LIV

Meanwhile our Arabs had plundered the Turks, their baggage train, and their camp; and soon after moonrise, Auda came to us and said that we must move. It angered Nasir and myself. Tonight there was a dewy west wind blowing, and at Aba el Lissan’s four thousand feet, after the heat and burning passion of the day, its damp chill struck very sharply on our wounds and bruises. The spring itself was a thread of silvery water in a runnel of pebbles across delightful turf, green and soft, on which we lay, wrapped in our cloaks, wondering if something to eat were worth preparing: for we were subject at the moment to the physical shame of success, a reaction of victory, when it became clear that nothing was worth doing, and that nothing worthy had been done.

Auda insisted. Partly it was superstition—he feared the newly-dead around us; partly lest the Turks return in force; partly lest other clans of the Howeitat take us, lying there broken and asleep. Some were his blood enemies: others might say they came to help our battle, and in the darkness thought we were Turks and fired blindly. So we roused ourselves, and jogged the sorry prisoners into line.

Most had to walk. Some twenty camels were dead or dying from wounds which they had got in the charge, and others were over weak to take a double burden. The rest were loaded with an Arab and a Turk; but some of the Turkish wounded were too hurt to hold themselves on pillion. In the end we had to leave about twenty on the thick grass beside the rivulet, where at least they would not die of thirst, though there was little hope of life or rescue for them.

Nasir set himself to beg blankets for these abandoned men, who were half-naked; and while the Arabs packed, I went off down the valley where the fight had been, to see if the dead had any clothing they could spare. But the Beduin had been beforehand with me, and had stripped them to the skin. Such was their point of honour.

To an Arab an essential part of the triumph of victory was to wear the clothes of an enemy: and next day we saw our force transformed (as to the upper half) into a Turkish force, each man in a soldier’s tunic: for this was a battalion straight from home, very well found and dressed in new uniforms.

