C

Subsequent History of the Matterhorn398

The Val Tournanche natives who started to facilitate the way up the southwest ridge of the Matterhorn for MM. Giordano and Sella, pitched their tent upon my third platform, at the foot of the Great Tower (12,992 feet), and enjoyed several days of bad weather under its shelter. On the first fine day () they began their work, and about midday on the got on to the “shoulder,” and arrived at the base of the final peak (the point where Bennen stopped on ). The counsels of the party were then divided. Two—Jean-Antoine Carrel and Joseph Maquignaz—wished to go on; the others were not eager about it. A discussion took place, and the result was they all commenced to descend, and whilst upon the “cravate” (13,524) they heard our cries from the summit.399 Upon the they went down to Breuil and reported their ill-success to M. Giordano (see Chapter XXI). That gentleman was naturally much disappointed, and pressed the men to set out again.400 Said he, “Until now I have striven for the honour of making the first ascent—fate has decided against me—I am beaten. Patience! Now, if I go to any further expense, it will be on your account, for your honour, and for your interests. Will you start again to settle the question, or, at least, to let there be no more uncertainty?” The majority of the men (in fact the whole of them with the exception of Jean-Antoine) refused point-blank to have anything more to do with the mountain. Carrel, however, stepped forward, saying, “As for me, I have not given it up; if you (turning to the Abbé Gorret) or the others will come, I will start again immediately.” “Not I!” said one. “No more for me,” cried a second. “If you would give me a thousand francs I would not go back,” said a third. The Abbé Gorret alone volunteered. This plucky priest was concerned in the very first attempts upon the mountain,401 and is an enthusiastic mountaineer. Carrel and the Abbé would have set out by themselves had not J. B. Bich and J.-A. Meynet (two men in the employ of Favre the innkeeper) come forward at the last moment. M. Giordano also wished to accompany them, but the men knew the nature of the work they had to undertake, and positively declined to be accompanied by an amateur.

These four men left Breuil at 6:30 a.m. on , at 1 p.m. arrived at the third tent-platform, and there passed the night. At daybreak on the they continued the ascent by the route which had been taken before; passed successively the Great Tower, the Crête du Coq, the “cravate,” and the “shoulder,”402 and at 10 a.m. gained the point at the foot of the final peak from which the explorers had turned back on the .403 They had then about 800 feet to accomplish, and, says the Abbé, “nous allions entrer en pays inconnu, aucun n’étant jamais allé aussi loin.”

The passage of the cleft which stopped Bennen was accomplished, and then the party proceeded directly towards the summit, over rocks which for some distance were not particularly difficult. The steep cliffs down which we had hurled stones (on the ) then stopped their way, and Carrel led round to the left or Z’Mutt side. The work at this part was of the very greatest difficulty, and stones and icicles which fell rendered the position of the party very precarious;404 so much so that they preferred to turn up directly towards the summit, and climb by rocks that the Abbé termed “almost perpendicular.” He added, “This part occupied the most time, and gave us the greatest trouble.” At length they arrived at a fault in the rocks which formed a roughly horizontal gallery. They crept along this in the direction of a ridge that descended towards the northwest, or thereabouts, and when close to the ridge, found that they could not climb on to it; but they perceived that, by descending a gully with perpendicular sides, they could reach the ridge at a lower point. The bold Abbé was the heaviest and the strongest of the four, and he was sacrificed for the success of the expedition. He and Meynet remained behind, and lowered the others, one by one, into the gully. Carrel and Bich clambered up the other side, attained the ridge descending towards the northwest, shortly afterwards gained an “easy route,405 they galloped,” and in a few minutes reached the southern end of the summit-ridge.

The time of their arrival does not appear to have been noticed. It was late in the day, I believe about 3 p.m. Carrel and his comrade only waited long enough to plant a flag by the side of the cairn that we had built three days previously, then descended at once, rejoined the others, and all four hurried down as fast as possible to the tent. They were so pressed for time that they could not eat! and it was 9 p.m. before they arrived at their camp at the foot of the Great Tower. In descending they followed the gallery above mentioned throughout its entire length, and so avoided the very difficult rocks over which they had passed on the ascent. As they were traversing the length of the “shoulder” they witnessed the phenomenon to which I have already adverted in note 380.

When Carrel and Bich were near the summit they saw our traces upon the Matterhorngletscher, and suspected that an accident had occurred; they did not, however, hear of the Matterhorn catastrophe until their return to Breuil, at 3 p.m. upon the . The details of that sad event were in the mouths of all, and it was not unnaturally supposed, in the absence of correct information, that the accident was a proof that the northern side was frightfully dangerous. The safe return of the four Italians was regarded, on the other hand, as evidence that the Breuil route was the best. Those who were interested (either personally or otherwise) in the Val Tournanche made the most of the circumstances, and trumpeted the praises of the southern route. Some went farther, and instituted comparisons between the two routes to the disadvantage of the northern one, and were pleased to term our expedition on the – precipitate, and so forth. Considering the circumstances which caused us to leave the Val Tournanche on the , these remarks were not in the best possible taste, but I have no feeling regarding them. There may be some, however, who may be interested in a comparison of the two routes, and for their sakes I will place the essential points in juxtaposition. We (that is the Taugwalders and myself) were absent from Zermatt 53 hours. Excluding halts and stoppages of one sort or another, the ascent and descent occupied us 23 hours. Zermatt is 5,315 feet above the level of the sea, and the Matterhorn is 14,780; we had therefore to ascend 9,465 feet. As far as the point marked 10,820 feet the way was known, so we had to find the way over only 3,960 feet. The members of our party (I now include all) were very unequal in ability, and none of us could for a moment be compared as cragsmen with Jean-Antoine Carrel. The four Italians who started from Breuil on the were absent during 56½ hours, and as far as I can gather from the published account, and from conversation with the men, excluding halts, they took for the ascent and descent 23¾ hours. The hotel at Gioment is 6,890 feet above the sea, so they had to ascend 7,890 feet. As far as the end of the “shoulder” the way was known to Carrel, and he had to find the way over only about 800 feet. All four men were born mountaineers, good climbers, and they were led by the most expert cragsman I have seen. The weather in each instance was fine. It is seen, therefore, that these four nearly equally matched men took a longer time to ascend 1,500 feet less height than ourselves, although we had to find the way over more than four times as much untrodden ground as they. This alone would lead any mountaineer to suppose that their route must have been more difficult than ours.406 I know the greater part of the ground over which they passed, and from my knowledge, and from the account of Mr. Grove, I am sure that their route was not only more difficult, but that it was much more difficult, than ours.

