XLVII

We feasted on the first day once, on the second twice, on the third twice; at Isawiya: and then, on the thirtieth of May, we saddled and rode easily for three hours, past an old sanded lava field to a valley in which seven-foot wells of the usual brackish water lay all about us. The Abu Tayi struck camp when we struck, and journeyed at our side, and camped around us: so today for the first time I was spectator from the midst of an Arab tribe, and actor in the routine of its march.

It was strangely unlike the usual desert-constancy. All day the grey-green expanse of stones and bushes quivered like a mirage with the movement of men on foot; and horsemen; men on camels; camels bearing the hunched black loads which were the goat-hair tent-cloths; camels swaying curiously, like butterflies, under the winged and fringed howdahs of the women; camels tusked like mammoths or tailed like birds with the cocked or dragging tent-poles of silvery poplar. There was no order nor control nor routine of march, other than the wide front, the self-contained parties, the simultaneous start, which the insecurity of countless generations had made instinctive. The difference was that the desert, whose daily sparseness gave value to every man, today seemed with their numbers suddenly to come alive.

The pace was easy; and we, who had been guarding our own lives for weeks, found it a relaxation beyond feeling to know ourselves so escorted as to share the light liability of danger with a host. Even our most solemn riders let themselves go a little, and the wilder ones became licentious. First amongst these, of course, were Farraj and Daud, my two imps, whose spirits not all the privations of our road had quelled for a moment. About their riding places in our line of march centred two constant swirls of activity or of accident, according as their quenchless mischief found a further expression.

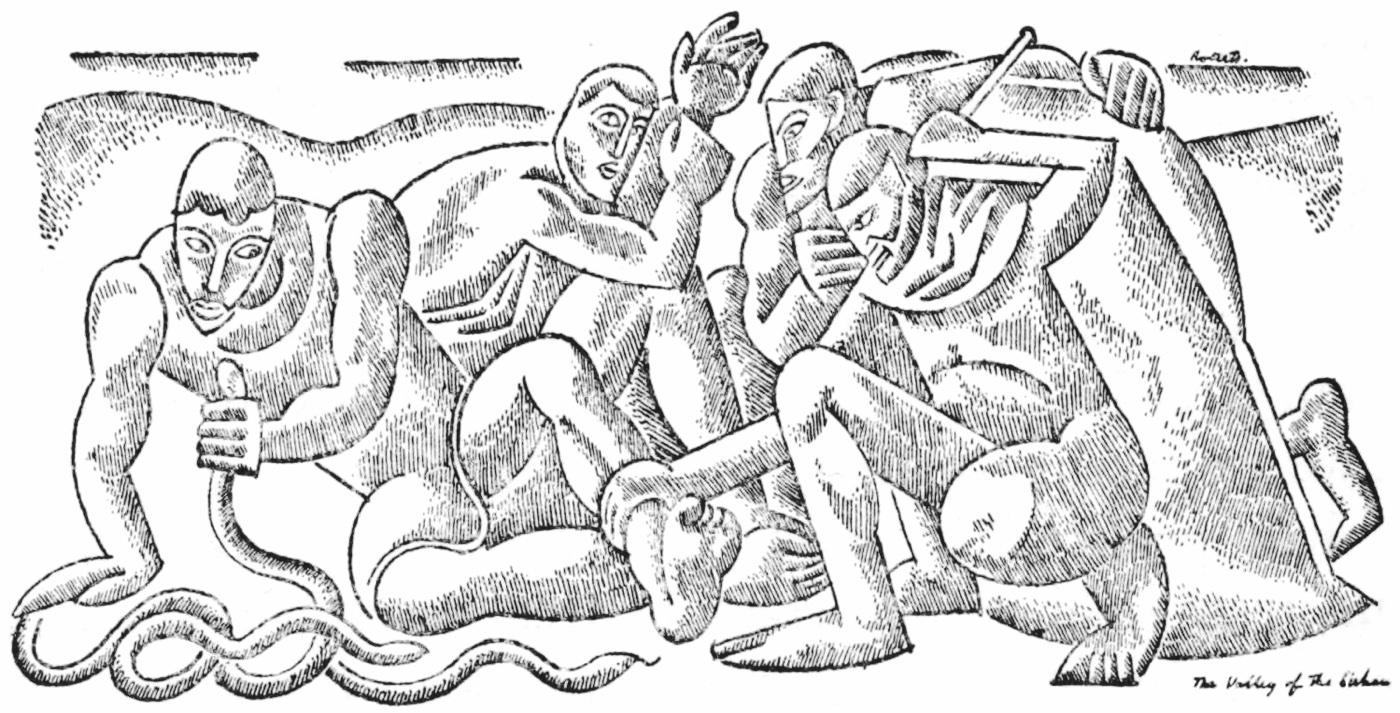

On my dry patience they grated a little, because the plague of snakes which had been with us since our first entry into Sirhan today rose to memorable height, and became a terror. In ordinary times, so the Arabs said, snakes were little worse here than elsewhere by water in the desert: but this year the valley seemed creeping with horned vipers and puff-adders, cobras and black snakes. By night movement was dangerous: and at last we found it necessary to walk with sticks, beating the bushes each side while we stepped warily through on bare feet.

