II

The Ascent of Mont Pelvoux

“Thus fortune on our first endeavour smiles.”

Virgil

The district of which Mont Pelvoux and the neighbouring summits are the culminating points,9 is, both historically and topographically, one of the most interesting in the Alps. As the nursery and the home of the Vaudois, it has claims to permanent attention. The names of Waldo and of Neff will be remembered when men more famous in their time will be forgotten; and the memory of the heroic courage and the simple piety of their disciples will endure as long as history lasts.

This district contains the highest summits in France, and some of its finest scenery. It has not perhaps the beauties of Switzerland, but has charms of its own. Its cliffs, torrents, and gorges are unsurpassed; its deep and savage valleys present pictures of grandeur, and even sublimity, and it is second to none in the boldness of its mountain forms.

The district includes a mass of valleys which vie with each other in singularity of character and dissimilarity of climate. Some the rays of the sun can never reach, they are so deep and narrow.10 In others the very antipodes may be found; with temperature more like that of the plains of Italy than of Alpine France. This great range of climate has a marked effect on the flora of these valleys. Sterility reigns in some; stones take the place of trees; debris and mud replace plants and flowers: while in others, in a few miles, one passes vines, apple, pear, and cherry trees, the birch, alder, walnut, ash, larch, and pine, alternating with fields of rye, barley, oats, beans, and potatoes.

The valleys are for the most part short and erratic. They are not, apparently, arranged on any definite plan. They are not disposed, as is frequently the case elsewhere, either at right angles to, or parallel with, the highest summits; but they wander hither and thither, take one direction for a few miles, then double back, and then perhaps resume their original course. Thus, long perspectives are rarely to be seen, and it is difficult to form a general idea of the disposition of the peaks.

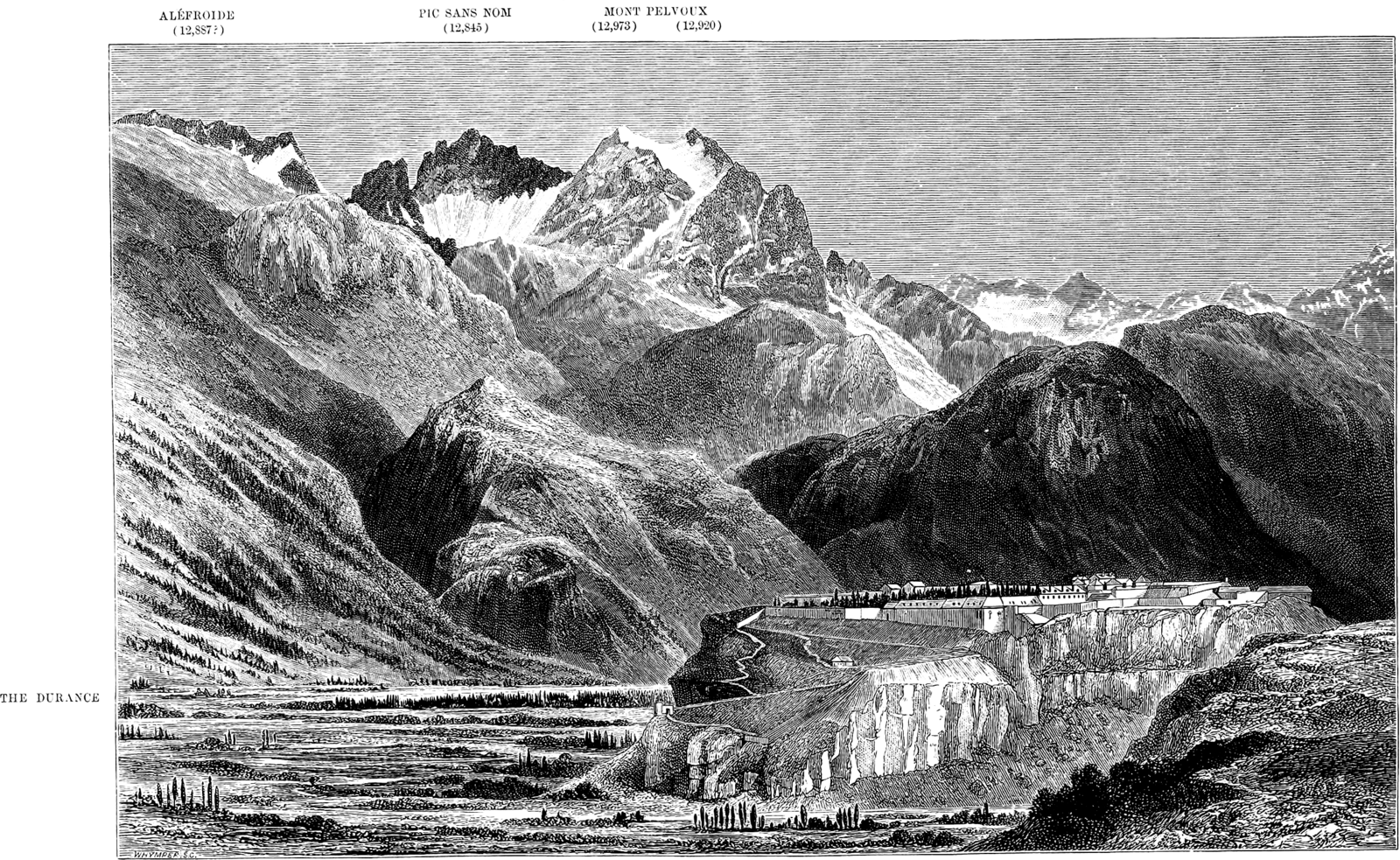

The highest summits are arranged almost in a horseshoe form. The loftiest of all, which occupies a central position, is the Pointe des Écrins; the second in height, the Meije,11 is on the north; and the Mont Pelvoux, which gives its name to the entire block, stands almost detached by itself on the outside.

The district is still very imperfectly known; there are probably many valleys, and there are certainly many summits which have never been trodden by the feet of tourists or travellers; but in it was even less known. Until quite recently there was, practically, no map of it; General Bourcet’s, which was the best that was published, was completely wrong in its delineation of the mountains, and was frequently incorrect in regard to paths or roads.