This was not the opinion in the Val Tournanche at the end of , and the natives confidently reckoned that tourists would flock to their side in preference to the other. It was, I believe, the late Canon Carrel of Aosta (who always took great interest in such matters) who first proposed the construction of a cabane upon the southern side of the Matterhorn. The project was taken up with spirit, and funds for its execution were speedily provided—principally by the members of the Italian Alpine Club, or by their friends. The indefatigable Carrel found a natural hole upon the ledge called the “cravate” (13,524), and this, in course of time, was turned, under his direction, into a respectable little hut. Its position is superb, and gives a view of the most magnificent character.

Whilst this work was being carried out, my friend Mr. F. Craufurd Grove consulted me respecting the ascent of the Matterhorn. I recommended him to ascend by the northern route, and to place himself in the hands of Jean-Antoine Carrel. Mr. Grove found, however, that Carrel distinctly preferred the southern side, and they ascended accordingly by the Breuil route. Mr. Grove has been good enough to supply the following account of his expedition. He carries on my description of the southern route from the highest point I attained on that side (a little below the “cravate”) to the summit, and thus renders complete my descriptions of the two sides.

“In I ascended the Matterhorn from Breuil, taking as guides three mountaineers of the Valtournanche—J.-A. Carrel, J. Bich, and S. Meynet—Carrel being the leader. At that time the Matterhorn had not been scaled since the famous expedition of the Italian guides mentioned above.

“Our route was identical with that which they followed in their descent when, as will be seen, they struck out on one part of the mountain a different line from that which they had taken in ascending. After gaining the Col du Lion, we climbed the southwestern or Breuil arête by the route which has been described in these pages, passing the night at the then unfinished hut constructed by the Italian Alpine Club on the ‘cravate.’ Starting from the hut at daylight, we reached at an early hour the summit of the ‘shoulder,’ and then traversed its arête to the final peak of the Matterhorn. The passage of this arête was perhaps the most enjoyable part of the whole expedition. The ridge, worn by slow irregular decay into monstrous and rugged battlements, and guarded on each side by tremendous precipices, is grand beyond all description, but does not, strange to say, present any remarkable difficulty to the climber, save that it is exceedingly trying to the head. Great care is of course necessary, but the scramble is by no means of so arduous a nature as entirely to absorb the attention; so that a fine climb, and rock scenery, of grandeur perhaps unparalleled in the Alps, can both be appreciated.

“It was near the end of this arête, close to the place where it abuts against the final peak, that Professor Tyndall’s party turned in ,407 arrested by a cleft in the ridge. From the point where they stopped the main tower of the Matterhorn rises in front of the climber, abrupt, magnificent, and apparently inaccessible. The summit is fully 750 feet in vertical height above this spot, and certainly, to my eye, appeared to be separated from me by a yet more considerable interval; for I remember, when at the end of the arête, looking upward at the crest of the mountain, and thinking that it must be a good 1,000 feet above me.

“When the Italian guides made their splendid ascent, they traversed the arête of the shoulder to the main peak, passed the cleft which has been mentioned (see Chapter VI), clambered on to the tremendous northwestern face of the mountain (described by Mr. Whymper in Chapter XXI and note 371), and then endeavoured to cross this face so as to get on to the Z’Mutt arête.408 The passage of this slope proved a work of great difficulty and danger. I saw it from very near the place which they traversed, and was unable to conceive how any human creatures managed to crawl over rocks so steep and so treacherous. After they had got about halfway across, they found the difficulties of the route and the danger from falling stones so great, that they struck straight up the mountain, in the hope of finding some safer way. They were to a certain extent successful, for they came presently to a small ledge, caused by a sort of fault in the rock, running horizontally across the northwestern face of the mountain a little distance below the summit. Traversing this ledge, the Italians found themselves close to the Z’Mutt arête, but still separated from it by a barrier, to outflank which it was necessary to descend a perpendicular gully. Carrel and Bich were lowered down this, the other two men remaining at the top to haul up their companions on their return, as otherwise they could not have got up again. Passing on to the Z’Mutt arête without further difficulty, Carrel and Bich climbed by that ridge to the summit of the mountain. In returning, the Italians kept to the ledge for the whole distance across the northwestern face, and descended to the place where the arête of the shoulder abuts against the main peak by a sort of rough ridge of rocks between the northwestern and southern faces. When I ascended in , we followed this route in the ascent and in the descent. I thought the ledge difficult, in some places decidedly dangerous, and should not care to set foot on it again; but assuredly it neither is so difficult nor so continuously dangerous as those gaunt and pitiless rock-slopes which the Italians crossed in their upward route.

