LXXXIV

Remote from the fighting line, in Akaba, during this pause we saw the reverse of the shield, the corruption of our enthusiasm, which made the moral condition of the base unsatisfactory. We rejoiced when at last we were able to escape into the clean, fresh hills about Guweira. The early winter gave us days hot and sunny, or days overcast, with clouds massed about the head of the plateau nine miles away, where Maulud was keeping his watch in the mist and rain. The evenings held just enough of chill to add delightful value to a thick cloak and a fire.

We waited in Guweira for news of the opening of our operation against Tafileh, the knot of villages commanding the south end of the Dead Sea. We planned to tackle it from west, south, and east, at once; the east opening the ball by attacking Jurf, its nearest station on the Hejaz line. Conduct of this attack had been trusted to Sherif Nasir, the Fortunate. With him went Nuri Said, Jaafar’s chief of staff, commanding some regulars, a gun, and some machine-guns. They were working from Jefer. After three days their post came in. As usual Nasir had directed his raid with skill and deliberation. Jurf, the objective, was a strong station of three stone buildings with outer-works and trenches. Behind the station was a low mound, trenched and walled, on which the Turks had set two machine-guns and a mountain-gun. Beyond the mound lay a high, sharp ridge, the last spur of the hills which divided Jefer from Bair.

The weakness of the defence lay in this ridge, for the Turks were too few to hold both it and the knoll or station, and its crest overlooked the railway. Nasir one night occupied the whole top of the hill without alarm, and then cut the line above and below the station. A few minutes later, when it was light enough to see, Nuri Said brought his mountain-gun to the edge of the ridge; and, with a third lucky shot, a direct hit, silenced the Turkish gun beneath his view.

Nasir grew greatly excited: the Beni Sakhr mounted their camels, swearing they would charge in forthwith. Nuri thought it madness while Turkish machine-guns were still in action from trenches: but his words had no effect upon the Bedu. In desperation he opened a rattling fire with all he had against the Turkish position, and the Beni Sakhr swept round the foot of the main ridge and up over the knoll in a flash. When they saw this camel-horde racing at them, the Turks flung away their rifles and fled into the station. Only two Arabs were fatally hurt.

Nuri ran down to the knoll. The Turkish gun was undamaged. He slewed it round and discharged it point blank into the ticket office. The Beni Sakhr mob yelled with joy to see the wood and stones flying, jumped again on their camels and loped into the station just as the enemy surrendered. Nearly two hundred Turks, including seven officers, survived as our prisoners.

The Bedu became rich: besides the weapons, there were twenty-five mules, and in the siding seven trucks of delicacies for the officers’ messes of Medina. There were things the tribesmen had only heard of, and things they had never heard of: they were supremely happy. Even the unfortunate regulars got a share, and were able once more to enjoy olives, sesame paste, dried apricot, and other sweet or pickled products of their native, half-forgotten, Syria.

Nuri Said had artificial tastes, and rescued tinned meats and liquors from the wilder men. There was one whole truck of tobacco. As the Howeitat did not smoke, it was divided between the Beni Sakhr and the regulars. By its loss the Medina garrison became tobacco-less: their sad plight later so worked on Feisal, a confirmed smoker, that he loaded some pack-camels with cheap cigarettes and drove them into Tebuk with his compliments.

After the looting, the engineers fired charges under the two engines, against the water tower, in the pump, and between the points of the sidings. They burned the captured trucks and damaged a bridge; but perfunctorily, for, as usual after victory, everyone was too loaded and too hot to care for altruistic labour. They camped behind the station, and about midnight had an alarm, when the noise and lights of a train came from the south and halted, clearly with foreknowledge, by the break of the evening before. Auda sent scouts to report.

Before they had returned a solitary sergeant walked into Nasir’s camp as a volunteer for the Sherif’s army. He had been sent out by the Turks to explore the station. His story was that there were only sixty men and a mountain-gun on the relief train, which, if he went back with smooth news, might be surprised without a shot fired. Nasir called Auda, who called the Howeitat, and they went off silently to lay the trap: but just before they got there our scouts decided to do their unaided best, and opened fire against the coaches. In fear, the engine reversed, and rolled the train back, unhurt, to Maan. It was the only sorrow of Jurf.

After this raid the weather once more broke. For three successive days came falls of snow. Nasir’s force with difficulty regained the tents at Jefer. This plateau about Maan lay between three and five thousand feet above sea level, open to all winds from north and east. They blew from Central Asia, or from Caucasus, terribly over the great desert to these low hills of Edom, against which their first fury broke. The surplus bitterness lipped the crest and made a winter, quite severe of its degree, below in Judaea and Sinai.

