IX

The Polar Journey

Come, my friends,

Tennyson, Ulysses

’Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Take it all in all it is wonderful that the South Pole was reached so soon after the North Pole had been conquered. From Cape Columbia to the North Pole, straight going, is 413 geographical miles, and Peary who took on his expedition 246 dogs, covered this distance in 37 days. From Hut Point to the South Pole and back is 1,532 geographical or 1,766 statute miles, the distance to the top of the Beardmore Glacier alone being more than 100 miles farther than Peary had to cover to the North Pole. Scott travelled from Hut Point to the South Pole in 75 days, and to the Pole and back to his last camp in 147 days, a period of five months.

A. C.-G.

(All miles are geographical unless otherwise stated.)

I

The Barrier Stage

The departure from Cape Evans at 11 p.m. on November 1 is described by Griffith Taylor, who started a few days later on the second Geological Journey with his own party:

“On the 31st October the pony parties started. Two weak ponies led by Atkinson and Keohane were sent off first at 4:30, and I accompanied them for about a mile. Keohane’s pony rejoiced in the name of Jimmy Pigg, and he stepped out much better than his fleeter-named mate Jehu. We heard through the telephone of their safe arrival at Hut Point.

“Next morning the Southern Party finished their mail, posting it in the packing case on Atkinson’s bunk, and then at 11 a.m. the last party were ready for the Pole. They had packed the sledges overnight, and they took 20 lbs. personal baggage. The Owner had asked me what book he should take. He wanted something fairly filling. I recommended Tyndall’s Glaciers—if he wouldn’t find it ‘coolish.’ He didn’t fancy this! So then I said, ‘Why not take Browning, as I’m doing?’ And I believe that he did so.

“Wright’s pony was the first harnessed to its sledge. Chinaman is Jehu’s rival for last place, and as some compensation is easy to harness. Seaman Evans led Snatcher, who used to rush ahead and take the lead as soon as he was harnessed. Cherry had Michael, a steady goer, and Wilson led Nobby—the pony rescued from the killer whales in March. Scott led out Snippets to the sledges, and harnessed him to the foremost, with little Anton’s help—only it turned out to be Bowers’ sledge! However he transferred in a few minutes and marched off rapidly to the south. Christopher, as usual, behaved like a demon. First they had to trice his front leg up tight under his shoulder, then it took five minutes to throw him. The sledge was brought up and he was harnessed in while his head was held down on the floe. Finally he rose up, still on three legs, and started off galloping as well as he was able. After several violent kicks his foreleg was released, and after more watch-spring flicks with his hind legs he set off fairly steadily. Titus can’t stop him when once he has started, and will have to do the fifteen miles in one lap probably!

“Dear old Titus—that was my last memory of him. Imperturbable as ever; never hasty, never angry, but soothing that vicious animal, and determined to get the best out of most unpromising material in his endeavour to do his simple duty.

“Bowers was last to leave. His pony, Victor, nervous but not vicious, was soon in the traces. I ran to the end of the Cape and watched the little cavalcade—already strung out into remote units—rapidly fade into the lonely white waste to southward.

“That evening I had a chat with Wilson over the telephone from the Discovery Hut—my last communication with those five gallant spirits.”181

All the ponies arrived at Hut Point by 4 p.m., just in time to escape a stiff blow. Three of them were housed with ourselves inside the hut, the rest being put into the verandah. The march showed that with their loads the speed of the different ponies varied to such an extent that individuals were soon separated by miles. “It reminded me of a regatta or a somewhat disorganized fleet with ships of very unequal speed.”182

It was decided to change to night marching, and the following evening we proceeded in the following order, which was the way of our going for the present. The three slowest ponies started first, namely, Jehu with Atkinson, Chinaman with Wright, James Pigg with Keohane. This party was known as the Baltic Fleet.

Two hours later Scott’s party followed; Scott with Snippets, Wilson with Nobby, and myself with Michael.

Both these parties camped for lunch in the middle of the night’s march. After another hour the remaining four men set to work to get Christopher into his sledge; when he was started they harnessed in their own ponies as quickly as possible and followed, making a nonstop run right through the night’s march. It was bad for men and ponies, but it was impossible to camp in the middle of the march owing to Christopher. The composition of this party was, Oates with Christopher, Bowers with Victor, Seaman Evans with Snatcher, Crean with Bones.

Each of these three parties was self-contained with tent, cooker and weekly bag, and the times of starting were so planned that the three parties arrived at the end of the march about the same time.