“The credit of making the Italian ascent of the Matterhorn belongs undoubtedly to J.-A. Carrel and to the other mountaineers who accompanied him. Bennen led his party bravely and skilfully to a point some 750 feet below the top. From this point, however, good guide though he was, Bennen had to retire defeated; and it was reserved for the better mountain-craft of the Valtournanche guide to win the difficult way to the summit of the Matterhorn.”

Mr. Craufurd Grove was the first traveller who ascended the Matterhorn after the accident, and the natives of Val Tournanche were, of course, greatly delighted that his ascent was made upon their side. Some of them, however, were by no means well pleased that J.-A. Carrel was so much regarded. They feared, perhaps, that he would acquire the monopoly of the mountain. Just a month after Mr. Grove’s ascent, six Valtournanchians set out to see whether they could not learn the route, and so come in for a share of the good things which were expected to arrive. They were three Maquignaz’s, Caesar Carrel (my old guide), J.-B. Carrel, and a daughter of the last named! They left Breuil at 5 a.m. on , and at 3 p.m. arrived at the hut, where they passed the night. At 7 a.m. the next day they started again (leaving J.-B. Carrel behind), and proceeded along the “shoulder” to the final peak; passed the cleft which had stopped Bennen, and clambered up the comparatively easy rocks on the other side until they arrived at the base of the last precipice, down which we had hurled stones on . They (young woman and all) were then about 350 feet from the summit! Then, instead of turning to the left, as Carrel and Mr. Grove had done, Joseph and J.-Pierre Maquignaz paid attention to the cliff in front of them, and managed to find a means of passing up, by clefts, ledges, and gullies, to the summit. This was a shorter (and it appears to be an easier) route than that taken by Carrel and Grove, and it has been followed by nearly all those who have since then ascended the mountain from the side of Breuil.410 Subsequently, ropes were fixed over the most difficult portions of the final climb.

In the meantime they had not been idle upon the other side. A hut was constructed upon the eastern face, at a height of 12,526 feet above the sea, near to the crest of the ridge which descends towards Zermatt (northeast ridge).411 The erection was undertaken by the Knubels, of St. Nicholas, at the expense of Monsieur Alex. Seiler and of the Swiss Alpine Club. This hut upon the east face is placed in an insecure position, and is now seldom used, as another hut or cabane has been built upon the Hörnli ridge,412 a few yards to the east of, and slightly lower down than the spot where Mr. Kennedy put up his cairn in (see Chapter V).

The second ascent of the Matterhorn from the northern side was made by Mr. J. M. Elliot, on –, with the guides Joseph Marie Lochmatter and Peter Knubel. Since then very numerous ascents have been made both upon the Swiss and upon the Italian side. Down to the end of they were equally divided between the northern (or Zermatt) and the southern (or Breuil) route. Until that time, neither guides nor tourists had got clear of the idea that the Swiss route was more difficult and dangerous than the Italian one. In (the year following the publication of Scrambles Amongst the Alps) the Zermatt side found more favour, and it has continued to be the popular route to the present time. In Appendix E the ascents have been tabulated down to the first which was made in ;413 and, amongst the 194 which are enumerated, 136 were made on the Swiss side, against 23 on the Italian side. On nine other occasions persons crossed the mountains from Zermatt to Breuil, and upon twenty-two more traversed it from Breuil to Zermatt.

Prof. Tyndall was the first to turn the summit of the Matterhorn into a pass (see Appendix E, ascent No. 7). He went up the Breuil side and came down upon Zermatt. A few days later Messrs. Hoiler and Thioly crossed the mountain in the reverse direction (No. 8).

The first of the following ascents which calls for notice is that by Signor F. Giordano (No. 13). This gentleman came to Breuil several times after his visit in , but he was always baffled by the weather. In , he got as high as the “cravate” with Jean-Antoine Carrel and other men, and was detained there five days and nights unable to move either up or down! At last, on –, he was able to gratify his desire, and accomplished the feat of ascending the mountain upon one side and descending it upon the other. Signor Giordano spent a considerable time in examining the structure of the Matterhorn, and became benighted upon its eastern face in consequence. I am indebted to him for the valuable note and the accompanying section which follow the Table of Ascents.414

