CXIV

Before dawn, on the Australian aerodrome, stood two Bristols and a D.H.9. In one was Ross Smith, my old pilot, who had been picked out to fly the new Handley-Page, the single machine of its class in Egypt, the apple of Salmond’s eye. His lending it to fly over the enemy line on so low an errand as baggage carrying, was a measure of the goodwill toward us.

We reached Umtaiye in an hour, and saw that the army had gone: so I waved ourselves back to Um el Surab; and there they were, the defensive group of cars, and Arabs hiding from our suspect noise here, there and everywhere; the cute camels dispersed singly over the plain, filling themselves with the wonderful grazing. Young, when he saw our markings, put a landing-signal and smoke bombs on the turf which his care and Nuri Said’s had swept clear of stones.

Ross Smith anxiously paced the length and breadth of the prepared space, and studied its imperfections: but rejoined us, where the drivers were making breakfast, with a clear face. The ground was OK for the Handley-Page. Young told us of repeated bombings yesterday and the day before, which had killed some regulars and some of Pisani’s gunners, and tired the life out of everyone, so that they moved in the night to Um el Surab. The idiot Turks were still bombing Umtaiye though men went to it only in the neutral noons and nights to draw water.

Also I heard of Winterton’s last blowing up of the railway: an amusing night, in which he had met an unknown soldier and explained to him in broken Arabic how well they were getting on. The soldier had thanked God for His mercies, and disappeared in the dark; whence a moment later, machine-gun fire opened from left and right! Nevertheless, Winterton had fired all his charges, and withdrawn in good order without loss. Nasir came to us, and reported this man hurt, and that killed, this clan getting ready, those already joined, but others gone home—all the gossip of the country. The three shining aeroplanes had much restored the Arabs, who lauded the British, and their own bravery and endurance, while I told them the scarce-credible epic of Allenby’s success—Nablus taken, Afuleh taken, Beisan and Semakh and Haifa. My hearers’ minds drew after me like flames. Tallal took fire, boasting; while the Rualla shouted for instant march upon Damascus. Even my bodyguard, still bearing witness of the Zaagi’s severity in their muddy eyes and constrained faces, cheered up and began to preen a little before the crowd, with a dawn of happiness. A shiver of self-assertion and confidence ran across the camp. I determined to bring up Feisal and Nuri Shaalan for the final effort.

