LII

Nasir had done great work. A week’s flour for us had come from Tafileh, to restore our freedom of movement. We might well take Akaba before we starved again. He had good letters from the Dhumaniyeh, the Darausha, and the Dhiabat, three Howeitat clans on Nagb el Shtar, the first difficult pass of the Maan-Akaba road. They were willing to help us, and if they struck soon and strongly at Aba el Lissan the great factor of surprise would probably mean success to their effort.

My hopefulness misled me into another mad ride, which miscarried. Yet the Turks did not take alarm. As my party rode in there came a messenger posthaste from Nuri Shaalan. He brought greetings, and Nuri’s news that the Turks had called upon his son Nawaf, as guide-hostage, to take four hundred cavalry from Deraa down the Sirhan in search of us. Nuri had sent his better-spared nephew Trad, who was conducting them by devious routes in which men and horses were suffering terribly from thirst. They were near Nebk, our old camping ground. The Turkish Government would believe us still in the Wadi till their cavalry returned. For Maan especially they had no anxiety since the engineers who had blown up Bair reported every source of water utterly destroyed, while the wells of Jefer had been dealt with a few days earlier.

It might be that Jefer really was denied to us; but we were not without hope that there too we should find the technical work of demolition ill-done by these pitiful Turks. Dhaif-Allah, a leading man of the Jazi Howeitat, one who came down to Wejh and swore allegiance, had been present in Jefer when the King’s Well was fired by dynamite placed about its lip; and sent us secret word from Maan that he had heard the upper stones clap together and key over the mouth of the well. His conviction was that the shaft was intact, and the clearing of it a few hours’ work. We hoped so; and rode away from Bair all in order, on the twenty-eighth of June, to find out.

Quickly we crossed the weird plain of Jefer. Next day by noon we were at the wells. They seemed most thoroughly destroyed; and the fear grew that we might find in them the first check to our scheme of operations, a scheme so much too elaborate that a check might be far reaching.