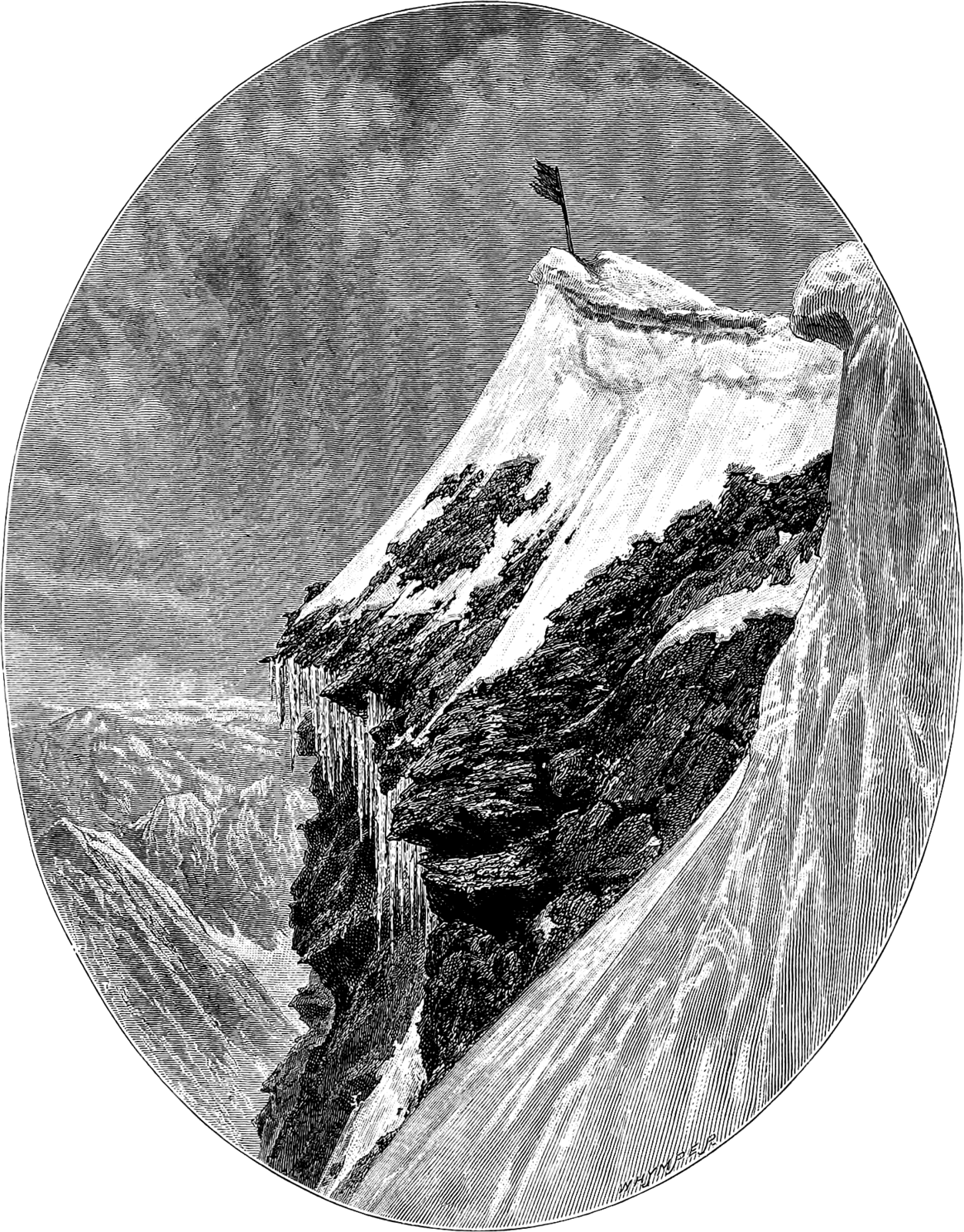

Questions having been frequently put to me respecting the immediate summit of the Matterhorn, and difficulties having been expressed as to recognition of the two views given in Chapter XXI (here and here), I made an ascent of the mountain in , to photograph the summit, and to see what changes had occurred since our visit nine years before. The summits of most high mountains vary from time to time, and the Matterhorn is no exception to the general rule. It was sharper and narrower in than in . Instead of being able “to run about,” every step had to be cut with the axe; and the immediate summit, instead of being a blunt and rounded eminence, was a little cone of snow which went to a sharp point. In consequence of a strong north wind which was blowing at the time, we had to work down upon the edge of the cliff overlooking Breuil, to get protection for the camera, and eventually we gained a position which gave a good view of the summit; but our ledge was so small that we could not venture to unrope, and Jean-Antoine had to squat down whilst I photographed over his head. The engraving shown earlier in this chapter has been made from the photograph which was taken on this occasion. The nearest of the lower peaks, on the left, is the summit of the Dent d’Hérens.

Carrel and I stopped a second night at the cabane on the east face, and whilst there we had the insecurity of its position forcibly impressed upon us by seeing a huge block break away from the rock at its side, and go crashing down over the very route which is commonly pursued by tourists. The view from this hut extends from the Bietschorn on the north to the Grand Tournalin in the south, and includes the Mischabel group, the Allaleinhorn, Alphubel, Rimpfischhorn and Strahlhorn, Monte Rosa, the Lyskamm and the Breithorn. The uppermost 800 feet of the Matterhorn can be seen from the hut, but the rest of the intervening part of the mountain is not visible, being hidden by a small ridge which projects from the face.

In two deaths occurred upon the Matterhorn, within a few hours of each other—one in the hut on the “cravate,” and the second upon the eastern face. On , Dr. C. Lüscher and Prof. H. Schiess started from Breuil at a very early hour, accompanied by the guides Joseph Marie Lochmatter, Joseph Brantschen, and P. Beytrison. They gained the hut on the “cravate” (13,524 feet) at 1:20 p.m., and stopped there for the night; and on the following day the party crossed the summit of the mountain, with the exception of Brantschen, who was left behind in the hut, some say only slightly ill, and others at the point of death. They sent back assistance to their sick comrade in a somewhat tardy fashion, and when the relief party arrived at the hut Brantschen was found dead. Dr. Lüscher and Prof. Schiess furnished an account of what happened to the Basel Section of the Swiss Alpine Club, and from this statement the following extracts are made.

“When we reached the ‘cravate’ it was already 1 p.m. Lochmatter told us we had still four hours’ work to reach the top, and the question arose whether it would not be more prudent to spend the night in the Italian cabane. … In the course of the afternoon we remarked that Brantschen was unwell; Lochmatter kept on pressing him to eat and drink. We took no great heed of the matter, and looked on it as mountain-sickness, or the result of drinking too much water during the ascent. On my asking Brantschen when he had first felt unwell, he answered, since he had slept in the sun. We observed no spitting of blood on his part during the ascent; had we noticed anything of the kind we should naturally not have taken him with us. Up to 5 p.m. he was sitting on the doorstep, his gaze directed on Breuil. Later on, after he had lain down, he began to groan and to throw himself about, in the night also to rattle in the throat. Being asked where he felt pain, he answered, he felt pains all over. There was altogether not much to be got out of him either by us or by Lochmatter. He was, however, in no high state of fever, he was not hot to the touch, and his pulse was not unusually rapid. There was no remarkable coughing. My guide acted as cook, and succeeded with the small stock of wood in making tea several times, and towards morning chocolate also. This tea was the only restorative we could offer to the sick man, and he seemed to take it gladly. Towards morning he at last became quieter, his breathing more regular, and he left off groaning and crying out.