The mountainous regions of Dauphiné, moreover, are not supplied, like Switzerland, the Tyrol, or even the Italian valleys, with accommodation for travellers. The inns, when they exist, are often filthy beyond description. Rest is seldom obtained in their beds, or decent food found in their kitchens, and guides there are none. The tourist is thrown very much on his own resources, and it is not therefore surprising that these districts are less visited and less known than the rest of the Alps.12

Most of the statements current in respecting these mountains had been derived from two authors13—M. Elie de Beaumont and the late Principal J. D. Forbes. Their works, however, contained numerous errors in regard to the identification of the peaks, and, amongst others, they referred the supremacy to the Mont Pelvoux, the highest point of which they termed the Pointe des Arcines, or des Écrins. Principal Forbes erroneously identified the high peak seen from the Valley of St. Christophe, with that seen from the Valley of the Durance, and spoke of both as the Mont Pelvoux, and M. de Beaumont committed similar mistakes. In point of fact, at the time when M. de Beaumont and Forbes wrote their respective memoirs, the proper relation of the Mont Pelvoux to the neighbouring summits had been determined by the engineers employed on the survey for the map of France, but their observations were not then accessible to the public, although they had evidently been seen by M. de Beaumont. This party of surveyors, led by Captain Durand, made the ascent of Mont Pelvoux from the side of the Val d’Ailefroide—that is, from the direction of Val Louise—in . According to the natives of the Val Louise, they got to the top of the second peak in height, and remained upon it, lodged in a tent for several days, at a height of 12,904 feet. They took numerous porters to carry wood for fires, and erected a large cairn on the summit, which has caused the name of Pic de la Pyramide to be given to their summit.

In , M. Puiseux made the ascent from the same direction, but his Val Louisan guide stopped short of the summit, and allowed this courageous astronomer to proceed by himself.14

In the middle of , Messrs. Bonney, Hawkshaw, and Mathews, with Michel Croz of Chamounix, tried to ascend the Pelvoux, likewise from the same direction. These gentlemen spent several days and nights upon the mountain; and, encountering bad weather, only attained a height of 10,430 feet.

M. Jean Reynaud, of whom mention has been made in the preceding chapter, accompanied the party of Mr. Mathews, and he was of opinion that the attempt had been made too late in the season. He said that the weather was usually good enough for high mountain ascents only during the last few days of July, and the first ones of August,15 and suggested that we should attempt to ascend the mountain in the following year at that time. The proposition was a tempting one, and Reynaud’s cordial and modest manner made it irresistible, although there seemed small chance that we should succeed where a party such as that of Mr. Mathews had been beaten.

At the beginning of , I despatched to Reynaud from Havre, blankets (which were taxed as “prohibited fabrics”), rope, and other things desirable for the excursion, and set out on the tour of France; but, four weeks later, at Nîmes, found myself collapsed by the heat, then 94° F in the shade, so I took a night train at once to Grenoble.

I lost my way in the streets of this picturesque but noisome town,16 and having only a half-hour left in which to get a dinner and take a place in the diligence, was not well pleased to hear that an Englishman wished to see me. It turned out to be my friend Macdonald, who confided to me that he was going to try to ascend a mountain called Mont Pelvoux in the course of ten days; but, on hearing of my intentions, he agreed to put in an appearance at La Bessée on the . In a few moments more I was perched in the banquette en route for Bourg d’Oysans, in a miserable vehicle which took nearly eight hours to accomplish less than thirty miles.

At five on a lovely morning I shouldered my knapsack and started for Briançon. Gauzy mists clung to the mountains, but melted away when touched by the sun, and disappeared by jerks (in the manner of views when focused in a magic lantern), revealing the wonderfully bent and folded strata in the limestone cliffs behind the town. Then I entered the Combe de Malval, and heard the Romanche eating its way through that wonderful gorge, and passed on to Le Dauphin, where the first glacier came into view, tailing over the mountain side on the right. From this place until the summit of the Col de Lautaret was passed, every gap in the mountains showed a glittering glacier or a soaring peak. The finest view was at La Grave, where the Meije rises by a series of tremendous precipices 8,000 feet above the road.17 The finest distant view of the pass is seen after crossing the Col, near Monêtier. A mountain, commonly supposed to be Monte Viso, appears at the end of the vista, shooting into the sky;18 in the middle distance, but still ten miles off, is Briançon with its interminable forts, and in the foreground, leading down to the Guisane, and rising high up the neighbouring slopes, are fertile fields, studded with villages and church spires. The next day I walked over from Briançon to La Bessée, to my worthy friend Jean Reynaud, the surveyor of roads of his district.

All the peaks of Mont Pelvoux are well seen from La Bessée, the highest point, as well as that upon which the engineers erected their cairn. Neither Reynaud nor anyone else knew this. The natives knew only that the engineers had ascended one peak, and had seen from that a still higher point, which they called the Pointe des Arcines or des Écrins. They could not say whether this latter could be seen from La Bessée, nor could they tell the peak upon which the cairn had been erected. They knew nothing of the ascent of Monsieur Puiseux, and they confidently asserted that the highest point of Mont Pelvoux had not been attained by anyone. It was this point we wished to reach, and we were under the impression that the highest point was concealed by the peaks we saw, and would be gained by passing over them.

Nothing prevented our starting at once but the absence of Macdonald and the want of a baton. Reynaud suggested a visit to the postmaster, who possessed a weapon of local celebrity. Down we went to the bureau; but it was closed; we halloed through the slits, but no answer. At last the postmaster was discovered endeavouring (with very fair success) to make himself intoxicated. He was just able to ejaculate, “France! ’tis the first nation in the world!” which is a phrase used by a Frenchman at times that a Briton begins to shout, “We won’t go home till morning”—national glory being uppermost in the thoughts of one, and home in those of the other. The baton was produced; it was a branch of a young oak, about five feet long, gnarled and twisted in several directions. “Sir,” said the postmaster, as he presented it, “France! ’tis the first—the first nation in the world, by its”—he stuck. “Batons?” I suggested. “Yes, yes, sir; by its batons, by its—its,” and here he could not get on at all. As I looked at this young limb, I thought of my own; but Reynaud, who knew everything about everybody in the village, said there was not a better one, and we went off with it, leaving the official staggering in the road, muttering, “France! ’tis the first nation in the world!”