There was a strong head wind and low drift as we rounded Cape Armitage on our way to the Barrier and the future. Probably there were few of us who did not wonder when we should see the old familiar place again.

Scott’s party camped at Safety Camp as the Baltic fleet were getting underway again. Soon afterwards Ponting appeared with a dog sledge and a cinematograph—how anomalous it seemed—which “was up in time to catch the flying rearguard which came along in fine form, Snatcher leading and being stopped every now and again—a wonderful little beast. Christopher had given the usual trouble when harnessed, but was evidently subdued by the Barrier Surface. However, it was not thought advisable to halt him, and so the party fled through in the wake of the advance guard.”183

Immediately afterwards Scott’s party packed up. “Goodbye and good luck,” from Ponting, a wave of the hand not holding in a frisky pony and we had left the last link with the hut. “The future is in the lap of the gods; I can think of nothing left undone to deserve success.”184

The general scheme was to average 10 miles (11.5 statute) a day from Hut Point to One Ton Depot with the ponies lightly laden. From One Ton to the Gateway a daily average of 13 miles (15 statute) was necessary to carry twenty-four weekly units of food for four men each to the bottom of the glacier. This was the Barrier Stage of the journey, a distance of 369 miles (425 statute) as actually run on our sledge-meter. The twenty-four weekly units of food were to carry the Polar Party and two supporting parties forward to their farthest point, and back again to the bottom of the Beardmore, where three more units were to be left in a depot.185

All went well this first day on the Barrier, and encouraging messages left on empty petrol drums told us that the motors were going well when they passed. But the next day we passed five petrol drums which had been dumped. This meant that there was trouble, and some 14 miles from Hut Point we learned that the big end of the No. 2 cylinder of Day’s motor had broken, and half a mile beyond we found the motor itself, drifted up with snow, and looking a mournful wreck. The next day’s march (Sunday, November 5, a.m.) brought us to Corner Camp. There were a few legs down crevasses during the day but nothing to worry about.

From here we could see to the South an ominous mark in the snow which we hoped might not prove to be the second motor. It was: “the big end of No. 1 cylinder had cracked, the machine otherwise in good order. Evidently the engines are not fitted to working in this climate, a fact that should be certainly capable of correction. One thing is proved; the system of propulsion is altogether satisfactory.”186 And again: “It is a disappointment. I had hoped better of the machines once they got away on the Barrier Surface.”187

Scott had set his heart upon the success of the motors. He had run them in Norway and Switzerland; and everything was done that care and forethought could suggest. At the back of his mind, I feel sure, was the wish to abolish the cruelty which the use of ponies and dogs necessarily entails. “A small measure of success will be enough to show their possibilities, their ability to revolutionize polar transport. Seeing the machines at work today [leaving Cape Evans] and remembering that every defect so far shown is purely mechanical, it is impossible not to be convinced of their value. But the trifling mechanical defects and lack of experience show the risk of cutting out trials. A season of experiment with a small workshop at hand may be all that stands between success and failure.”188 I do not believe that Scott built high hopes on these motors: but it was a chance to help those who followed him. Scott was always trying to do that.

Did they succeed or fail? They certainly did not help us much, the motor which travelled farthest drawing a heavy load to just beyond Corner Camp. But even so fifty statute miles is fifty miles, and that they did it at all was an enormous advance. The distance travelled included hard and soft surfaces, and we found later when the snow bridges fell in during the summer that this car had crossed safely some broad crevasses. Also they worked in temperatures down to −30° F. All this was to the good, for no motor-driven machine had travelled on the Barrier before. The general design seemed to be right, all that was now wanted was experience. As an experiment they were successful in the South, but Scott never knew their true possibilities; for they were the direct ancestors of the “tanks” in France.

Night-marching had its advantages and disadvantages. The ponies were pulling in the colder part of the day and resting in the warm, which was good. Their coats dried well in the sun, and after a few days to get accustomed to the new conditions, they slept and fed in comparative comfort. On the other hand the pulling surface was undoubtedly better when the sun was high and the temperature warmer. Taking one thing with another there was no doubt that night-marching was better for ponies, but we seldom if ever tried it man-hauling.