“On the morning of the guides had given a hope that Brantschen might recover sufficiently to accompany us; for this reason the start was delayed to 6 o’clock. But it became evident that this was impossible. And now no discussion took place, neither was there any interchange of plans between the guides and Brantschen. It appeared best to all of us to wrap up Brantschen well, to furnish him with the necessary provisions, and to hurry over quickly to Zermatt and send him help. Had we remained with him it would have been no benefit to Brantschen; and I am also convinced that he himself thought our course of action perfectly natural, otherwise he would have made some remonstrance, which he did not do. We bade him keep up his courage and wished him farewell, in the hope that he would by degrees entirely recover. … At 1:30 a.m. on we reached Zermatt. We had sent from the Swiss hut a message before us, and at 3 o’clock the relief party started over the Furgggletscher skirting the Matterhorn. It found Brantschen already dead and stiff; apparently a rupture of the heart or lungs had happened.”415

At the time that this was taking place on the South side of the Matterhorn, Dr. William O. Moseley of Boston lost his life on the East Face. He left Zermatt at 10:30 p.m. on , in company with Mr. A. E. Craven and the guides Peter Rubi and Christian Inabnit; and ascended the mountain by the usual northern route, without stopping at the hut. They reached the summit at 9 a.m. on the , and had returned to within a short distance from the hut, when Dr. Moseley (who had found it irksome to be tied up, and had frequently wished to go unroped) untied himself from the rest, doing so entirely upon his own responsibility. A few minutes later the party had to cross a projecting piece of rock. Rubi went over first, and planted his axe in position to give firm footing to Dr. Moseley, who followed. But, unhappily, he declined assistance; placed his hand upon the rock, and endeavoured to vault over it. In doing so he slipped, lost hold of his axe, and fell with ever-accelerating velocity down the East Face for about 2,000 feet, and of course was killed on the spot. His body was recovered three days later and was interred under the south wall of the English Church at Zermatt. “I was shocked to find,” said a friend who examined his remains, “that Dr. Moseley had hardly any nails in one of his boots.”

Many persons have talked at different times about the possibility of finding a way up the Matterhorn from the side of the Z’Mutt Glacier; but it was not until the year that a way was discovered. On –, Mr. A. F. Mummery with the guides Alexander Burgener, Petrus, and Kentinetta succeeded in gaining the summit by first going up the long snow-buttress which runs out from the mountain towards the northwest, and then up the rocks above. When nearing the top, they joined the routes taken by Carrel and Mr. Grove upon the first ascents which were made on the Italian side.416

At the very time that Mr. Mummery was engaged in his expedition, Mr. W. Penhall with the guides Ferdinand Imseng and Louis Zurbrücken, was occupied on a similar enterprise, and also ascended the Matterhorn from the direction of the Stockhi. Mr. Penhall, however, at first took a course slightly more to the south than Mr. Mummery, though he, at last, like the others, got on to the main Z’Mutt arête, and completed the ascent by following a portion of the old Italian route.417

Three days afterwards (–), Mr. J. Baumann followed in Mr. Mummery’s footsteps. “I found it,” he said, “an interesting rock-climb, presenting no extraordinary difficulties. … I am of opinion that this ascent by the Z’Mutt arête will in future become the favourite way of crossing the Matterhorn.”418 As yet, Mr. Baumann’s anticipation has not been realised.419

In , another life was lost on the East Face. Two friends, named Borckhardt and Davies, resolved to climb the mountain. We knew, said the latter, that it had been done by ladies and youths. “It was the regular thing to go up the Matterhorn, and we accordingly determined to make the ascent.”

Accompanied by Fridolin Kronig and Peter Aufdemblatten, they left Zermatt on , in fine weather; and at 3 a.m. on the started from the hut on the Hörnli ridge, arriving on the summit at about 9 a.m. The comparative rapidity with which they mounted was probably due to the fact that they were closely following in the track of other parties of tourists. The weather changed during the early morning, and it began to hail while they were still on the top. They commenced to descend at 9:20 a.m., in the next ten hours came down scarcely 2,000 feet, and were benighted some distance above the old hut on the East Face. All tracks on the mountain were obliterated by the hail and snow which fell. They remained on this spot from about 7 p.m. on the until 1 p.m. on the , and then Mr. Davies and the two guides continued the descent, leaving Mr. Borckhardt behind, upon the open face of the mountain, lying in a helpless condition, at the point of death! A few hours later he was found dead and stiff, partly covered by freshly-fallen snow.

The entire story exceeds in horror and incredibility the abandonment of Brantschen, and is much too long to recount in these pages.420 An inquiry into this miserable business was held by the Valaisan authorities, and in an official Report upon it by Prof. F. O. Wolf, which was published at Sion, it is said “that the sole causes of the accident were the sudden changes in the weather; the insufficient number of guides; and the facts that neither Mr. Davies nor Mr. Borckhardt were fit to climb such a peak, were insufficiently clad, and badly provisioned.” A further cause might have been added, namely, the incapacity of the guides.

