roof, into a tiny room. There lay Abd el Muein upon a carpet, face down, breathing the least smoky level of air.

My legs were shaky, so I dropped beside him, and gladly copied his position to avoid the choking fumes of a brass brazier of flaming wood which crackled in a recessed shot-window of the mighty outer wall. He searched out for me a waistcloth, while I stripped off my things and hung them to steam before the fire, which became less smarting to the eyes and throat as it burned down into red coals. Meanwhile Abd el Mayin clapped his hands for supper to be hastened and served Fauzan (tea in Harith slang, so named from his cousin, governor of their village) hot and spiced and often, till the mutton, boiled with raisins in butter, was carried in.

He explained, with his blessings on the dish, that next day they would starve or rob, since he had here two hundred men, and no food or money, and his messengers to Feisal were held up in the snow. Whereat I, too, clapped hands, commanding my saddlebags, and presented him with five hundred pounds on account, till his subsidy came. This was good payment for the food, and we were very merry over my oddness of riding alone, in winter, with a hundredweight and more of gold for baggage. I repeated that Zeid, like himself, was straitened; and told of Serj and Rameid with the Arabs. The Sherif’s eyes darkened, and he made passes in the air with his riding stick. I explained, in extenuation of their failure, that the cold did not trouble me, since the English climate was of this sort most of the year. “God forbid it,” said Abd el Muyein.

After an hour he excused himself, because he had just married a Shobek wife. We talked of their marriage, whose end was the bearing of children: I withstood it, quoting old Dionysus of Tarsus.

At his sixty years without marriage they were shocked, holding procreation and evacuation alike as inevitable movements of the body; they repeated their half of the commandment to honour parents. I asked how they could look with pleasure on children, embodied proofs of their consummated lust? And invited them to picture the minds of the children, seeing crawl wormlike out of the mother that bloody, blinded thing which was themselves! It sounded to him a most excellent joke, and after it we rolled up in the rugs and slept warmly. The fleas were serried, but my nakedness, the Arab defence against a verminous bed, lessened their plague: and the bruises did not prevail because I was too tired.

In the morning I rose with a splitting headache, and said I must go on. Two men were found to ride with me, though all said we should not reach Tafileh that night. However, I thought it could not be worse than yesterday; so we skated timorously down the rapid path to the plain across which still stretched the Roman road with its groups of fallen milestones, inscribed by famous emperors.

From this plain the two faint-hearts with me slipped back to their fellows on the castle-hill. I proceeded, alternately on and off my camel, like the day before, though now the way was all too slippery, except on the ancient paving, the last footprint of Imperial Rome which had once, so much more preciously, played the Turk to the desert dwellers. On it I could ride: but I had to walk and wade the dips where the floods of fourteen centuries had washed the road’s foundations out. Rain came on, and soaked me, and then it blew fine and freezing till I crackled in armour of white silk, like a theatre knight: or like a bridal cake, hard iced.

The camel and I were over the plain in three hours; wonderful going: but our troubles were not ended. The snow was indeed as my guides had said, and completely hid the path, which wound uphill between walls and ditches, and confused piles of stone. It cost me an infinity of pain to turn the first two corners. Wodheiha, tired of wading to her bony knees in useless white stuff, began perceptibly to flag. However, she got up one more steep bit, only to miss the edge of the path in a banked place. We fell together some eighteen feet down the hillside into a yard-deep drift of frozen snow. After the fall she rose to her feet whimpering and stood still, in a tremble.

When he-camels so baulked, they would die on their spot, after days; and I feared that now I had found the limit of effort in she-camels. I plunged to my neck in front of her, and tried to tow her out, vainly. Then I spent a long time hitting her behind. I mounted, and she sat down. I jumped off, heaved her up, and wondered if, perhaps, it was that the drift was too thick. So I carved her a beautiful little road, a foot wide, three deep, and eighteen paces long, using my bare feet and hands as tools. The snow was so frozen on the surface that it took all my weight first to break it down, and then to scoop it out. The crust was sharp, and cut my wrists and ankles till they bled freely, and the roadside became lined with pink crystals, looking like pale, very pale, watermelon flesh.

Afterwards I went back to Wodheiha, patiently standing there, and climbed into the saddle. She started easily. We went running at it, and such was her speed that the rush carried her right over the shallow stuff, back to the proper road. Up this we went cautiously, with me, afoot, sounding the path in front with my stick, or digging new passes when the drifts were deep. In three hours we were on the summit, and found it windswept on the western side. So we left the track, and scrambled unsteadily along the very broken crest, looking down across the chessboard houses of Dana village, into sunny Arabah, fresh and green, thousands of feet below.

When the ridge served no more we did further heavy work, and at last Wodheiha baulked again. It was getting serious, for the evening was near; suddenly I realised the loneliness, and that if the night found us yet beyond help on this hilltop, Wodheiha would die, and she was a very noble beast. There was also the solid weight of gold, and I felt not sure how far, even in Arabia, I could safely put six thousand sovereigns by the roadside with a signet as mark of ownership, and leave them for a night. So I took her back a hundred yards along our beaten track, mounted, and charged her at the bank. She responded. We burst through and over the northern lip which looked down on the Senussi village of Rasheidiya.

This face of the hill, sheltered from the wind and open to the sun all afternoon, had thawed. Underneath the superficial snow lay wet and muddy ground; and when Wodheiha ran upon this at speed her feet went from under her and she sprawled, with her four feet locked. So on her tail, with me yet in the saddle, we went sliding round and down a hundred feet. Perhaps it hurt the tail (there were stones under the snow) for on the level she sprang up unsteadily, grunting, and lashed it about like a scorpion’s. Then she began to run at ten miles an hour down the greasy path towards Rasheidiya, sliding and plunging wildly: with me, in terror of a fall and broken bones, clinging to the horns of the saddle.

A crowd of Arabs, Zeid’s men, weather-bound here on their way to Feysal, ran out when they heard her trumpeting approach, and shouted with joy at so distinguished an entry to the village. I asked them the news; they told me all was well. Then I remounted, for the last eight miles into Tafileh, where I gave Zeid his letters and some money, and went gladly to bed … flea-proof for another night.