Just now there was an amazing difference between day and night conditions. At midnight one was making short work of everything, nursing fingers after doing up harness with minus temperatures and nasty cold winds: by supper time the next morning we were sitting on our sledges writing up our diaries or meteorological logs, and even dabbling our bare toes in the snow, but not for long! Shades of darkness! How different all this was from what we had been through. My personal impression of this early summer sledging on the Barrier was one of constant wonder at its comfort. One had forgotten that a tent could be warm and a sleeping-bag dry: so deep were the contrary impressions that only actual experience was convincing. “It is a sweltering day, the air breathless, the glare intense—one loses sight of the fact that the temperature is low [−22°], one’s mind seeks comparison in hot sunlit streets and scorching pavements, yet six hours ago my thumb was frostbitten. All the inconveniences of frozen footwear and damp clothes and sleeping-bags have vanished entirely.”189

We could not expect to get through this windy area of Corner Camp without some bad weather. The windblown surface improved, the ponies took their heavier loads with ease, but as we came to our next camp it was banking up to the S. E. and the breeze freshened almost immediately. We built pony walls hurriedly and by the time we had finished supper it was blowing force 5 (a.m. November 6, Camp 4). There was a moderate gale with some drift all day which increased to force 8 with more drift at night. It was impossible to march. The drift took off a bit the next morning, and Meares and Dimitri with the two dog-teams appeared and camped astern of us. This was according to previous plan by which the dog-teams were to start after us and catch us up, since they travelled faster than the ponies. “The snow and drift necessitated digging out ponies again and again to keep them well sheltered from the wind. The walls made a splendid lee, but some sledges at the extremities were buried altogether, and our tent being rather close to windward of our wall got the back eddy and was continually being snowed up above the door. After noon the snow ceased except for surface drift. Snatcher knocked his section of the wall over, and Jehu did so more than ever. All ponies looked pretty miserable, as in spite of the shelter they were bunged up, eyes and all, in drift which had become ice and could not be removed without considerable difficulty.”190

Towards evening it ceased drifting altogether, but a wind, force 4, kept up with disconcerting regularity. Eventually Atkinson’s party got away at midnight. “Castle Rock is still visible, but will be closed by the north end of White Island in the next march—then goodbye to the old landmarks for many a long day.”191

The next day (November 8–9) “started at midnight and had a very pleasant march. Truly sledging in such weather is great. Mounts Discovery and Morning, which we gradually closed, looked fine in the general panorama of mountains. We are now nearly abreast the north end of the Bluff. We all came up to camp together this morning: it looked like a meet of the hounds, and Jehu ran away!!!”192

The next march was just the opposite. Wind force 5 to 6 and falling snow. “The surface was very slippery in parts and on the hard sastrugi it was a case of falling or stumbling continually. The light got so bad that one might have been walking in the clouds for all that could be discerned, and yet it was only snowing slightly. The Bluff became completely obscured, and the usual signs of a blizzard were accentuated.

“At lunch camp Scott packed up and followed us. We overhauled Atkinson about 1½ hours later, he having camped, and we were not sorry, as in addition to marching against a fresh southerly breeze the light brought a tremendous strain on the eyes in following tracks.”193 A little more than eight miles for the day’s total.

We carried these depressing conditions for three more marches, that is till the morning of November 13. The surface was wretched, the weather horrid, the snow persistent, covering everything with soft downy flakes, inch upon inch, and mile upon mile. There are glimpses of despondency in the diaries. “If this should come as an exception, our luck will be truly awful. The camp is very silent and cheerless, signs that things are going awry.”194 “The weather was horrid, overcast, gloomy, snowy. One’s spirits became very low.”195 “I expected these marches to be a little difficult, but not near so bad as today.”196 Indefinite conditions always tried Scott most: positive disasters put him into more cheerful spirits than most. In the big gale coming South when the ship nearly sank, and when we lost one of the cherished motors through the sea-ice, his was one of the few cheerful faces I saw. Even when the ship ran aground off Cape Evans he was not despondent. But this kind of thing irked him. Bowers wrote: “The unpleasant weather and bad surface, and Chinaman’s indisposition, combined to make the outlook unpleasant, and on arrival [in camp] I was not surprised to find that Scott had a grievance. He felt that in arranging the consumption of forage his own unit had not been favoured with the same reduction as ours, in fact accused me of putting upon his three horses to save my own. We went through the weights in detail after our meal, and, after a certain amount of argument, decided to carry on as we were going. I can quite understand his feelings, and after our experience of last year a bad day like this makes him fear our beasts are going to fail us. The Talent [i.e. the doctors] examined Chinaman, who begins to show signs of wear. Poor ancient little beggar, he ought to be a pensioner instead of finishing his days on a job of this sort. Jehu looks pretty rocky too, but seeing that we did not expect him to reach the Glacier Tongue, and that he has now done more than 100 miles from Cape Evans, one really does not know what to expect of these creatures. Certainly Titus thinks, as he has always said, that they are the most unsuitable scrapheap crowd of unfit creatures that could possibly be got together.”197