In , there was yet another accident upon the East Face, which caused the loss of an entire party. A young man from Strasburg, Herr Goehrs, started from the hut on the Hörnli ridge at 3:30 a.m. on the , with two young guides, Alois Graven and Joseph Brantschen. They were shortly followed by several other persons. About 9 a.m., both parties encountered high wind when a thousand feet or so below the summit, and decided to return. Very soon afterwards, Fridolin Burgener (one of the guides of the lower party) heard a clatter, and saw Herr Goehrs and his guides flying through the air within a hundred yards of him. The three fell until they were brought up on the Furgggletscher, and of course were killed outright. Though the cause of this accident is unknown, the probability is that these three very young men (who could not have had adequate mountaineering experience) were killed through one or more of them slipping upon the easiest side of the mountain. Since this last lamentable affair the Zermatt face of the Matterhorn has been free from disaster, but there still remain to be mentioned two catastrophes which have occurred upon the Italian side.

When telegrams came in, at the beginning of , stating that Jean-Antoine Carrel had died from fatigue on the south side of the Matterhorn, those who knew the man scarcely credited the report. It was not likely that this tough and hardy mountaineer would die from fatigue anywhere, still less that he would succumb upon “his own mountain.” But it was true. Jean-Antoine perished from the combined effects of cold, hunger, and fatigue upon his own side of his own mountain, almost within sight of his own home. He started on the from Breuil, with an Italian gentleman and Charles Gorret (brother of the Abbé Gorret), with the intention of crossing the Matterhorn in one day. The weather at the time of their departure was the very best, and it changed in the course of the day to the very worst. They were shut up in the cabane at the foot of the Great Tower during the , with scarcely any food, and on the retreated to Breuil. Although Jean-Antoine (upon whom, as leading guide, the chief labour and responsibility naturally devolved) ultimately succeeded in getting his party safely off the mountain, he himself was so overcome by fatigue, cold, and want of food that he died on the spot.

Jean-Antoine Carrel entered his sixty-second year in ,421 and was in the field throughout the summer. On , having just returned from an ascent of Mont Blanc, he was engaged at Courmayeur by Signor Leone Sinigaglia, of Turin, for an ascent of the Matterhorn. He proceeded to the Val Tournanche, and on the set out with him and Charles Gorret, for the last time, to ascend his own mountain by his own route. A long and clear account of what happened was communicated by Signor Sinigaglia to the Italian Alpine Club, and from this the following relation is condensed:—

“We started for the Cervin at 2:15 a.m. on the , in splendid weather, with the intention of descending the same night to the hut at the Hörnli on the Swiss side. We proceeded pretty well, but the glaze of ice on the rocks near the Col du Lion retarded our march somewhat, and when we arrived at the hut at the foot of the Great Tower, prudence counselled the postponement of the ascent until the next day, for the sky was becoming overcast. We decided upon this, and stopped.

“Here I ought to mention that both I and Gorret noticed with uneasiness that Carrel showed signs of fatigue upon leaving the Col du Lion. I attributed this to temporary weakness. As soon as we reached the hut he lay down and slept profoundly for two hours, and awoke much restored. In the meantime the weather was rapidly changing. Storm clouds coming from the direction of Mont Blanc hung over the Dent d’Hérens, but we regarded them as transitory, and trusted to the north wind, which was still continuing to blow. Meanwhile, three of the Maquignaz’s and Edward Bich, whom we found at the hut, returning from looking after the ropes, started downwards for Breuil, at parting wishing us a happy ascent, and holding out hopes of a splendid day for the morrow.

“But, after their departure, the weather grew worse very rapidly; the wind changed, and towards evening there broke upon us a most violent hurricane of hail and snow, accompanied by frequent flashes of lightning. The air was so charged with electricity that for two consecutive hours in the night one could see in the hut as in broad daylight. The storm continued to rage all night, and the day and night following, continuously, with incredible violence. The temperature in the hut fell to −3 degrees.

“The situation was becoming somewhat alarming, for the provisions were getting low, and we had already begun to use the seats of the hut as firewood. The rocks were in an extremely bad state, and we were afraid that if we stopped longer, and the storm continued, we should be blocked up in the hut for several days. This being the state of affairs, it was decided among the guides that if the wind should abate we should descend on the following morning; and, as the wind did abate somewhat, on the morning of the (the weather, however, still remaining very bad) it was unanimously settled to make a retreat.

“At 9 a.m. we left the hut. I will not speak of the difficulties and dangers in descending the arête to the Col du Lion, which we reached at 2:30 p.m. The ropes were half frozen; the rocks were covered with a glaze of ice, and fresh snow hid all points of support. Some spots were really as bad as could be, and I owe much to the prudence and coolness of the two guides that we got over them without mishap.

“At the Col du Lion, where we hoped the wind would moderate, a dreadful hurricane recommenced, and in crossing the snowy passages we were nearly suffocated by the wind and snow which attacked us on all sides.422 Through the loss of a glove, Gorret, half an hour after leaving the hut, had already got a hand frostbitten. The cold was terrible here. Every moment we had to remove the ice from our eyes, and it was with the utmost difficulty that we could speak so as to understand one another.

“Nevertheless, Carrel continued to direct the descent in a most admirable manner, with a coolness, ability, and energy above all praise. I was delighted to see the change, and Gorret assisted him splendidly. This part of the descent presented unexpected difficulties, and at several points great dangers, the more so because the tourmente prevented Carrel from being sure of the right direction, in spite of his consummate knowledge of the Matterhorn. At 11 p.m. (or thereabouts—it was impossible to look at our watches, as all our clothes were half frozen) we were still toiling down the rocks. The guides sometimes asked each other where they were; then we went forward again—to stop, indeed would have been impossible. Carrel at last, by marvellous instinct, discovered the passage up which we had come, and in a sort of grotto we stopped a minute to take some brandy.