We could not lightly draw water after dark, for there were snakes swimming in the pools or clustering in knots around their brinks. Twice puff-adders came twisting into the alert ring of our debating coffee-circle. Three of our men died of bites; four recovered after great fear and pain, and a swelling of the poisoned limb. Howeitat treatment was to bind up the part with snake-skin plaster, and read chapters of the Koran to the sufferer until he died. They also pulled thick Damascene ankle-boots, red, with blue tassels and horseshoe heels, over their horny feet when they went late abroad.

A strange thing was the snakes’ habit, at night, of lying beside us, probably for warmth, under or on the blanket. When we learned this our rising was with infinite care, and the first up would search round his fellows with a stick till he could pronounce them unencumbered. Our party of fifty men killed perhaps twenty snakes daily; at last they got so on our nerves that the boldest of us feared to touch ground; while those who, like myself, had a shuddering horror of all reptiles longed that our stay in Sirhan might end.

Not so Farraj and Daud. To them, this was a new and splendid game. They troubled us continually with alarms, and furious beatings upon the head of every harmless twig or root which caught their fancy. At last, in our noon-halt, I charged them strictly not to let the cry of snake again pass their lips aloud; and then, sitting by our traps upon the sand, we had peace. To live on the floor, whence it was so far to arise and walk, disposed to inaction, and there was much to think about: so that it may have been an hour afterwards before I noticed the offending pair smiling and nudging one another. My eyes idly followed their eyes to the neighbouring bush under which a brown snake lay coiled, glittering at me.

Quickly I moved myself, and cried to Ali, who jumped in with his riding-cane and settled it. I told him to give the two boys a swinging half-dozen each, to teach them not again to be literal at my expense. Nasir, slumbering behind me, heard and with joy shouted to add six from himself. Nesib copied him, and then Zeki, and then ibn Dgheithir, till half the men were clamouring for revenge. The culprits were abashed when they saw that all the hides and all the sticks in the party would hardly expiate their account: however, I saved them the weight of it, and instead we proclaimed them moral bankrupts, and set them under the women to gather wood and draw water for the tents.

So they laboured shamefully for the two days we spent at Abu Tarfeiyat; where on the first day we feasted twice and on the second day twice. Then Nesib broke down, and on plea of illness took refuge inside Nasir’s tent, and ate dry bread thankfully. Zeki had been ailing on the road, and his first effort at the Howeitat sodden meat and greasy rice had prostrated him. He also lay within the tent, breathing disgust and dysentery against us. Nasir’s stomach had had long experience of tribal ways and stood the test grandly. It was incumbent on him, for the honour of our guesting, to answer every call; and for greater honour, he constrained me always to go with him. So we two leaders represented the camp each day, with a decent proportion of the hungering Ageyl.

Of course it was monotonous; but the crystal happiness in our hosts was a return satisfaction for our eyes, and to have shattered it a crime. Oxford or Medina had tried to cure Nasir and me of superstitious prejudice; and had complicated us to the point of regaining simplicity. These people were achieving in our cause the height of nomadic ambition, a continued orgy of seethed mutton. My heaven might have been a lonely, soft armchair, a book-rest, and the complete poets, set in Caslon, printed on tough paper: but I had been for twenty-eight years well-fed, and if Arab imagination ran on food-bowls, so much the more attainable their joy. They had been provident expressly on our account. A few days before we came, a drover had guested with them; and, by Auda’s order, they had bought his fifty sheep to entertain us worthily. In fifteen meals (a week) we had consumed them all, and the hospitality guttered out.

Digestion returned, and with it our power of movement. We were very weary of Sirhan. The landscape was of a hopelessness and sadness deeper than all the open deserts we had crossed. Sand, or flint, or a desert of bare rocks was exciting sometimes, and in certain lights had the monstrous beauty of sterile desolation: but there was something sinister, something actively evil in this snake-devoted Sirhan, proliferant of salt water, barren palms, and bushes which served neither for grazing nor for firewood.

Accordingly we marched one day, and another, beyond Ghutti, whose weak well was nearly sweet. When we got near Ageila, we saw that it was held by many tents, and presently a troop came out to meet us. They were Auda abu Tayi, safely back from Nuri Shaalan, with the one-eyed Durzi ibn Dughmi, our old guest at Wejh. His presence proved Nuri’s favour, as did their strong escort of Rualla horse; who, bareheaded and yelling, welcomed us to Nuri’s empty house with a great show of spears and wild firing of rifles and revolvers at full gallop through the dust.

This modest manor had some fruitful palms, enclosed, and they had pitched beside the garden a Mesopotamian tent of white canvas. Here, also, stood Auda’s tent, a huge hall seven poles long and three wide; and Zaal’s tent was near it, and many others; and through the afternoon we received fusillades of honour, deputations, and gifts of ostrich eggs, or Damascus dainties, or camels, or scraggy horses, while the air was loud about us with the cries of Auda’s volunteers demanding service, immediate service, against the Turks.

Affairs looked well, and we set three men to make coffee for the visitors, who came in to Nasir one by one or group by group, swearing allegiance to Feisal and to the Arab Movement, in the Wejh formula; and promising to obey Nasir, and to follow after him with their contingents. Besides their formal presents, each new party deposited on our carpet their privy, accidental gift of lice; and long before sunset Nasir and I were in a fever, with relay after relay of irritation. Auda had a stiff arm, the effect of an old wound in the elbow joint, and so could not scratch all of himself; but experience had taught him a way of thrusting a cross-headed camel-stick up his left sleeve and turning it round and round inside against his ribs, which method seemed to relieve his itch more than our claws did ours.