“The weather was about as poisonous as one could wish; a fresh breeze and driving snow from the E. with an awful surface. The recently fallen snow thickly covered the ground with powdery stuff that the unfortunate ponies fairly wallowed in. If it was only ourselves to consider I should not mind a bit, but to see our best ponies being hit like this at the start is most distressing. A single march like that of last night must shorten their usefulness by days, and here we are a fortnight out, and barely one-third of the distance to the glacier covered, with every pony showing signs of wear. Victor looks a lean and lanky beast compared with his condition two weeks ago.”198

But the ponies began to go better; and it was about this time that Jehu was styled the Barrier Wonder, and Chinaman the Thunderbolt. “Our four ponies have suffered most,” writes Bowers. “I don’t agree with Titus that it is best to march them right through without a lunch camp. They were undoubtedly pretty tired, and worst of all did not go their feeds properly. It was a fine warm morning for them (Nov. 13); +15°, our warmest temperature hitherto. In the afternoon it came on to snow in large flakes like one would get at home. I have never seen such snow down here before; it makes the surface very bad for the sledges. The ponies’ manes and rugs were covered in little knots of ice.”

The next march (November 13–14) was rather better, though the going was very deep and heavy, and all the ponies were showing signs of wear and tear. This was followed by a delightfully warm day, and all the animals were standing drowsily in the sunshine. We could see the land far away behind us, the first sight of land we had had for many days. On November 15 we reached One Ton Depot, having travelled a hundred and thirty miles from Hut Point.

The two sledges left standing were still upright, and the tattered remains of a flag flapped over the main cairn. In a salt tin lashed to the bamboo flagpole was a note from Lieutenant Evans to say that he had gone on with the motor party five days before, and would continue man-hauling to 80° 0′ S. and await us there. “He has done something over 30 miles in 2½ days—exceedingly good going.”199 We dug out the cairn, which we found just as we had left it except that there was a big tongue of drift, level with the top of the cairn to leeward, and running about 150 yards to N. E., showing that the prevailing wind here is S. W. Nine months before we had sprinkled some oats on the surface of the snow hoping to get a measurement of the accretion of snow during the winter. Unfortunately we were unable to find the oats again, but other evidence went to show that the snow deposit was very small. A minimum thermometer which was lashed with great care to a framework registered −73°. After the temperatures already experienced by us on the Barrier during the winter and spring this was surprisingly high, especially as our minimum temperatures were taken under the sledge, which means that the thermometer is shaded from radiation, while this thermometer at One Ton was left open to the sky. On the Winter Journey we found that a shaded thermometer registered −69° when an unshaded one registered −75°, a difference of 6°. All the provisions left here were found to be in excellent condition.

We then had a prolonged council of war. This meant that Scott called Bowers, and perhaps Oates, into our tent after supper was finished in the morning. Somehow these conferences were always rather seriocomic. On this occasion, as was usually the case, the question was ponies. It was decided to wait here one day and rest them, as there was ample food. The main discussion centred round the amount of forage to be taken on from here, while the state of the ponies, the amount they could pull and the distance they could go had to be taken into consideration.

“Oates thinks the ponies will get through, but that they have lost condition quicker than he expected. Considering his usually pessimistic attitude this must be thought a hopeful view. Personally I am much more hopeful. I think that a good many of the beasts are actually in better form than when they started, and that there is no need to be alarmed about the remainder, always excepting the weak ones which we have always regarded with doubt. Well, we must wait and see how things go.”200

The decision made was to take just enough food to get the ponies to the glacier, allowing for the killing of some of them before that date. It was obvious that Jehu and Chinaman could not go very much farther, and it was also necessary that ponies should be killed in order to feed the dogs. The two dog-teams were carrying about a week’s pony food, but they were unable to advance more than a fortnight from One Ton without killing ponies.