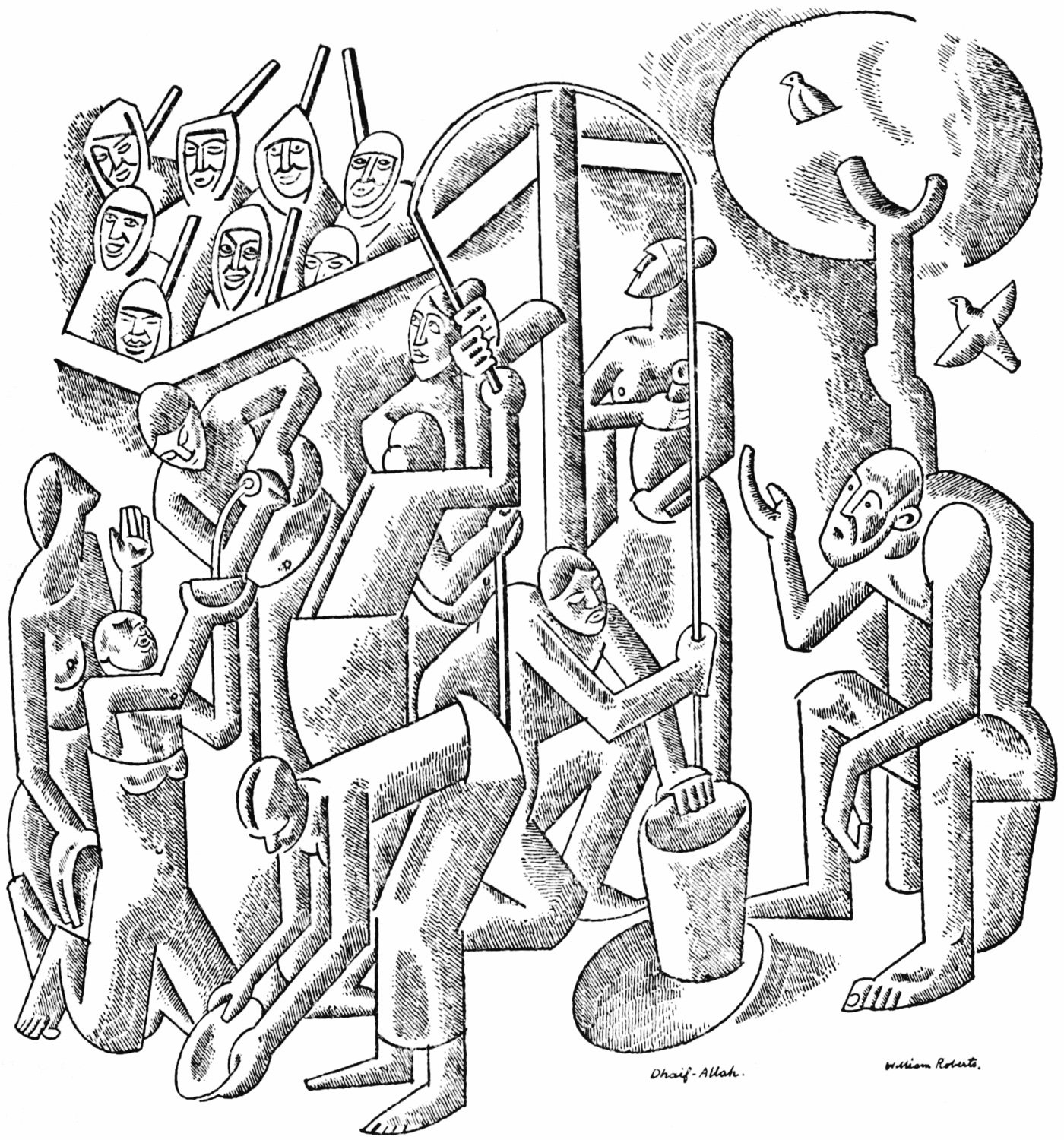

However, we went to the well—Auda’s family property—of which Dhaif Allah had told us the tale, and began to sound about it. The ground rang hollow under our mallet, and we called for volunteers able to dig and build. Some of the Ageyl came forward, led by the Mirzugi, a capable camel boy of Nasir’s. They started with the few tools we had. The rest of us formed a ring round the well-depression and watched them work, singing to them and promising rewards of gold when they had found the water.

It was a hot task in the full glare of the summer sun; for the Jefer plain was of hard mud, flat as the hand, blinding white with salt, and twenty miles across; but time pressed, because if we failed we might have to ride fifty miles in the night to the next well. So we pushed the work by relays at speed through the midday heat, turning into labourers all our amenable fellows. It made easy digging, for the explosion which shifted the stones had loosened the soil.

As they dug and threw out the earth, the core of the well rose up like a tower of rough stones in the centre of the pit. Very carefully we began to take away the ruined head of the pile: difficult work, for the stones had become interlocked in their fall; but this was the better sign, and our spirits rose. Before sunset the workers shouted that there was no more packing-soil, that the interstices between the blocks were clear, and they heard the mud fragments which slipped through splashing many feet below.

Half an hour later came a rush and rumble of stones in the mouth, followed by a heavy splash and yells. We hurried down, and by the Mirzugi’s torch saw the well yawning open, no longer a tube, but a deep bottle-shouldered pit, twenty feet across at the bottom, which was black with water and white in the middle with spray where the Ageyli who had been clearing when the key slipped, was striking out lustily in the effort not to drown. Everybody laughed down the well at him, till at last Abdulla lowered him a noose of rope, and we drew him up, very wet and angry, but in no way damaged by his fall.

We rewarded the diggers, and feasted them on a weak camel, which had failed in the march today; and then all night we watered, while a squad of Ageyl, with a long chorus, steyned up to ground level an eight-foot throat of mud and stones. At dawn the earth was stamped in round this, and the well stood complete, as fit in appearance as ever. Only the water was not very much. We worked it the twenty-four hours without rest, and ran it to a cream; and still some of our camels were not satisfied.

From Jefer we took action. Riders went forward into the Dhumaniyeh tents to lead their promised attack against Fuweilah, the blockhouse which covered the head of the pass of Aba el Lissan. Our attack was planned for two days before the weekly caravan which, from Maan, replenished the client garrisons. Starvation would make reduction of these distant places easier, by impressing on them how hopelessly they were cut off from their friends.