The came, and as Macdonald did not appear, we started for the Val Louise; our party consisting of Reynaud, myself, and a porter, Jean Casimir Giraud, nicknamed “little nails,” the shoemaker of the place. An hour and a half’s smart walking took us to La Ville de Val Louise, our hearts gladdened by the glorious peaks of Pelvoux shining out without a cloud around them. I renewed acquaintance with the mayor of “La Ville.” His aspect was original, and his manners were gracious, but the odour which proceeded from him was dreadful. The same may be said of many of the inhabitants of these valleys.19

At “La Ville” the Val Louise splits into two branches—the Val d’Entraigues on the left and the Vallon d’Alefred (or Ailefroide) on the right. Our route was up the latter, and we moved steadily forwards to the village of La Pisse, where a certain Pierre Sémiond lived, who was reputed to know more about Mont Pelvoux than any other man. He looked an honest fellow, but unfortunately he was ill and could not come. He recommended his brother, an aged creature, whose furrowed and wrinkled face hardly seemed to announce the man we wanted. Having no choice, we engaged him and again set forth.

Walnut and a great variety of other trees gave shadow to our path and fresh vigour to our limbs; while below, in a sublime gorge, thundered the torrent, whose waters took their rise from the snows we hoped to tread on the morrow.

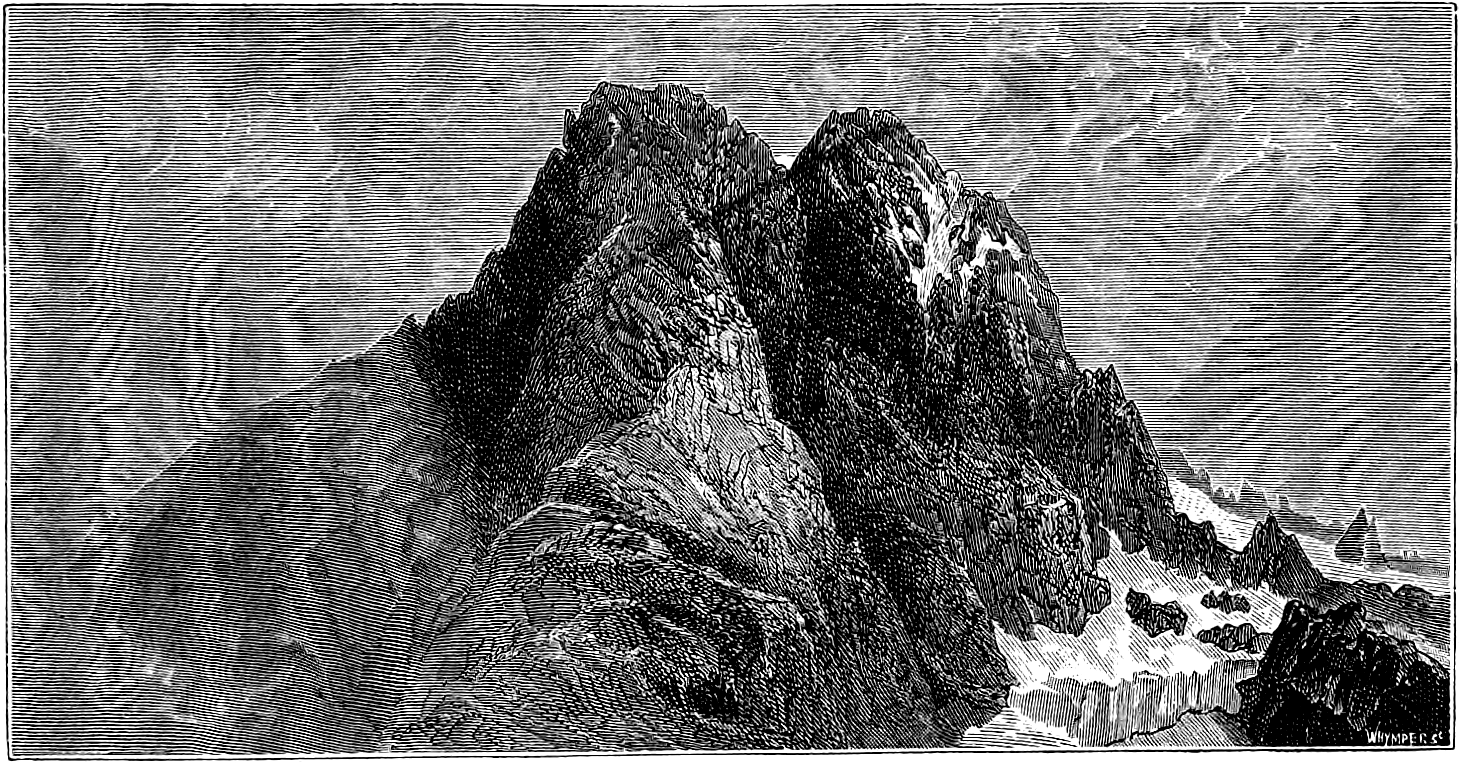

The mountain could not be seen at La Ville, owing to a high intervening ridge. We were now moving along the foot of this to get to the chalets of Alefred (or, as they are sometimes called, Aléfroide), where the mountain actually commences. From this direction the subordinate, but more proximate peaks appear considerably higher than the loftier ones behind, and sometimes completely conceal them. But the whole height of the peak which in these valleys goes under the name of the “Grand Pelvoux” is seen at one glance from summit to base, six or seven thousand feet of nearly perpendicular cliffs.