This decision practically meant that Scott abandoned the idea of taking ponies up the glacier. This was a great relief, for the crevassed state of the lower reaches of the glacier as described by Shackleton led us to believe that the attempt was suicidal. All the winter our brains were exercised to try and devise some method by which the ponies could be driven from behind, and by which the connection between pony and sledge could be loosed if the pony fell into a crevasse, but I confess that there seemed little chance of this happening. From all we saw of the glacier I am convinced that there is no reasonable chance of getting ponies up it, and that dogs could only be driven down it if the way up was most carefully surveyed and kept on the return. I am sure that in this kind of uncertainty the mental strain on the leader of a party is less than that on his men. The leader knows quite well what he thinks worth while risking or not: in this case Scott probably was always of the opinion that it would not be worth while taking ponies on to the glacier. The pony leaders, however, only knew that the possibility was ahead of them. I can remember now the relief with which we heard that it was not intended that Wilson should take Nobby, the fittest of our ponies, farther than the Gateway.

Up to now Christopher had lived up to his reputation, as the following extracts from Bowers’ diary will show:

“Three times we downed him, and he got up and threw us about, with all four of us hanging on like grim death. He nearly had me under him once; he seems fearfully strong, but it is a pity he wastes so much good energy. … Christopher, as usual, was strapped on three legs and then got down on his knees. He gets more cunning each time, and if he does not succeed in biting or kicking one of us before long it won’t be his fault. He finds the soft snow does not hurt his knees like the sea-ice, and so plunges about on them ad lib. One’s finnesko are so slippery that it is difficult to exert full strength on him, and today he bowled Oates over and got away altogether. Fortunately the lashing on his fourth leg held fast, and we were able to secure him when he rejoined the other animals. Finally he lay down, and thought he had defeated us, but we had the sledge connected up by that time, and as he got up we rushed him forward before he had time to kick over the traces. … Dimitri came and gave us a hand with Chris. Three of us hung on to him while the other two connected up the sledge. We had a struggle for over twenty minutes, and he managed to tread on me, but no damage done. … Got Chris in by a dodge. Titus did away with his back strap, and nearly had him away unaided before he realized that the hated sledge was fast to him. Unfortunately he started off just too soon, and bolted with only one trace fast. This pivoted him to starboard, and he charged the line. I expected a mixup, but he stopped at the wall between Bones and Snatcher, and we cast off and cleared sledge before trying again. By laying the traces down the side of the sledge instead of ahead we got him off his guard again, and he was away before he knew what had occurred. … We had a bad time with Chris again. He remembered having been bluffed before, and could not be got near the sledge at all. Three times he broke away, but fortunately he always ran back among the other ponies, and not out on to the Barrier. Finally we had to down him, and he was so tired with his recent struggles that after one abortive attempt we got him fast and away.”

Meanwhile it was not so much the difficulties of sledging as the depressing blank conditions in which our march was so often made, that gave us such troubles as we had. The routine of a tent makes a lot of difference. Scott’s tent was a comfortable one to live in, and I was always glad when I was told to join it, and sorry to leave. He was himself extraordinarily quick, and no time was ever lost by his party in camping or breaking camp. He was most careful, some said overcareful but I do not think so, that everything should be neat and shipshape, and there was a recognized place for everything. On the Depot Journey we were bidden to see that every particle of snow was beaten off our clothing and finnesko before entering the tent: if it was drifting we had to do this after entering and the snow was carefully cleared off the floor-cloth. Afterwards each tent was supplied with a small brush with which to perform this office. In addition to other obvious advantages this materially helped to keep clothing, finnesko, and sleeping-bags dry, and thus prolong the life of furs. “After all is said and done,” said Wilson one day after supper, “the best sledger is the man who sees what has to be done, and does it—and says nothing about it.” Scott agreed. And if you were “sledging with the Owner” you had to keep your eyes wide open for the little things which cropped up, and do them quickly, and say nothing about them. There is nothing so irritating as the man who is always coming in and informing all and sundry that he has repaired his sledge, or built a wall, or filled the cooker, or mended his socks.