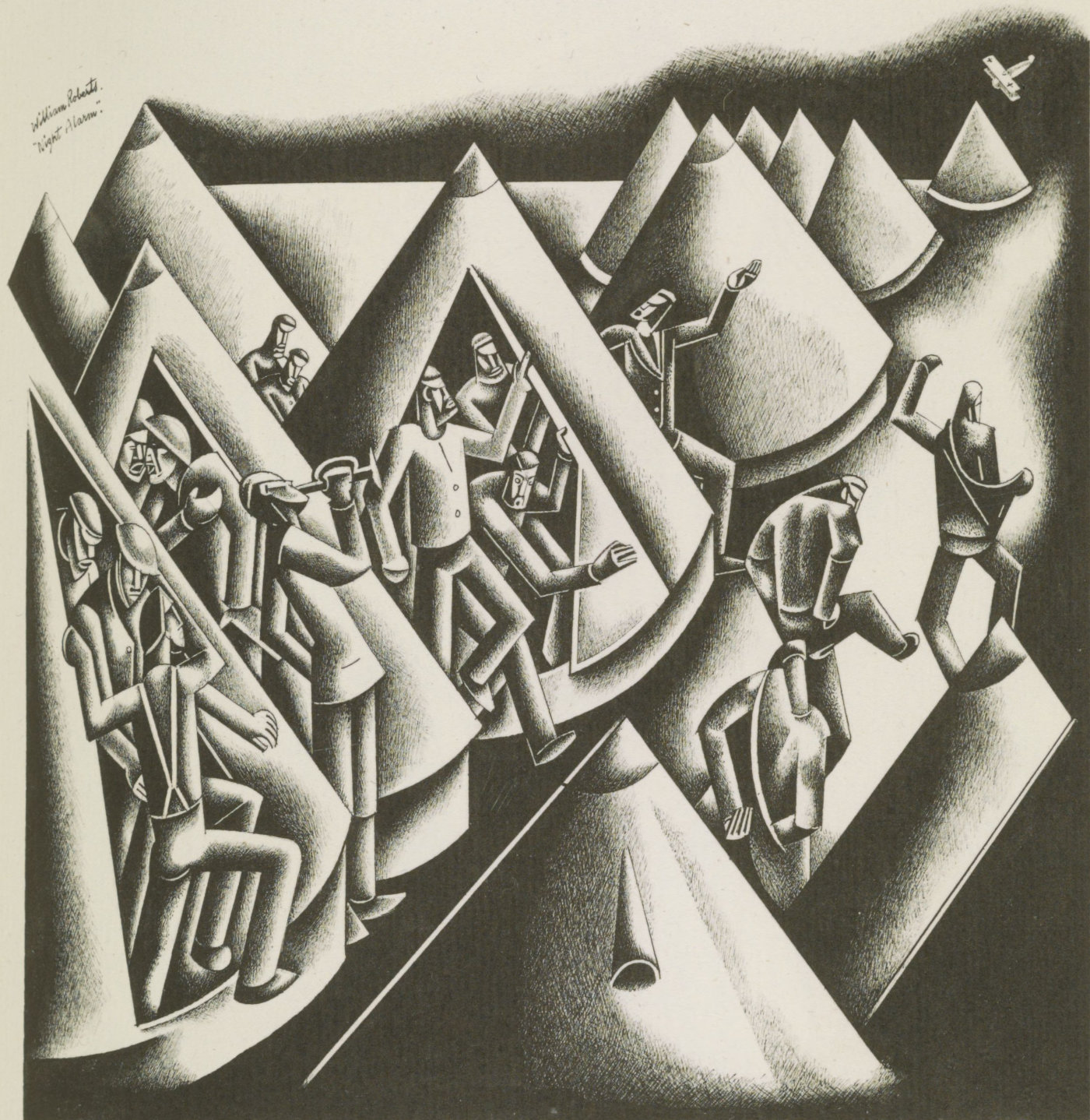

Meanwhile it was breakfast time with a smell of sausage in the air. We sat round, very ready: but the watcher on the broken tower yelled “Aeroplane up,” seeing one coming over from Deraa. Our Australians, scrambling wildly to their yet-hot machines, started them in a moment. Ross Smith, with his observer, leaped into one, and climbed like a cat up the sky. After him went Peters, while the third pilot stood beside the D.H.9 and looked hard at me.

I seemed not to understand him. Lewis guns, scarfe mountings, sights, rings which turned, vanes, knobs which rose and fell on swinging parallel bars; to shoot, one aimed with this side of the ring or with that, according to the varied speed and direction of oneself and the enemy. I had been told the theory, could repeat some of it: but it was in my head, and rules of action were only snares of action till they had run out of the empty head into the hands, by use. No: I was not going up to air-fight, no matter what caste I lost with the pilot. He was an Australian, of a race delighting in additional risks, not an Arab to whose gallery I must play.

He was too respectful to speak: only he looked reproach at me while we watched the battle in the air. There were one enemy two-seater and three scouts. Ross Smith fastened on the big one, and, after five minutes of sharp machine-gun rattle, the German dived suddenly towards the railway line. As it flashed behind the low ridge, there broke out a pennon of smoke, and from its falling place a soft, dark cloud. An “Ah!” came from the Arabs about us. Five minutes later Ross Smith was back, and jumped gaily out of his machine, swearing that the Arab front was the place.