The chalets of Alefred are a cluster of wooden huts at the foot of the Grand Pelvoux, and are close to the junction of the streams which descend from the Glacier de Sapenière (or du Selé) on the left, and the Glaciers Blanc and Noir on the right. We rested a minute to purchase some butter and milk, and Sémiond picked up a disreputable-looking lad to assist in transporting our stores.

Our route now turned sharply to the left, and all were glad that the day was drawing to a close, so that we had shade from the mountains. A more cheerless and desolate valley it is scarcely possible to imagine. It contains miles of boulders, debris, stones, sand, and mud; few trees, and they placed so high as to be almost out of sight. Not a soul inhabits it. The mountains are too steep for the chamois, too inhospitable for the marmot, and too repulsive for the eagle. We did not see a single living thing in this sterile and savage valley during four days, except some few poor goats which had been driven there against their will.

It was a scene in keeping with the diabolical deed perpetrated here about four hundred years ago—the murder of the Vaudois of Val Louise, in the cavern which was now in sight, though high above us. Their story is very sad. Peaceful and industrious, for more than three centuries they had inhabited these retired valleys in tranquil obscurity. The Archbishops of Embrun endeavoured, though with little success, to get them within the pale of their church; their efforts were aided by others, who commenced by imprisonments and torture,20 and at last adopted the method of burning them by hundreds at the stake.21

In the year , Albert Cattanée, Archdeacon of Cremona and legate of Pope Innocent VIII, would have anticipated the barbarities which at a later date roused the indignation of Milton and the fears of Cromwell;22 but, driven everywhere back by the Waldenses of Piedmont, he left their valleys and crossed the Mont Genèvre to attack the weaker and more thinly populated valleys of the Vaudois in Dauphiné. At the head of an army which is said to have been composed of vagabonds, robbers, and assassins (who had been tempted to his banner by promises of absolution beforehand, of being set free from the obligation of vows which they might have made, and by the confirmation of property to them which they might have wrongfully acquired), as well as regular troops, Cattanée poured down the Valley of the Durance. The inhabitants of the Val Louise fled before a host that was ten times their number, and took up their abode in this cavern, where they had collected provisions sufficient for two years. But intolerance is ever painstaking; their retreat was discovered. Cattanée had a captain who combined the resources of a Herod with the cruelty of a Pelissier, and, lowering his men by ropes, fired piles of brushwood at the entrance to the cavern, suffocated the majority, and slew the remainder. The Vaudois were relentlessly exterminated, without distinction of age or sex. More than three thousand persons, it is said, perished in this massacre; the growth of three hundred and fifty years was destroyed at one blow, and the valley was completely depopulated. Louis XII caused it to be re-peopled, and after another three centuries and a half, behold the result—a race of monkeys.23

We rested a little at a small spring, and then hastened onwards till we nearly arrived at the foot of the Sapenière Glacier, when Sémiond said we must turn to the right, up the slopes. This we did, and clambered for half-an-hour through scattered trees and fallen boulders. Then evening began to close in rapidly, and it was time to look for a resting-place. There was no difficulty in getting one, for all around there was a chaotic assemblage of rocks. We selected the under side of a boulder which was more than fifty feet long by twenty high, cleared out the rubbish, and then collected wood for a fire.

That campfire is a pleasant reminiscence. The wine-cask had got through all its troubles; it was tapped, and the Frenchmen seemed to derive some consolation from its execrable contents. Reynaud chanted scraps of French songs, and each contributed his share of joke, story, or verse. The weather was perfect, and our prospects for the morrow were good. My companions’ joy culminated when some red fire was thrown into the flames. It hissed and bubbled for a moment or two, and then broke out into a grand flare. The effect of the momentary light was magnificent; the mountains all around were illuminated for a second, and then relapsed into their solemn gloom. One by one our party dropped off to sleep, and at last I got into my blanket bag. It was hardly necessary, for, although we were at a height of about 7,000 feet, the minimum temperature was above 40° Fahrenheit.

We roused at three, and made a start at half-past four. Giraud had been engaged as far as this rock only, but as he wished to go on, we allowed him to accompany us. We mounted the slopes and quickly got above the trees, then had a couple of hours’ clambering over bits of precipitous rock and banks of debris, and, at a quarter to seven, got to a narrow glacier—Clos de l’Homme—which streamed out of the plateau on the summit, and nearly reached the Glacier de Sapenière. We worked as much as possible to the right, in hopes that we should not have to cross it, but were continually driven back, and found that it could not be avoided. Old Sémiond had a strong objection to travel on the ice, and made explorations on his own account to endeavour to escape it; but Reynaud and I preferred to cross, and Giraud stuck to us. This glacier was narrow—in fact, one could throw a stone across it—and it was easily mounted on the side; but in the centre it swelled into a steep dome, up which we were obliged to cut. Giraud stepped forward and said he should like to try his hand, and having got hold of the axe, would not give it up; and here, as well as afterwards when it was necessary to cross the gullies filled with hard snow, which abound on the higher part of the mountain, he did all the work, and did it efficiently.

Old Sémiond of course came after us when we got across. We then zigzagged up some snow-slopes, and shortly afterwards commenced to ascend the interminable array of buttresses which are the great peculiarity of Mont Pelvoux. The rocks were very steep in many places, yet on the whole afforded good hold, and no climbing should be called difficult which does that. Gullies abounded among them, sometimes of great length and depth. They were frequently rotten, and would have been difficult for a single man to pass. The uppermost men were continually abused for dislodging rocks and for harpooning those below with their batons. However, without these incidents the climbing would have been dull—they helped to break the monotony.

We went up chimneys and gullies by the hour together, and always seemed to be coming to something, although we never got to it. The outline sketch will help to explain the situation. We stood at the foot of a great buttress—perhaps about 200 feet high—and looked up. It did not go to a point as in the diagram, because we could not see the top; although we felt convinced that behind the fringe of pinnacles we did see there was a top, and that it was the edge of the plateau we so much desired to attain. Up we mounted, and reached the pinnacles; but, lo! another set was seen—and another—and yet more—till at last we reached the top, and found it was only a buttress, and that we had to descend 40 or 50 feet before we could commence to mount again. When this operation had been performed a few dozen times it began to be wearisome, especially as we were somewhat in the dark as to our whereabouts. Sémiond, however, encouraged us, and said he knew we were on the right route—so away we went once more.