Outside Beersheba and Jerusalem the British found it cold; but our Arabs fled there to get warm. Unhappily the British supply staff realised too late that we were fighting in a little Alp. They would not give us tents for one-quarter of our troops, nor serge clothing, nor boots, nor blankets enough to issue two to each man of the mountain garrisons. Our soldiers, if they neither deserted nor died, existed in an aching misery which froze the hope out of them.

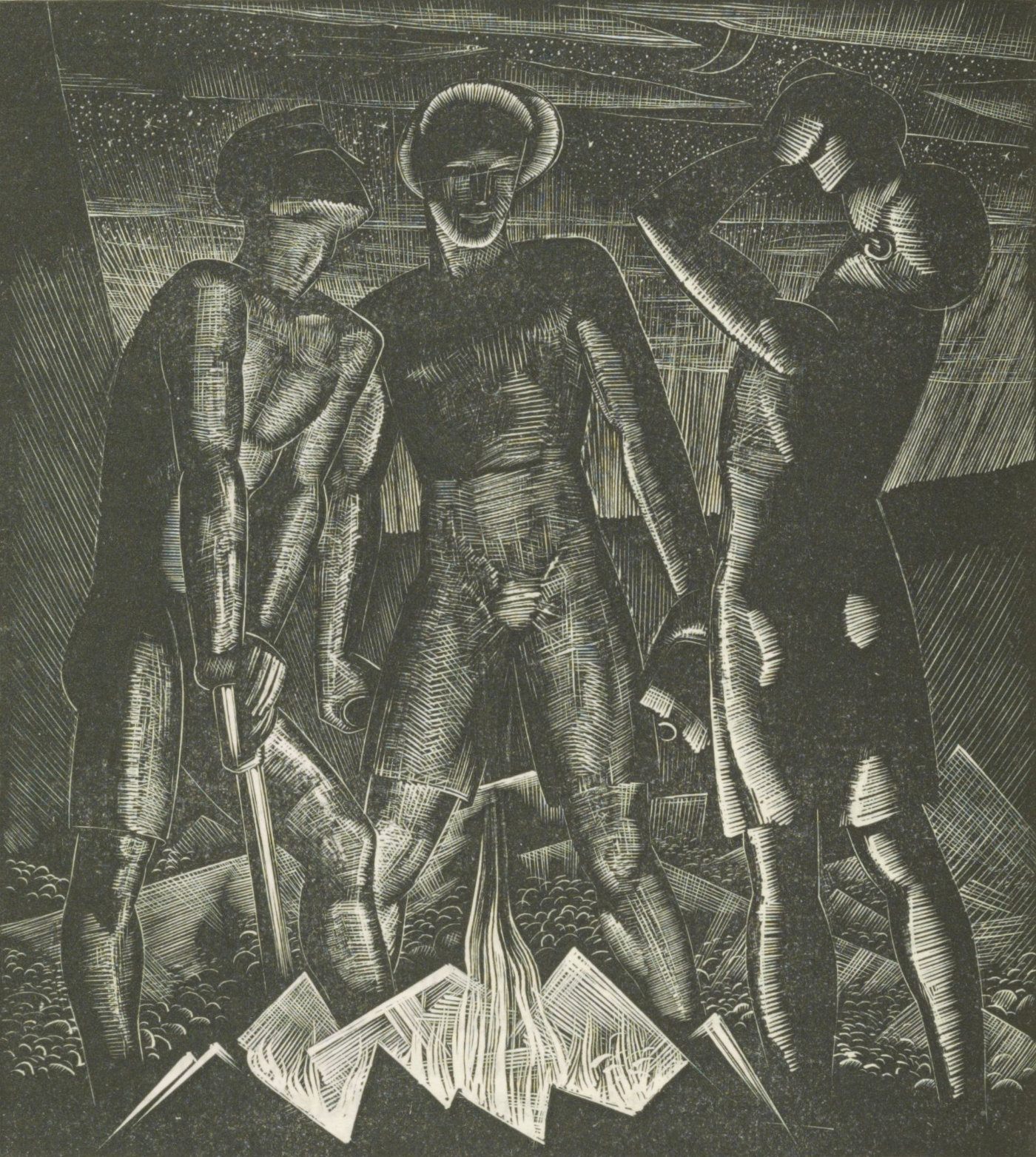

According to our plan the good news of Jurf was to send the Arabs of Petra, under Sherif Abd el Mayin, at once up their hills into the forest towards Shobek. It was an uncanny march in the hoar mist, that of these frozen-footed peasants in their sheepskins, up and down sharp valleys and dangerous hillsides, out of whose snowdrifts the heavy trunks of junipers, grudging in leaves, jutted like castings in grey iron. The ice and frost broke down the animals, and many of the men; yet these hardy highlanders, used to being too cold throughout their winter, persisted in the advance.