We sat in Jefer meanwhile, waiting to hear the fortune of the attack. On its success or failure would depend the direction of our next march. The halt was not unpleasant, for our position had its comic side. We were within sight of Maan, during those minutes of the day in which the mirage did not make eyes and glasses useless; and yet we strolled about admiring our new well-lip in complete security, because the Turkish garrison believed water impossible here or at Bair, and were hugging the pleasant idea that we were now desperately engaged with their cavalry in Sirhan.

I hid under some bushes near the well for hours, against the heat, very lazy, pretending to be asleep, the wide silk sleeve of my pillow-arm drawn over my face as veil against the flies. Auda sat up and talked like a river, telling his best stories in great form. At last I reproved him with a smile, for talking too much and doing too little. He sucked his lips with pleasure of the work to come.

In the following dawn a tired horseman rode into our camp with news that the Dhumaniyeh had fired on the Fuweilah post the afternoon before as soon as our men had reached them. The surprise had not been quite complete; the Turks manned their dry stone breastworks and drove them off. The crestfallen Arabs drew back into cover, and the enemy, believing it only an ordinary tribal affray had made a mounted sortie upon the nearest encampment.

One old man, six women and seven children were its only occupants. In their anger at finding nothing actively hostile or able-bodied, the troopers smashed up the camp and cut the throats of its helpless ones. The Dhumaniyeh on the hilltops heard and saw nothing till it was too late; but then, in their fury, they dashed down across the return road of the murderers and cut them off almost to the last man. To complete their vengeance they assaulted the now weakly-garrisoned fort, carried it in the first fierceness of their rush, and took no prisoners.

We were ready saddled; and within ten minutes had loaded and marched for Ghadir el Haj, the first railway station south of Maan, on our direct road for Aba el Lissan. Simultaneously, we detached a small party to cross the railway just above Maan and create a diversion on that side. Especially they were to threaten the great herds of sick camels, casualties of the Palestine front, which the Turks pastured in the Shobek plains till once more fit for service.

We calculated that the news of their Fuweilah disaster would not have reached Maan till the morning, and that they could not drive in these camels (supposing our northern party missed them) and fit out a relief expedition, before nightfall; and if we were then attacking the line at Ghadir el Haj, they would probably divert the relief thither, and so let us move on Akaba unmolested.

With this hope we rode steadily through the flowing mirage till afternoon, when we descended on the line; and, having delivered a long stretch of it from guards and patrols, began on the many bridges of the captured section. The little garrison of Ghadir el Haj sallied out with the valour of ignorance against us, but the heat-haze blinded them, and we drove them off with loss.

They were on the telegraph, and would notify Maan, which beside, could not fail to hear the repeated thuds of our explosion. It was our aim to bring the enemy down upon us in the night; or rather down here, where they would find no people but many broken bridges, for we worked fast and did great damage. The drainage holes in the spandrils held from three to five pounds of gelatine each. We, firing our mines by short fuses, brought down the arch, shattered the pier, and stripped the side walls, in no more than six minutes’ work. So we ruined ten bridges and many rails, and finished our explosive.

After dusk, when our departure could not be seen, we rode five miles westward of the line, to cover. There we made fires and baked bread. Our meal however was not cooked before three horsemen cantered up to report that a long column of new troops—infantry and guns—had just appeared at Alba el Lissan from Maan. The Dhumaniyeh, disorganised with victory, had had to abandon their ground without fighting. They were at Batra waiting for us. We had lost Aba el Lissan, the blockhouse, the pass, the command of the Akaba road: without a shot being fired.

We learned afterwards that this unwelcome and unwonted vigour on the part of the Turks was accident. A relief battalion had reached Maan that very day. The news of an Arab demonstration against Fuweilah arrived simultaneously; and the battalion, which happened to be formed up ready with its transport in the station yard, to march to barracks, was hurriedly strengthened by a section of pack artillery and some mounted men, and moved straight out as a punitive column to rescue the supposedly-besieged post.

They had left Maan in midmorning and marched gently along the motor road, the men sweating in the heat of this south country after their native Caucasian snows, and drinking thirstily of every spring. From Aba el Lissan they climbed uphill towards the old blockhouse, which was deserted except for the silent vultures flying above its walls in slow uneasy rings. The battalion commander feared lest the sight be too much for his young troops, and led them back to the roadside spring of Aba el Lissan, in its serpentine narrow valley, where they camped all night in peace about the water.