It was now nearly midday, and we seemed no nearer the summit of the Pelvoux than when we started. At last we all joined together and held a council. “Sémiond, old friend, do you know where we are now?” “Oh yes, perfectly, to a yard and a half.” “Well, then, how much are we below this plateau?” He affirmed we were not half-an-hour from the edge of the snow. “Very good; let us proceed.” Half-an-hour passed, and then another, but we were still in the same state—pinnacles, buttresses, and gullies were in profusion, but the plateau was not in sight. Then we called him again—for he had been staring about latterly, as if in doubt—and repeated the question. “How far below are we now?” Well, he thought it might be half-an-hour more. “But you said that just now! Are you sure we are going right?” “Yes, he believed we were.” Believed! that would not do. “Are you sure we are going right for the Pic des Arcines?” “Pic des Arcines!” he ejaculated in astonishment, as if he had heard the words for the first time. “Pic des Arcines; no! but for the pyramid, the celebrated pyramid he had helped the great Capitaine Durand,” etc.

Here was a fix;—we had been talking about it to him for a whole day, and now he confessed he knew nothing about it. I turned to Reynaud, who seemed thunderstruck. “What did he suggest?” He shrugged his shoulders. “Well,” we said, after expressing our minds pretty freely to Sémiond, “the sooner we turn back the better, for we have no wish to see your pyramid.”

We halted for an hour, and then commenced the descent. It took us nearly seven hours to come down to our rock; but I paid no heed to the distance, and do not remember anything about it. When we got down we made a discovery which affected us as much as the footprint in the sand did Robinson Crusoe: a blue silk veil lay by our fireside. There was but one explanation—Macdonald had arrived; but where was he? The baggage was soon packed, and we tramped in the dusk, through the stony desert, to Alefred, where we arrived about half-past nine. “Where is the Englishman?” was the first question. He was gone to sleep at La Ville.

We passed that night in a hayloft, and in the morning, after settling with Sémiond, we posted down to catch Macdonald. We had already determined on the plan of operation, which was to get him to join us, return, and be independent of all guides, simply taking the best man we could get as a porter. I set my heart on Giraud—a good fellow, with no pretence, although well up to the work. We were disappointed; he was obliged to go to Briançon.

The walk soon became exciting. The natives inquired the result of our expedition, and common civility obliged us to stop. But I was afraid of losing my man, for it was said he would wait only till ten o’clock, and that time was near at hand. At last I dashed over the bridge—time from Alefred an hour and a quarter. A cantonnier stopped me, saying that the Englishman had just started for La Bessée. I rushed after him, turned angle after angle of the road, but could not see him; at last, as I came round a corner, he was also just turning another, going very fast. I shouted, and luckily he heard me. We returned, reprovisioned ourselves at La Ville, and the same evening saw us passing our first rock, en route for another. I have said we determined to take no guide; but, on passing La Pisse, old Sémiond turned out and offered his services. He went well, in spite of his years and disregard of truth. “Why not take him?” said my friend. So we offered him a fifth of his previous pay, and in a few seconds he closed with the offer. This time he came in an inferior position—we were to lead, he to follow. Our second porter was a youth of twenty-seven years, who was not all that could be desired. He drank Reynaud’s wine, smoked our cigars, and quietly secreted the provisions when we were nearly starving. Discovery of his proceedings did not at all disconcert him, and he finished up by getting several items added to our bill at La Ville, which, not a little to his disgust, we disallowed.

This night we fixed our camp high above the tree-line, and indulged ourselves in the healthy employment of carrying our fuel up to it. The present rock was not so comfortable as the first, and, before we could settle down, we were obliged to turn out a large mass which was in the way. It was very obstinate, but moved at length; slowly and gently at first, then faster and faster, at last taking great jumps in the air, striking a stream of fire at every touch, which shone out brightly as it entered the gloomy valley below, and long after it was out of sight we heard it bounding downwards, and then settle with a subdued crash on the glacier beneath. As we turned back from this curious sight, Reynaud asked if we had ever seen a torrent on fire, and said that in the spring, the Durance, swollen by the melting of the snow, sometimes brings down so many rocks, that, where it passes through a narrow gorge at La Bessée, no water whatever is seen, but only boulders rolling over and over, grinding each other into powder, and striking so many sparks that the stream looks as if it were on fire.

We had another merry evening with nothing to mar it; the weather was perfect, and we lay backward in luxurious repose, looking at the sky spangled with its ten thousand brilliant lights.

… “The ranges stood

Transfigured in the silver flood,

Their snows were flashing cold and keen,

Dead white, save where some sharp ravine

Took shadow, or the sombre green

Of hemlocks turned to pitchy black,

Against the whiteness at their back.”24

Macdonald related his experiences over the café noir. He had travelled day and night for several days in order to join us, but had failed to find our first bivouac, and had camped a few hundred yards from us under another rock, higher up the mountain. The next morning he discerned us going along a ridge at a great height above him, and as it was useless to endeavour to overtake us, he lay down and watched with a heavy heart until we had turned the corner of a buttress, and vanished out of sight.