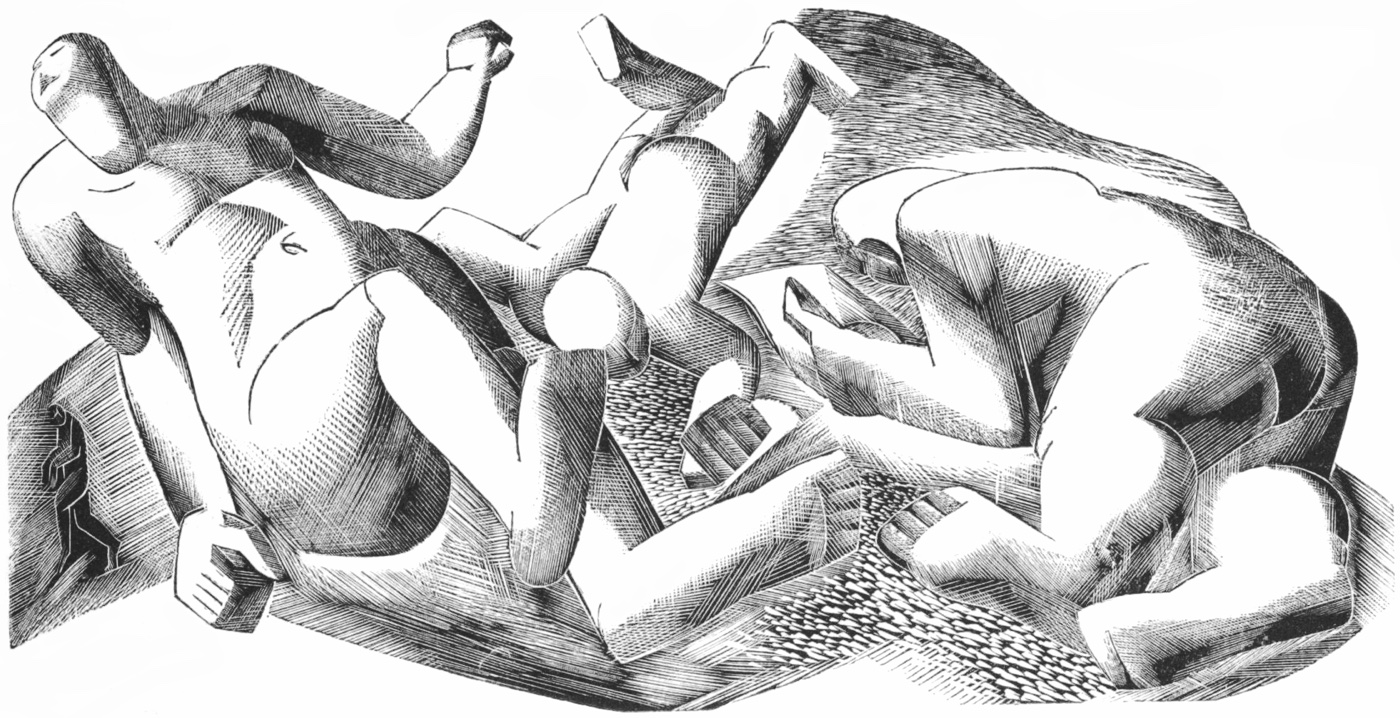

The dead men looked wonderfully beautiful. The night was shining gently down, softening them into new ivory. Turks were white-skinned on their clothed parts, much whiter than the Arabs; and these soldiers had been very young. Close round them lapped the dark wormwood, now heavy with dew, in which the ends of the moonbeams sparkled like sea-spray. The corpses seemed flung so pitifully on the ground, huddled anyhow in low heaps. Surely if straightened they would be comfortable at last. So I put them all in order, one by one, very wearied myself, and longing to be of these quiet ones, not of the restless, noisy, aching mob up the valley, quarrelling over the plunder, boasting of their speed and strength to endure God knew how many toils and pains of this sort; with death, whether we won or lost, waiting to end the history.

In the end our little army was ready, and wound slowly up the height and beyond into a hollow sheltered from the wind; and there, while the tired men slept, we dictated letters to the Sheikhs of the coastal Howeitat, telling them of the victory, that they might invest their nearest Turks, and hold them till we came. We had been kind to one of the captured officers, a policeman despised by his regular colleagues, and him we persuaded to be our Turkish scribe to the commandants of Guweira, Kethera, and Hadra, the three posts between us and Akaba, telling them that if our blood was not hot we took prisoners, and that prompt surrender would ensure their good treatment and safe delivery to Egypt.

This lasted till dawn, and then Auda marshalled us for the road, and led us up the last mile of soft heath-clad valley between the rounded hills. It was intimate and homelike till the last green bank; when suddenly we realised it was the last, and beyond lay nothing but clear air. The lovely change this time checked me with amazement; and afterwards, however often we came, there was always a catch of eagerness in the mind, a pricking forward of the camel and straightening up to see again over the crest into openness.

Shtar hillside swooped away below us for hundreds and hundreds of feet, in curves like bastions, against which summer-morning clouds were breaking: and from its foot opened the new earth of the Guweira plain. Aba el Lissan’s rounded limestone breasts were covered with soil and heath, green, well watered. Guweira was a map of pink sand, brushed over with streaks of watercourses, in a mantle of scrub: and, out of this, and bounding this, towered islands and cliffs of glowing sandstone, wind-scarped and rain-furrowed, tinted celestially by the early sun.

After days of travel on the plateau in prison valleys, to meet this brink of freedom was a rewarding vision, like a window in the wall of life. We walked down the whole zigzag pass of Shtar, to feel its excellence, for on our camels we rocked too much with sleep to dare see anything. At the bottom the animals found a matted thorn which gave their jaws pleasure; we in front made a halt, rolled on to sand soft as a couch, and incontinently slept.

Auda came. We pleaded that it was for mercy upon our broken prisoners. He replied that they alone would die of exhaustion if we rode, but if we dallied, both parties might die: for truly there was now little water and no food. However, we could not help it, and stopped that night short of Guweira, after only fifteen miles. At Guweira lay Sheikh ibn Jad, balancing his policy to come down with the stronger: and today we were the stronger, and the old fox was ours. He met us with honeyed speeches. The hundred and twenty Turks of the garrison were his prisoners; we agreed with him to carry them at his leisure and their ease to Akaba.

Today was the fourth of July. Time pressed us, for we were hungry, and Akaba was still far ahead behind two defences. The nearer post, Kethira, stubbornly refused parley with our flags. Their cliff commanded the valley—a strong place which it might be costly to take. We assigned the honour, in irony, to ibn Jad and his unwearied men, advising him to try it after dark. He shrank, made difficulties, pleaded the full moon: but we cut hardly into this excuse, promising that tonight for a while there should be no moon. By my diary there was an eclipse. Duly it came, and the Arabs forced the post without loss, while the superstitious soldiers were firing rifles and clanging copper pots to rescue the threatened satellite.

Reassured we set out across the strandlike plain. Niazi Bey, the Turkish battalion commander, was Nasir’s guest, to spare him the humiliation of Beduin contempt. Now he sidled up by me, and, his swollen eyelids and long nose betraying the moroseness of the man, began to complain that an Arab had insulted him with a gross Turkish word. I apologised, pointing out that it must have been learnt from the mouth of one of his Turkish fellow-governors. The Arab was repaying Caesar.

Caesar, not satisfied, pulled from his pocket a wizened hunch of bread to ask if it was fit breakfast for a Turkish officer. My heavenly twins, foraging in Guweira, had bought, found, or stolen a Turkish soldier’s ration loaf; and we had quartered it. I said it was not breakfast, but lunch and dinner, and perhaps tomorrow’s meals as well. I, a staff officer of the British Army (not less well fed than the Turkish), had eaten mine with the relish of victory. It was defeat, not bread, which stuck in his gullet, and I begged him not to blame me for the issue of a battle imposed on both our honours.