“While crossing some snow we saw Carrel slacken his pace, and then fall two or three times to the ground. Gorret asked him what was the matter, and he said ‘nothing,’ but he went on with difficulty. Attributing this to fatigue through the excessive toil, Gorret put himself at the head of the caravan, and Carrel, after the change, seemed better, and walked well, though with more circumspection than usual. From this place a short and steep passage takes one down to the pastures, where there is safety. Gorret descended first, and I after him. We were nearly at the bottom when I felt the rope pulled. We stopped, awkwardly placed as we were, and cried out to Carrel several times to come down, but we received no answer. Alarmed, we went up a little way, and heard him say, in a faint voice, ‘Come up and fetch me, I have no strength left.’

“We went up and found that he was lying with his stomach to the ground, holding on to a rock, in a semiconscious state, and unable to get up or to move a step. With extreme difficulty we carried him up to a safe place and asked him what was the matter. His only answer was, ‘I know no longer where I am.’ His hands were getting colder and colder, his speech weaker and more broken, and his body more still. We did all we could for him, putting with great difficulty the rest of the cognac into his mouth. He said something, and appeared to revive, but this did not last long. We tried rubbing him with snow, and shaking him, and calling to him continually; but he could only answer with moans.

“We tried to lift him, but it was impossible—he was getting stiff. We stooped down, and asked in his ear if he wished to commend his soul to God. With a last effort he answered ‘Yes,’ and then fell on his back, dead, upon the snow.”

Such was the end of Jean-Antoine Carrel—a man who was possessed with a pure and genuine love of mountains; a man of originality and resource, courage and determination, who delighted in exploration. His special qualities marked him out as a fit person to take part in new enterprises, and I preferred him to all others as a companion and assistant upon my journey amongst the Great Andes of the Equator. Going to a new country, on a new continent, he encountered much that was strange and unforeseen; yet when he turned his face homewards he had the satisfaction of knowing that he left no failures behind him.423 After parting at Guayaquil in we did not meet again. In his latter years, I am told, he showed signs of age, and from information which has been communicated to me it is clear that he had arrived at a time when it would have been prudent to retire—if he could have done so. It was not in his nature to spare himself, and he worked to the very last. The manner of his death strikes a chord in hearts he never knew. He recognised to the fullest extent the duties of his position, and in the closing act of his life set a brilliant example of fidelity and devotion. For it cannot be doubted that, enfeebled as he was, he could have saved himself had he given his attention to self-preservation. He took a nobler course; and, accepting his responsibility, devoted his whole soul to the welfare of his comrades, until, utterly exhausted, he fell staggering on the snow. He was already dying. Life was flickering, yet the brave spirit said “It is nothing.” They placed him in the rear to ease his work. He was no longer able even to support himself; he dropped to the ground, and in a few minutes expired.424

I very much regret to have to mention yet another tragedy, which occurred quite recently. On , Andreas Seiler (one of the youngest members of the family of my old friend M. Alexandre Seiler) and Johann Biener of Zermatt lost their lives on the south side of the Matterhorn. Mr. Oscar Gysi, who was closely following them, has, at my request, furnished the following statement:—

“On , shortly before 6 a.m., we left the Lac Noir Hotel, crossed the Furggjoch, and on the Italian side joined the ordinary route from Breuil for the Matterhorn. There were five of us—Andreas Seiler, myself, and as guides Johann Biener (aged 24), Joseph Taugwalder (aged 27), and L. Moser of Taesch (aged 22). When about an hour below the Col du Lion we tied up—Seiler insisting upon being roped to Biener, with whom he had been climbing all the summer. Biener and Seiler were in advance, but we kept well together. When we were considerably higher than the Tête du Lion, and within about thirty minutes of the hut at the foot of the Great Tower, we came to an almost perpendicular chimney, some twenty feet high, down which a stout knotted rope hung. Biener and Seiler passed up it. We followed, and on arriving at the top Moser took off his sac to tie up afresh the wood that he carried. Seiler and Biener were impatient to reach the hut, and wished to proceed without us; but Taugwalder and Moser asked them to wait. Their words were, however, useless. Moser, who had warned Seiler repeatedly during the last half-hour to be careful, and who did not like their overconfidence, prayed Seiler to let him tie himself to their rope. Seiler and Biener, however, only laughed at him for his concern, and started off. Moser finished tying up his wood, and we went on. The others were only five minutes ahead, and we had reached a difficult spot, and were standing in steps cut at the top of a small patch of ice, at an angle of 50°, and close to rock, when Moser called out, ‘Beware of stones.’ We pressed up close to the rock and listened, when the two” (Seiler and Biener) “shot past us. We were all three close together, and Moser could have touched them with his axe. … I see them still—they were photographed in my mind. They were tied together. Seiler passed close to us, his back downwards, his head well bent up, as if he were preparing for a sudden shock. Biener flew far out against the blue sky, and the rope was stretched tightly between them.” They fell on to the Glacier du Lion, and when the bodies were recovered they were still tied together. “With both, the crown of the head was cut away as though it had been done by a sharp instrument. … Seiler’s watch was crushed, and his left boot was missing, although the foot was uninjured. How the accident happened will never be known, as no one saw them slip. I am inclined to think that Seiler was climbing at the same time as Biener, instead of waiting until he had found firm hold, and that the former slipped, jerking Biener off his feet. I am strengthened in this belief by the position of the two as I saw them fly past.”