I moved into Scott’s tent for the first time in the middle of the Depot Journey, and was enormously impressed by the comfort which a careful routine of this nature evoked. There was a homelike air about the tent at supper time, and, though a lunch camp in the middle of the night is always rather bleak, there was never anything slovenly. Another thing which struck me even more forcibly was the cooking. We were of course on just the same ration as the tent from which I had come. I was hungry and said so. “Bad cooking,” said Wilson shortly; and so it was. For in two or three days the sharpest edge was off my hunger. Wilson and Scott had learned many a cooking tip in the past, and, instead of the same old meal day by day, the weekly ration was so manoeuvred by a clever cook that it was seldom quite the same meal. Sometimes pemmican plain, or thicker pemmican with some arrowroot mixed with it: at others we surrendered a biscuit and a half apiece and had a dry hoosh, i.e. biscuit fried in pemmican with a little water added, and a good big cup of cocoa to follow. Dry hooshes also saved oil. There were cocoa and tea upon which to ring the changes, or better still “teaco” which combined the stimulating qualities of tea with the food value of cocoa. Then much could be done with the dessertspoonful of raisins which was our daily whack. They were good soaked in the tea, but best perhaps in with the biscuits and pemmican as a dry hoosh. “You are going far to earn my undying gratitude, Cherry,” was a satisfied remark of Scott one evening when, having saved, unbeknownst to my companions, some of their daily ration of cocoa, arrowroot, sugar and raisins, I made a “chocolate hoosh.” But I am afraid he had indigestion next morning. There were meals when we had interesting little talks, as when I find in my diary that: “we had a jolly lunch meal, discussing authors. Barrie, Galsworthy and others are personal friends of Scott. Someone told Max Beerbohm that he was like Captain Scott, and immediately, so Scott assured us, he grew a beard.”

But about three weeks out the topics of conversation became threadbare. From then onwards it was often that whole days passed without conversation beyond the routine Camp ho! All ready? Pack up. Spell ho. The latter after some two hours’ pulling. When man-hauling we used to start pulling immediately we had the tent down, the sledge packed and our harness over our bodies and ski on our feet. After about a quarter of an hour the effects of the marching would be felt in the warming of hands and feet and the consequent thawing of our mitts and finnesko. We then halted long enough for everybody to adjust their ski and clothing: then on, perhaps for two hours or more, before we halted again.

Since it had been decided to lighten the ponies’ weights, we left at least 100 lbs. of pony forage behind when we started from One Ton on the night of November 16–17 on our first 13-mile march. This was a distinct saving, and instead of 695 lbs. each with which the six stronger ponies left Corner Camp, they now pulled only 625 lbs. Jehu had only 455 lbs. and Chinaman 448 lbs. The dog-teams had 860 lbs. of pony food between them, and according to plan the two teams were to carry 1,570 lbs. from One Ton between them. These weights included the sledges, with straps and fittings, which weighed about 45 lbs.

Summer seemed long in coming for we marched into a considerable breeze and the temperature was −18°. Oates and Seaman Evans had quite a crop of frostbites. I pointed out to Meares that his nose was gone; but he left it, saying that he had got tired of it, and it would thaw out by and by. The ponies were going better for their rest. The next day’s march was over crusty snow with a layer of loose powdery snow at the top, and a temperature of −21° was chilly. Towards the end of it Scott got frightened that the ponies were not going as well as they should. Another council of war was held, and it was decided that an average of thirteen miles a day must be done at all costs, and that another sack of forage should be dumped here, putting the ponies on short rations later, if necessary. Oates agreed, but said the ponies were going better than he expected: that Jehu and Chinaman might go a week, and almost certainly would go three days. Bowers was always against this dumping. Meanwhile Scott wrote: “It’s touch and go whether we scrape up to the glacier; meanwhile we get along somehow.”201

As a result of one of Christopher’s tantrums Bowers records that his sledge-meter was carried away this morning: “I took my sledge-meter into the tent after breakfast and rigged up a fancy lashing with raw hide thongs so as to give it the necessary play with security. A splendid parhelia exhibition was caused by the ice-crystals. Round the sun was a 22° halo [that is a halo 22° from the sun’s image], with four mock suns in rainbow colours, and outside this another halo in complete rainbow colours. Above the sun were the arcs of two other circles touching these halos, and the arcs of the great all-round circle could be seen faintly on either side. Below was a dome-shaped glare of white which contained an exaggerated mock sun, which was as dazzling as the sun himself. Altogether a fine example of a pretty common phenomenon down here.” And the next day: “We saw the party ahead in inverted mirage some distance above their heads.”