Our sausages were still hot; we ate them, and drank tea (our last English stores, broached for the visitors), but were hardly at the grapes from Jebel Druse when again the watchman tossed up his cloak and screamed, “A plane!” This time Peters won the race, Ross Smith second, with Traill, disconsolate, in reserve: but the shy enemy turned back so soon that Peters did not catch them till near Arar: there he drove down his quarry, fighting. Later, when the wave of war rolled thither, we found the hopeless crash, and two charred German bodies.

Ross Smith wished he might stay forever on this Arab front with an enemy every half-hour; and deeply envied Peters his coming days. However, he must go back for the Handley-Page with petrol, food and spares. The third plane was for Azrak, to get the observer marooned there yesterday; and I went in it so far, to see Feisal.

Time became spacious to those who flew: we were in Azrak thirty hours after leaving it. Ghurkas and Egyptians I turned back to rejoin the army, for new demolitions in the north. Then, with Feisal and Nuri Shaalan, I packed into the green Vauxhall, and off we went for Um el Surab to see the Handley-Page alight.

We ran at speed over the smooth flint or mudflat, letting the strong car throb itself fully: but luck was hostile. A dispute was reported us, and we had to turn aside to a local Serahin camp. However, we made profit of our loss, by ordering their fighting men to Umtaiye: and we had them send word of victory across the railway, that the roads through the Ajlun hills might be closed to the broken Turkish armies, trying to escape into safety.

Then our car flashed northward again. Twenty miles short of Um el Surab we perceived a single Bedawi, running southward all in a flutter, his grey hair and grey beard flying in the wind, and his shirt (tucked up in his belly-cord) puffing out behind him. He altered course to pass near us, and, raising his bony arms, yelled, “The biggest aeroplane in the world,” before he flapped on into the south, to spread his great news among the tents.

At Um el Surab the Handley stood majestic on the grass, with Bristols and 9.A like fledglings beneath its spread of wings. Round it admired the Arabs, saying, “Indeed and at last they have sent us the aeroplane, of which these things were foals.” Before night rumour of Feisal’s resource went over Jebel Druse and the hollow of Hauran, telling people that the balance was weighted on our side.

Borton himself had come over in the machine, to concert help. We talked with him while our men drew from her bomb-racks and fuselage a ton of petrol; oil and spare parts for Bristol fighters; tea and sugar and rations for our men; letters, Reuter telegrams and medicines for us. Then the great machine rose into the early dusk, for Ramleh, with an agreed programme of night-bombing against Deraa and Mafrak, to complete that ruin of the railway traffic which our guncotton had begun.

We, for our share, would keep up the guncotton pressure. Allenby had assigned us the Turkish Fourth Army, to harass and contain till Chaytor forced them out of Amman; and afterwards to cut up, on their retreat. This retreat was only an affair of days, and it was as certain as things could be in war that we should raise the plains between us and Damascus next week. So Feisal decided to add to our column Nuri Shaalan’s Rualla camel men from Azrak. It would increase us to about four thousand strong, more than three-fourths irregular; but reliably so, for Nuri, the hard, silent, cynical old man, held the tribe between his fingers like a tool.

He was that rarity in the desert, a man without sense of argument. He would or would not, and there was no more to it. When others finished talking, he would announce his will in a few flat phrases, and wait calmly for obedience; which came, for he was feared. He was old and wise, which meant tired and disappointed: so old that it was my abiding wonder he should link himself to our enthusiasm.

I rested next day in Nasir’s tent, among his peasant visitors; sorting out the too-abundant news furnished by their quick wit and goodwill. During my rest-day, Nuri Said, with Pisani and two guns, Stirling, Winterton, Young, their armoured cars, and a considerable force, went openly to the railway, cleared it by approved military means, destroyed a kilometre of rail, and burnt the tentative wooden structure with which the Turks were mending the bridge blown up by Joyce and myself before our first attack on Deraa. Nuri Shaalan, in black broadcloth cloak, personally led his Rualla horsemen, galloping with the best of them. Under his eye the tribe showed a valour which drew praise even from Nuri Said.