Accidents of this nature, I apprehend, will recur, and may become more frequent than heretofore through the “facilitations,” the multiplication of cabanes, and increased vulgarisation of the mountain.

Routes up the Matterhorn.

The route which is now followed on the Northern (or Zermatt) side, so far as the foot of the final peak, is the same as that which was taken on the First Ascent; but there (about 800 feet below the summit), instead of bearing away on to the northern face (that overlooking the Matterhorngletscher), the tourist now clambers up directly towards the summit, by means of fixed ropes and chains.

After starting from Zermatt, the stream from the Z’Mutt Valley is crossed by a bridge which is commonly termed the Matterhorn bridge, and the new path to the Hotel at the Lac Noir is taken. This is a little shorter than the old path, which is more to the north. From the Lac Noir there is a path up to the Hörnli ridge, and this ridge is followed along its entire length right up to the foot of the Matterhorn. In passing from the end of the ridge on to the actual peak, the exact ledges are traversed over which I myself led upon the first ascent, and the track presently passes close to the spot where my tent was placed on –. The route then slightly descends (to turn the rib which is mentioned in Chapter XXI as intercepting the view of the eastern face from our tent-platform), and afterwards goes rather closer to the arête of the northeast ridge than we went in . We bore more away on to the east face, and proceeded more directly towards the foot of the final peak.

So long back as there was a strongly-marked track (amounting in some places to a path) along the Hörnli ridge and up the East Face to the cabane which was first erected;425 and little piles of stones, placed in prominent situations, pointed out the way even to the dullest person.

In , , and in , I revisited the tent-platform which was used on –. In the two former years the wall of stones which was built around the platform was still standing, and my initials were to be seen on the rock behind; but in I found it difficult to recognise the spot. By natural decay, the platform was nearly obliterated, and the inscribed rock had fallen down.426

On the southern side so much rock has broken away from the arête between the Col du Lion and the Great Tower that it is now possible to mount this ridge without passing through “the Chimney,” and I found at my last visit that the Chimney itself had partly disappeared.

With the exception of deviations that arise through such causes, the route which is now usually followed on the southern (or Breuil) side, is (so far as the foot of the final peak) the same as that which was taken upon the ascents by Jean-Antoine Carrel and Bich in , and by Mr. Craufurd Grove in . On the final five or six hundred feet several variations have been tried, some of which have already been mentioned.427 I was informed by J. B. Bich in , that there were at that time ropes fixed in no less than eight places upon this side of the mountain. The hut on the “cravate” still exists, and there is another at the foot of the Great Tower. A third one has been erected a few hundred feet below the base of the Great Tower, upon the position that was formerly occupied by my second tent-platform. A view of this cabane is given in my Guide to the Valley of Zermatt and the Matterhorn.

The Zermatt Railway.

The Zermatt railway, which was opened in , has rendered access more easy, and has largely increased the number of visitors. From a statement supplied to me by the Company, it appears that the railway carried 33,695 persons in , and 38,095 in . Since then, the traffic has increased very considerably.

The line runs from the Jura-Simplon station at Viège (Visp) to the northern end of Zermatt, and is 35 kilometres (or 22 miles nearly) in length. There are stations at Stalden, Kalpetran, St. Nicholas, Herbriggen, Randa and Taesch. The difference of level between Viège and Zermatt (3,200 feet) might have been overcome by a ruling gradient of 1 in 36. If anything like this had been employed, very heavy and costly works would have been necessary; but they have been avoided by adopting the Système Abt.428 Though short tunnels are numerous, there are no great cuttings or embankments on the Zermatt railway. The principal bridge crosses a torrent (Muhlebach) which falls into the Vispbach about halfway between Stalden and Kalpetran. This is 220 feet long, and 144 feet above the bottom of the ravine.

The Abt system aims at the avoidance of heavy works. Where the ground is flat the line skims the surface, and where there is an abrupt rise in the floor of the valley there are steep gradients upon which a third, cogged rail (crémaillère) is laid. The line presents therefore a succession of moderate inclines and very rapid ones. In some places the railway rises as much as one foot in eight. The third rail is not used when the gradients are less than one in forty, and is laid over only five miles. It is composed of two plates of steel which are bolted together in such a manner that the cogs alternate. The engines have two mechanisms—one for the ordinary rails and the other for the crémaillère. It is said that there are never less than four cogs or teeth biting at a time.429

Though the railway itself does not mar the beauty of the valley, it has worked mischief. The screech of the locomotives is out of harmony with the surroundings. Our clientele is different, say the hotelkeepers. Many of the old habitués have been driven away. Omnibuses rumble through “the” street, and cripples whining for alms invade the space which was once the Clubroom of Zermatt.

-

Mr. F. Craufurd Grove, President of the Alpine Club, –.

-

Mr. George E. Foster.

-

Rev. J. Robertson.

-

Mr. Frank Walker.

-

Mr. Leslie Stephen, President of the Alpine Club, –.

-

Mr. A. W. Moore.

-

Mr. Reginald S. Macdonald.

-

Mr. John Ball, Original Member, and first President of the Alpine Club.

-

Mr. William Mathews, Original Member, and President of the Alpine Club, –.

-

Mr. E. S. Kennedy, Original Member, and President of the Alpine Club, –.

-

Prof. T. G. Bonney, President of the Alpine Club, –.

-

Ulrich Lauener.

-

Prof. John Tyndall.

-

Mr. (Justice) Alfred Wills, Original Member, and President of the Alpine Club, –.

-

J.-Joseph Maquignaz.

-

Franz Andermatten.

-

Peter Taugwalder fils.

-

Peter Perrn.