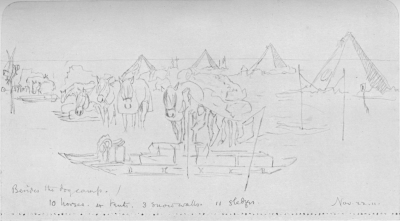

In the next three marches we covered our daily 13 miles, for the most part without very great difficulty. But poor Jehu was in a bad way, stopping every few hundred yards. It was a funereal business for the leaders of these crock ponies; and at this stage of the journey Atkinson, Wright and Keohane had many more difficulties than most of us, and the success of their ponies was largely due to their patience and care. Incidentally big icicles formed upon the ponies’ noses during the march and Chinaman used Wright’s windproof blouse as a handkerchief. During the last of these marches, that is on the morning of November 21, we saw a massive cairn ahead, and found there the motor party, consisting of Lieutenant Evans, Day, Lashly and Hooper. The cairn was in 80° 2′, and under the name Mount Hooper formed our Upper Barrier Depot. We left there three S (summit) rations, two cases of emergency biscuits and two cases of oil, which constituted three weekly food units for the three parties which were to advance from the bottom of the Beardmore Glacier. This food was to take them back from 80° 2′ to One Ton Camp. We all camped for the night 3 miles farther on: sixteen men, five tents, ten ponies, twenty-three dogs and thirteen sledges.

The man-hauling party had been waiting for six days; and, having expected us before, were getting anxious about us. They declared that they were very hungry, and Day, who was always long and thin, looked quite gaunt. Some spare biscuits which we gave them from our tent were carried off with gratitude. The rest of us who were driving dogs or leading ponies still found our Barrier ration satisfying.

We had now been out three weeks and had travelled 192 miles, and formed a very good idea as to what the ponies could do. The crocks had done wonderfully:—“We hope Jehu will last three days; he will then be finished in any case and fed to the dogs. It is amusing to see Meares looking eagerly for the chance of a feed for his animals; he has been expecting it daily. On the other hand, Atkinson and Oates are eager to get the poor animal beyond the point at which Shackleton killed his first beast. Reports on Chinaman are very favourable, and it really looks as though the ponies are going to do what is hoped of them.”202 From first to last Nobby, who was rescued from the floe, was the strongest pony we had, and was now drawing a heavier load than any other pony by 50 lbs. He was a well-shaped, contented kind of animal, misnamed a pony. Indeed several of our beasts were too large to fit this description. Christopher, of course, was wearing himself out quicker than most, but all of them had lost a lot of weight in spite of the fact that they had all the oats and oil-cake they could eat. Bowers writes of his pony:

“Victor, my pony, has taken to leading the line, like his opposite number last season. He is a steady goer, and as gentle as a dear old sheep. I can hardly realize the strenuous times I had with him only a month ago, when it took about four of us to get him harnessed to a sledge, and two of us every time with all our strength to keep him from bolting when in it. Even at the start of the journey he was as nearly unmanageable as any beast could be, and always liable to bolt from sheer excess of spirits. He is more sober now after three weeks of featureless Barrier, but I think I am more fond of him than ever. He has lost his rotundity, like all the other horses, and is a long-legged, angular beast, very ugly as horses go, but still I would not change him for any other.”

The ponies were fed by their leaders at the lunch and supper halts, and by Oates and Bowers during the sleep halt about four hours before we marched. Several of them developed a troublesome habit of swinging their nosebags off, some as soon as they were put on, others in their anxiety to reach the corn still left uneaten in the bottom of the bag. We had to lash their bags on to their headstalls. “Victor got hold of his head rope yesterday, and devoured it: not because he is hungry, as he won’t eat all his allowance even now.”203

The original intention was that Day and Hooper should return from 80° 0′, but it was now decided that their unit of four should remain intact for a few days, and constitute a light man-hauling advance party to make the track.

The weather was much more pleasant and we saw the sun most days, while I note only one temperature below −20° since leaving One Ton. The ponies sank in a cruel distance some days, but we were certainly not overworking them and they had as much food as they could eat. We knew the grim part was to come, but we never realized how grim it was to be. From this Northern Barrier Depot the ponies were mostly drawing less than 500 lbs. and we had hopes of getting through to the glacier without much difficulty. All depended on the weather, and just now it was glorious, and the ponies were going steadily together. Jehu, the crockiest of the crocks, was led back along the track and shot on the evening of November 24, having reached a point at least 15 miles beyond that where Shackleton shot his first pony. When it is considered that it was doubtful whether he could start at all this must be conceded to have been a triumph of horse-management in which both Oates and Atkinson shared, though neither so much as Jehu himself, for he must have had a good spirit to have dragged his poor body so far. “A year’s care and good feeding, three weeks’ work with good treatment, a reasonable load and a good ration, and then a painless end. If anybody can call that cruel I cannot either understand it or agree with them.” Thus Bowers, who continues: “The midnight sun reflected from the snow has started to burn my face and lips. I smear them with hazeline before turning in, and find it a good thing. Wearing goggles has absolutely prevented any recurrence of snow-blindness. Captain Scott says they make me see everything through rose-coloured spectacles.”