The Turks heard of them as they struggled slowly nearer, and fled from the caves and shelters among the trees to the branch railhead, littering the roads of their panic with cast baggage and equipment.

Railhead of the forest railway, with its temporary sheds, was commanded from low ridges by the Arab gunfire, and no better than a trap. The tribesmen, in a pack, tore the enemy to pieces as they ran out from their burning and falling walls. One disciplined company of proper troops, under an Albanian officer, fought their way to the main line; but the Arabs killed or took the others, and also the stores in Shobek, the old Crusader fort of Monreale, poised high on a chalk cone above its winding valley. Abd el Mayein put his headquarters there, and sent word to Nasir. Mastur, too, was told. He drew his Motalga horse and foot from the comfort of their tents in the sunny depths of Arabia and with them climbed the hill-pass eastward towards Tafileh.

However, the advantage lay with Nasir, who leaped in one day from Jefer, and after a whirlwind night appeared at dawn on the rocky brink of the ravine in which Tafileh hid, and summoned it to surrender on pain of bombardment: an idle threat, for Nuri Said with the guns had gone back to Guweira. There were only one hundred and eighty Turks in the village, but they had supporters in the Muhaisin, a clan of the peasantry; not for love so much as because Dhiab, the vulgar headman of another faction, had declared for Feisal. So they shot up at Nasir a stream of ill-directed bullets.

The Howeitat spread out along the cliffs to return the peasants’ fire. This manner of going displeased Auda, the old lion, who raged that a mercenary village folk should dare to resist their secular masters, the Abu Tayi. So he jerked his halter, cantered his mare down the path, and rode out plain to view beneath the easternmost houses of the village. There he reined in, and shook a hand at them, booming in his wonderful voice: “Dogs, do you not know Auda?” When they realised it was that implacable son of war their hearts failed them, and an hour later Sherif Nasir in the town-house was sipping tea with his guest the Turkish Governor, trying to console him for the sudden change of fortune.

At dark Mastur rode in. His Motalga looked blackly at their blood enemies the Abu Tayi, lolling in the best houses. The two Sherifs divided up the place, to keep their unruly followers apart. They had little authority to mediate, for by passage of time Nasir was nearly adopted into the Abu Tayi, and Mastur into the Jazi.

When morning came the factions were bickering; and the day passed anxiously; for besides these blood enemies, the Muhaisin were fighting for authority among the villagers, and further complications developed in two stranger elements: one a colony of free-booting Senussi from North Africa, who had been intruded by the Turks into some rich, but half-derelict plough-land; the other a plaintive, and active, suburb of a thousand Armenians, survivors of an infamous deportation by the Young Turks in 1915.

The people of Tafileh went in deadly fear of the future. We were, as usual, short of food and short of transport, and they would remedy neither ill. They had wheat or barley in their bins; but hid it. They had pack-animals, asses and mules, in abundance; but drove them away for safety. They could have driven us away too, but were, fortunately for us, short of the sticking point. Incuriousness was the most potent ally of our imposed order; for Eastern government rested not so much on consent or force, as on the common supinity, hebetude, lack-a-daisiness, which gave a minority undue effect.

Feisal had delegated command of this push towards the Dead Sea to his young half-brother Zeid. It was Zeid’s first office in the north, and he set out eager with hope. As adviser he had Jaafar Pasha, our general. His infantry, gunners and machine-gunners stuck, for lack of food, at Petra; but Zeid himself and Jaafar rode on to Tafileh.

Things were almost at a break. Auda affected a magnanimity very galling to the Motalga boys, Metaab and Annad, sons of Abtan, whom Auda’s son had killed. They, lithe, definite, self-conscious figures, began to talk big about revenge—tomtits threatening a hawk. Auda declared he would whip them in the marketplace if they were rude. This was very well, but their followers were two to every man of his, and we should have the village in a blaze. The young fellows, with Rahail, my ruffler, went flaunting in every street.

Zeid thanked and paid Auda, and sent him back to his desert. The enlightened heads of the Muhaisin had to go as forced guests to Feisal’s tent. Dhiab, their enemy, was our friend: we remembered regretfully the adage that the best allies of a violently-successful new regime were not its partisans, but its opponents. By Zeid’s plenty of gold the economic situation improved. We appointed an officer-governor and organised our five villages for further attack.