Nothing but the heavy breathing of our already sound asleep comrades broke the solemn stillness of the night. It was a silence to be felt. Nothing? Hark! what is that dull booming sound above us? Is that nothing? There it is again, plainer—on it comes, nearer, clearer; ’tis a crag escaped from the heights above! What a fearful crash! We jump to our feet. Down it comes with awful fury; what power can withstand its violence? Dancing, leaping, flying; dashing against others; roaring as it descends. Ah, it has passed! No; there it is again, and we hold our breath, as, with resistless force and explosions like artillery, it darts past, with an avalanche of shattered fragments trailing in its rear! ’Tis gone, and we breathe more freely as we hear the finale on the glacier below.25

We retired at last, but I was too excited to sleep. At a quarter-past four every man once more shouldered his pack and started. This time we agreed to keep more to the right, to see if it were not possible to get to the plateau without losing any time by crossing the glacier. To describe our route would be to repeat what has been said before. We mounted steadily for an hour and a half, sometimes walking, though more frequently climbing, and then found, after all, that it was necessary to cross the glacier. The part on which we struck came down a very steep slope, and was much crevassed. The word crevassed hardly expresses its appearance—it was a mass of formidable seracs. We found, however, more difficulty in getting on than across it; and, thanks to the rope, it was passed in safety. Then the interminable buttresses began again. Hour after hour we proceeded upwards, frequently at fault, and obliged to descend. The ridge behind us had sunk long ago, and we looked over it, and all others, till our eyes rested on the majestic Viso. Hour after hour passed, and monotony was the order of the day. When twelve o’clock came we contemplated the scene with satisfaction. All the summits in sight, with the single exception of the Viso, had given in, and we looked over an immense expanse of peaks and snowfields. Still the pinnacles rose above us, and opinions were freely uttered that we should see no summit of Pelvoux that day. Old Sémiond had become a perfect bore. Whenever one rested for a moment to look about, he would say, with a complacent chuckle, “Don’t be afraid, follow me.” We came at last to a very bad piece, rotten and steep, and giving no hold. Here Reynaud and Macdonald confessed to being tired, and talked of going to sleep. A way was discovered out of the difficulty; then someone called out, “Look at the Viso,” and we saw that we almost looked over it. We worked away with redoubled energy, and at length caught sight of the head of the glacier as it streamed out of the plateau. This gave us fresh hopes; we were not deceived; and with a simultaneous shout we greeted the appearance of our long-wished-for snows. A large crevasse separated us from them, but a bridge was found, we tied ourselves in line, and moved safely over it. Directly we got across there rose before us a fine snow-capped summit. Old Sémiond cried, “The pyramid! I see the pyramid!” “Where, Sémiond, where?” “There; on the top of that peak.”

There, sure enough, was the cairn he had helped to erect more than thirty years before. But where was the Pic des Arcines which we were to see? It was invisible, and somewhat sadly we moved towards the pyramid, sighing that there was nothing to conquer. Hardly had we gone two hundred paces, before there rose a superb white cone on the left, which had been hidden before by a slope of snow. We shouted—“The Pic des Arcines!” and inquired of Sémiond if he knew whether that peak had been ascended. As for him, he knew nothing, except that the summit before us was called the pyramid, from the cairn he had, etc. etc., and that it had not been ascended since. “All right then—face about,” and we immediately turned at right angles for the cone, the porter making faint struggles for his beloved pyramid. Our progress was stopped, in the sixth of a mile, by the edge of the ridge connecting the two peaks, and we perceived that it curled over in a lovely volute. We involuntarily retreated. Sémiond, who was last in the line, took the opportunity to untie himself, and refused to come on; said we were running dangerous risks, and talked vaguely of crevasses. We tied him up again, and proceeded. The snow was very soft; we were always knee-deep, and sometimes floundered in up to the waist; but a simultaneous jerk before and behind always released one. By this time we had arrived at the foot of the final peak. Its left-hand ridge seemed easier than that upon which we stood, so we curved round to get to it. Some rocks peeped out 150 feet below the summit, and up these we crawled, leaving our porter behind, as he said he was afraid. I could not resist the temptation, as we went off, to turn round and beckon him onwards, saying, “Don’t be afraid—follow me,” but he did not answer to the appeal, and never went to the top. The rocks led to a short ridge of ice—our plateau on one side, and a nearly vertical precipice on the other. Macdonald cut up it, and at a quarter to two we stood shaking hands on the loftiest summit of the conquered Pelvoux.

The day still continued all that could be desired, and, far and near, countless peaks burst into sight, without a cloud to hide them. The mighty Mont Blanc, full seventy miles away, first caught our eyes, and then, still farther off, the Monte Rosa group; while, rolling away to the east, one unknown range after another succeeded in unveiled splendour; fainter and fainter in tone, though still perfectly defined, till at last the eye was unable to distinguish sky from mountain, and they died away in the far-off horizon. Monte Viso rose up grandly, but it was less than forty miles away, and we looked over it to a hazy mass we knew must be the plains of Piedmont. Southwards a blue mist seemed to indicate the existence of the distant Mediterranean, and to the west we looked over to the mountains of Auvergne. Such was the panorama; a view extending in nearly every direction for more than one hundred miles. It was with some difficulty we wrenched our eyes from the more distant objects to contemplate the nearer ones. Mont Dauphin was very conspicuous, but La Bessée was not readily perceived. Elsewhere not a human habitation could be seen; all was rock, snow, or ice; and, large as we knew were the snowfields of Dauphiné, we were surprised to find that they very far surpassed our most ardent imagination. Nearly in a line between us and the Monte Viso, immediately to the south of Château Queyras, was a splendid group of mountains of great height. More to the south an unknown peak seemed still higher; while close to us we were astonished to discover that there was a mountain which appeared even loftier than that on which we stood. At least this was my opinion. Macdonald thought that it was not so high, and Reynaud that it was much about the same elevation as our own peak.

This mountain was distant a couple of miles or so, and was separated from us by a tremendous abyss, the bottom of which we could not see. On the other side rose this mighty wall-sided peak, too steep for snow, black as night, with sharp ridges and pointed summit. We were in complete ignorance of its whereabouts, for none of us had been on the other side. We imagined that La Bérarde was in the abyss at our feet, but it was in reality beyond the other mountain.26

We left the summit at last, and descended to the rocks, where I boiled some water, obtained by melting snow. After we had fed, and smoked our cigars (lighted without difficulty from a common match), we found it was ten minutes past three, and high time to be off. We dashed, waded, and tumbled for twenty-five minutes through the snow, and then began the long descent of the cliffs. It was then nearly four o’clock, and, as it would be dark at eight, it was evident that there was no time to be lost, and we pushed on to the utmost. Nothing remarkable occurred going down. We kept rather closer to the glacier, and crossed at the same point as in the morning. Getting off it was like getting on it—rather awkward. Old Sémiond had got over—so had Reynaud; Macdonald came next, but, as he made a long stretch to get on to a higher mass, he slipped, and would have been in the bowels of a crevasse in a moment had he not been tied.