The narrows of Wadi Itm increased in intricate ruggedness as we penetrated deeper. Below Kethira we found Turkish post after Turkish post, empty. Their men had been drawn in to Khadra, the entrenched position (at the mouth of Itm), which covered Akaba so well against a landing from the sea. Unfortunately for them the enemy had never imagined attack from the interior, and of all their great works not one trench or post faced inland. Our advance from so new a direction threw them into panic.

In the afternoon we were in contact with this main position, and heard from the local Arabs that the subsidiary posts about Akaba had been called in or reduced, so that only a last three hundred men barred us from the sea. We dismounted for a council, to hear that the enemy were resisting firmly, in bombproof trenches with a new artesian well. Only it was rumoured that they had little food.

No more had we. It was a deadlock. Our council swayed this way and that. Arguments bickered between the prudent and the bold. Tempers were short and bodies restless in the incandescent gorge whose granite peaks radiated the sun in a myriad shimmering points of light, and into the depths of whose tortuous bed no wind could come to relieve the slow saturation of the air with heat.

Our numbers had swollen double. So thickly did the men crowd in the narrow space, and press about us, that we broke up our council twice or thrice, partly because it was not good they should overhear us wrangling, partly because in the sweltering confinement our unwashed smells offended us. Through our heads the heavy pulses throbbed like clocks.

We sent the Turks summonses, first by white flag, and then by Turkish prisoners, but they shot at both. This inflamed our Beduin, and while we were yet deliberating a sudden wave of them burst up on to the rocks and sent a hail of bullets spattering against the enemy. Nasir ran out barefoot, to stop them, but after ten steps on the burning ground screeched for sandals; while I crouched in my atom of shadow, too wearied of these men (whose minds all wore my livery) to care who regulated their febrile impulses.

However, Nasir prevailed easily. Farraj and Daud had been ringleaders. For correction they were set on scorching rocks till they should beg pardon. Daud yielded immediately; but Farraj, who, for all his soft form, was of whipcord and much the master-spirit of the two, laughed from his first rock, sat out the second sullenly, and gave way with a bad grace only when ordered to a third.

His stubbornness should have been stringently visited: but the only punishment possible to our hands in this vagrant life was corporal, which had been tried upon the pair so often and so uselessly that I was sick of it. If confined this side of cruelty the surface pain seemed only to irritate their muscles into activities wilder than those for which they had been condemned. Their sins were elvish gaiety, the thoughtlessness of unbalanced youth, the being happy when we were not; and for such follies to hurt them mercilessly like criminals till their self-control melted and their manhood was lost under the animal distress of their bodies, seemed to me degrading, almost an impiety towards two sunlit beings, on whom the shadow of the world had not yet fallen—the most gallant, the most enviable, I knew.

We had a third try to communicate with the Turks, by means of a little conscript, who said that he understood how to do it. He undressed, and went down the valley in little more than boots. An hour later he proudly brought us a reply, very polite, saying that in two days, if help did not come from Maan, they would surrender.

Such folly (for we could not hold our men indefinitely) might mean the massacre of every Turk. I held no great brief for them, but it was better they be not killed, if only to spare us the pain of seeing it. Besides, we might have suffered loss. Night operations in the staring moon would be nearly as exposed as day. Nor was this, like Aba el Lissan, an imperative battle.

We gave our little man a sovereign as earnest of reward, walked down close to the trenches with him, and sent in for an officer to speak with us. After some hesitation this was achieved, and we explained the situation on the road behind us; our growing forces; and our short control over their tempers. The upshot was that they promised to surrender at daylight. So we had another sleep (an event rare enough to chronicle) in spite of our thirst.

Next day at dawn fighting broke out on all sides, for hundreds more hill-men, again doubling our number, had come in the night; and, not knowing the arrangement, began shooting at the Turks, who defended themselves. Nasir went out, with ibn Dgheithir and his Ageyl marching in fours, down the open bed of the valley. Our men ceased fire. The Turks then stopped, for their rank and file had no more fight in them and no more food, and thought we were well supplied. So the surrender went off quietly after all.

As the Arabs rushed in to plunder I noticed an engineer in grey uniform, with red beard and puzzled blue eyes; and spoke to him in German. He was the well-borer, and knew no Turkish. Recent doings had amazed him, and he begged me to explain what we meant. I said that we were a rebellion of the Arabs against the Turks. This, it took him time to appreciate. He wanted to know who was our leader. I said the Sherif of Mecca. He supposed he would be sent to Mecca. I said rather to Egypt. He inquired the price of sugar, and when I replied, “cheap and plentiful,” he was glad.

The loss of his belongings he took philosophically, but was sorry for the well, which a little work would have finished as his monument. He showed me where it was, with the pump only half-built. By pulling on the sludge bucket we drew enough delicious clear water to quench our thirsts. Then we raced through a driving sandstorm down to Akaba, four miles further, and splashed into the sea on July the sixth, just two months after our setting out from Wejh.