It was nearly dark by the time we had crossed, but I still hoped that we should be able to pass the night at our rock. Macdonald was not so sanguine, and he was right; for at last we found ourselves quite at fault, and wandered helplessly up and down for an hour, while Reynaud and the porter indulged in a little mutual abuse. The dreary fact that, as we could not get down, we must stay where we were, was now quite apparent.

We were at least 10,500 feet high, and if it commenced to rain or snow, as the gathering clouds and rising wind seemed to threaten, we might be in a sore plight. We were hungry, having eaten little since 3 a.m., and a torrent we heard close at hand, but could not discover, aggravated our thirst. Sémiond endeavoured to get some water from it; and, although he succeeded in doing so, he was wholly unable to return, and we had to solace him by shouting at intervals through the night.

It would be difficult to select a more detestable locality for a night out of doors. There was not shelter of any kind, and it was too steep to promenade. Loose rubbly stones covered the ground, and had to be removed before we could sit with any comfort. This was an advantage, although we hardly thought so at the time, as it gave us some employment; and, after an hour’s active exercise of that interesting kind, I obtained a small strip about nine feet long, on which it was possible to walk. Reynaud was furious at first, and soundly abused the porter, whose opinion as to the route had been followed rather than that of our friend, and at last settled down to a deep dramatic despair, and wrung his hands with frantic gesture, as he exclaimed, “Oh, malheur, malheur! Oh misérables!”

Thunder commenced to growl, and lightning to play among the peaks above, and the wind, which had brought the temperature down to nearly freezing-point, began to chill us to the bones. We examined our resources. They were six and a half cigars, two boxes of vesuvians, one-third of a pint of brandy-and-water, and half-a-pint of spirits of wine. The spirit-lamp was lighted, and the remaining spirits of wine, the brandy and some snow were heated by it. It made a strong liquor, but we only wished for more of it. When that was over, Macdonald endeavoured to dry his socks by the lamp, and then the three lay down under my plaid to pretend to sleep. Reynaud’s woes were aggravated by toothache; Macdonald somehow managed to close his eyes.

The longest night must end, and ours did at last. We got down to our rock in an hour and a quarter, and found the lad not a little surprised at our absence. We feasted at the cave, and performed some very necessary ablutions. The persons of the natives are infested by certain agile creatures, rapid of motion, numerous and voracious. It is dangerous to approach too near, and one has to study the wind, so as to get on their weather side. In spite of all such precautions my unfortunate companion and myself were being rapidly devoured alive. We only expected a temporary lull of our tortures, for the interiors of the inns are like the exteriors of the natives, swarming with this species of animated creation.

It is said that once, when these tormentors were filled with an unanimous desire, an unsuspecting traveller was dragged bodily from his bed! This needs confirmation. One word more, and I have done with this vile subject. We returned from our ablutions, and found the Frenchmen engaged in conversation. “Ah!” said old Sémiond, “as to fleas, I don’t pretend to be different from anyone else—I have them.” This time he certainly spoke the truth.

We got down to La Ville in good time, and luxuriated there for several days; played many games of bowls with the natives, and were invariably beaten by them. At last it was necessary to part, and I walked southwards towards Monte Viso, while Macdonald went to Briançon.

While I have not attempted to conceal that the ascent of Mont Pelvoux is of a rather monotonous character, the view from its summit may be confidently recommended. A glance at the map will show that, with the single exception of Monte Viso, it is better situated than any other mountain of considerable height for viewing the Western Alps.

Our discovery that the peak which is now called the Pointe des Écrins was a separate and distinct mountain from Mont Pelvoux—and not its highest point—gave us satisfaction, although it was also rather of the nature of a disappointment.

On our return to La Bessée we wrongly identified it with the peak which is seen from that place on the left of Mont Pelvoux. The two mountains bear a considerable resemblance to each other, so the mistake is not, perhaps, unpardonable. The latter mountain is considerably higher than the Wetterhorn or Monte Viso, it has no name; we called it the Pic Sans Nom.

It has been observed that it is improbable the French surveyors would have remained for several days upon the Pic de la Pyramide without visiting the loftier and true summit of Mont Pelvoux. If they did, it is strange that they did not leave some memorial of their visit. The natives who accompanied them asserted that they did not pass from one to the other, and we therefore claimed to have made the ascent of the loftiest point for the first time. The claim, however, cannot be sustained, on account of the ascent of M. Puiseux. It is a matter of little moment; the excursion had for us all the interest of a first ascent; and I look back upon this, my first serious mountain scramble, with more satisfaction, and with as much pleasure as upon any that is recorded in this volume.

After parting from my agreeable companions, I walked by the gorge of the Guil to Abriès, and made the acquaintance at that place of an ex-harbour-master of Marseilles—a genial man, who spoke English well. Besides the ex-harbour-master and some fine trout in the neighbouring streams, there was little to invite a stay at Abriès. The inn—l’Étoile, chez Richard—is a place to be avoided. Richard, it may be observed, possessed the instincts of a robber. At a later date, when forced to seek shelter in his house, he desired to see my passport, and, catching sight of the words John Russell, he entered that name instead of my own in a report to the gendarmerie, uttering an exclamation of joyful surprise at the same time. I foolishly allowed the mistake to pass, and had to pay dearly for it; for he made out a lordly bill, against which all protest was unavailing.

His innocent and not very extraordinary mistake was eclipsed by a gendarme of Bourg d’Oysans, who took the passport, gravely held it upside down for several minutes, pretended to read it, and handed it back, saying it was all right.

Round about Abriès the patois of the district is more or less Italian in character, and the pronunciation of the natives reminds one of a cockney who attempts to speak French for the first time. Here bread is pronounced pane, and cheese, fromargee. There are a considerable number of dialects in use in this corner of France; and sometimes in the space of only a few miles one can find several, which are almost as unintelligible to the natives of the surrounding districts as they are to the traveller. In some districts the spelling of the patois is the same, but the pronunciation is different—in this resembling Chinese. It is not easy for the stranger to understand these dialects, either written or spoken; and this will be readily perceived from the samples given in the note, which are different versions of the parable of the prodigal son.27

I quitted the abominations of Abriès to seek a quiet bundle of hay at Le Chalp—a village some miles nearer to Monte Viso. On approaching the place the odour of sanctity28 became distinctly perceptible; and on turning a corner the cause was manifested—there was the priest of the village, surrounded by some of his flock. I advanced humbly, hat in hand, but almost before a word could be said, he broke out with, “Who are you?” “What are you?” “What do you want?” I endeavoured to explain. “You are a deserter; I know you are a deserter; go away, you can’t stay here; go to Le Monta, down there; I won’t have you here,” and he literally drove me away. The explanation of his strange behaviour was that Piedmontese soldiers who were tired of the service had not unfrequently crossed the Col de la Traversette into the valley, and trouble had arisen from harbouring them. However, I did not know this at the time, and was not a little indignant that I, who was marching to the attack, should be taken for a deserter.

So I walked away, and shortly afterwards, as it was getting dark, encamped in a lovely hole—a cavity or kind of basin in the earth, with a stream on one side, a rock to windward, and some broken branches close at hand. Nothing could be more perfect: rock, hole, wood, and water. After making a roaring fire, I nestled in my blanket bag (an ordinary blanket sewn up double round the legs, with a piece of elastic ribbon round the open end), and slept, but not for long. I was troubled with dreams of the Inquisition; the tortures were being applied—priests were forcing fleas down my nostrils and into my eyes—and with red-hot pincers were taking out bits of flesh, and then cutting off my ears and tickling the soles of my feet. This was too much; I yelled a great yell and awoke, to find myself covered with innumerable crawling bodies. They were ants. I had camped by an anthill, and, after making its inhabitants mad with the fire, had coolly lain down in their midst.

The night was fine, and as I settled down in a neighbouring hole, a brilliant meteor sailed across full sixty of the cloudless sky, leaving a trail of light behind which lasted for several seconds. It was the herald of a splendid spectacle. Stars fell by hundreds; and not dimmed by intervening vapours, they sparkled with greater brightness than Sirius in our damp climate.

The next morning, after walking up the valley to examine Monte Viso, I returned to Abriès, and engaged a man from a neighbouring hamlet, for whom the ex-harbour-master had sent; an inveterate smoker, and thirsty in proportion, whose pipe never left his mouth except to allow him to drink. We returned up the valley together, and slept in a hut of a shepherd, whose yearly wage was almost as small as that of the herdsman spoken of in Hyperion by Longfellow; and the next morning, in his company, proceeded to the summit of the pass which I had crossed in . We were baffled in our attempt to get closer to the mountain. A deep notch29 with precipitous cliffs cut us off from it. The snow-slope, too, which existed in the preceding year on the Piedmontese side of the pass, was now wanting, and we were unable to descend the rocks which lay beneath. A fortnight afterwards the mountain was, however, ascended for the first time by Messrs. Mathews and Jacomb, with the two Croz’s of Chamounix. Their attempt was made from the southern side, and the ascent, which was formerly considered a thing totally impossible, has become one of the most common and favourite excursions of the district.

We returned crestfallen to Abriès. The shepherd, whose boots were very much out of repair, slipped upon the steep snow-slopes, and performed wonderful and alarming gyrations, which took him to the bottom of the valley more quickly than he could otherwise have descended. He was not much hurt, and was made happy by a few needles and a little thread to repair his abraded garments. The other man, however, considered it wilful waste to give him brandy to rub in his cuts, when it could be disposed of in a more ordinary and pleasant manner.

The night of the found me at St. Veran, a village made famous by Neff, but in no other respect remarkable, saving that it is supposed to be the highest in Europe.30 The Protestants now form only a miserable minority; in there were said to be 120 to 780 Catholics. The poor inn was kept by one of the former, and it gave the impression of great poverty. There was no meat, no bread, no butter or cheese, and almost the only things that could be obtained were eggs. The bill for supper, bed, and breakfast, amounted to one and sevenpence.

In this neighbourhood, and indeed all round about Monte Viso, the chamois still remain in considerable numbers. They said at St. Veran that six had been seen from the village on the day I was there, and the innkeeper declared that he had seen fifty together in the previous week! I myself saw in this and in the previous season several small companies round about the Viso. It is perhaps as favourable a district as any in the Alps for a sportsman who wishes to hunt the chamois, as the ground over which they wander is by no means of excessive difficulty.

The next day I descended the valley to Ville Vieille, and passed near the village of Molines, on the opposite side of the valley, a remarkable natural pillar, in form not unlike a champagne bottle, about seventy feet high, which had been produced by the action of the weather, and, in all probability, chiefly by rain. In this case a “block of euphotide or diallage rock protects a friable limestone.”31 The contrast of this dark cap with the white base, and the singularity of the form, made it a striking object. These natural pillars are among the most remarkable examples of the potent effects which can be produced by long-continued action of quiet-working forces. They are found in several other places in the Alps,32 as well as elsewhere.

The village of Ville Vieille boasts of an inn with the sign of the Elephant; which, in the opinion of local amateurs, is a proof that Hannibal passed through the gorge of the Guil. I remember the place, because its bread, being only a month old, was unusually soft; and, for the first time during ten days, it was possible to eat some, without first of all chopping it into small pieces and soaking it in hot water, which produced a slimy paste on the outside, but left a hard untouched kernel.

The same day I crossed the Col Isoard to Briançon. It was the , and all the world was en fête; sounds of revelry proceeded from the houses of Servières as I passed over the bridge upon which the pyrrhic dance is annually performed,33 and natives in all degrees of inebriation staggered about the paths. It was late before the lights of the great fortress came into sight; but unchallenged I passed through its gates, and once more sought shelter under the roof of the Hôtel de l’Ours.34