We said goodbye to Day and Hooper next morning, and they set their faces northwards and homewards.204 Two-men parties on the Barrier are not much fun. Day had certainly done his best about the motors and they had helped us over a bad bit of initial surface. That night Scott wrote: “Only a few more marches to feel safe in getting to our goal.”205 At the lunch halt on November 26, in lat. 81° 5′, we left our Middle Barrier Depot, containing one week’s provisions for each returning unit as at Mount Hooper, a reduction of 200 lbs. in our weights. The march that day was very trying. “It is always rather dismal work walking over the great snow plain when sky and surface merge in one pall of dead whiteness, but it is cheering to be in such good company with everything going on steadily and well.”206

There was no doubt that the animals were tiring, and “a tired animal makes a tired man, I find.”207 The next day (November 28) was no better: “the most dismal start imaginable. Thick as a hedge, snow falling and drifting with keen southerly wind.”208

Bowers notes: “We have now run down a whole degree of latitude without a fine day, or anything but clouds, mist, and driving snow from the south.” We certainly did have some difficult marches, one of the worst effects of which was that we knew we must be making a winding course and we had to pick up our depots on the return somehow. Here is a typical bad morning from Bowers’ diary:

“The first four miles of the march were utter misery for me, as Victor, either through lassitude or because he did not like having to plug into the wind, went as slow as a funeral horse. The light was so bad that wearing goggles was most necessary, and the driving snow filled them up as fast as you cleared them. I dropped a long way astern of the cavalcade, could hardly see them at times through the snow, but the fear that Victor, of all the beasts, should give out was like a nightmare. I have always been used to starting later than the others by a quarter of a mile, and catching them up. At the four-mile cairn I was about fed up to the neck with it, but I said very little as everybody was so disgusted with the weather and things in general that I saw that I was not the only one in tribulation. Victor turned up trumps after that. He stepped out and led the line in his old place, and at a good swinging pace considering the surface, my temper and spirits improving at every step. In the afternoon he went splendidly again, and finished up by rolling in the snow when I had taken his harness off, a thing he has not done for ten or twelve days. It certainly does not look like exhaustion!”

Indeed these days we were fighting for our marches, and Chinaman who was killed this night seemed well out of it. He reached a point less than 90 miles from the glacier, though this was small comfort to him.

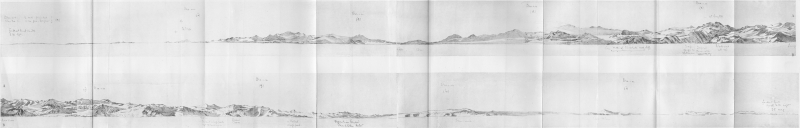

Stumbling and groping our way along as we had been during the last blizzard we were totally unprepared for the sight which met us during our next march on November 29. The great ramp of mountains which ran to the west of us, and would soon bar our way to the South, partly cleared: and right on top of us it seemed were the triple peaks of Mount Markham. After some 300 miles of bleak, monotonous Barrier it was a wonderful sight indeed. We camped at night in latitude 82° 1′ S., four miles beyond Scott’s previous Farthest South in 1902. Then they had the best of luck in clear fine weather, which Shackleton has also recorded at this stage of his southern journey.

It is curious to see how depressed all our diaries become when this bad weather obtained, and how quickly we must have cheered up whenever the sun came out. There is no doubt that a similar effect was produced upon the ponies. Truth to tell, the mental strain upon those responsible was very great in these early days, and there is little of outside interest to relieve the mind. The crystal surface which was an invisible carpet yesterday becomes a shining glorious sheet of many colours today: the irregularities which caused you so many falls are now quite clear and you step on or over them without a thought: and when there is added some of the most wonderful scenery in the world it is hard to recall in the enjoyment of the present how irritable and weary you felt only twenty hours ago. The whisper of the sledge, the hiss of the primus, the smell of the hoosh and the soft folds of your sleeping-bag: how jolly they can all be, and generally were.

I would that I could once again

Around the cooker sit

And hearken to its soft refrain

And feel so jolly fit.Instead of home-life’s silken chains,

The uneventful round,

I long to be mid snow-swept plains,

In harness, outward bound.With the pad, pad, pad, of fin’skoed feet,

(Nelson in The South Polar Times.)

With two hundred pounds per man,

Not enough hoosh or biscuit to eat,

Well done, lads! Up tent! Outspan.

Certainly as we skirted these mountains, range upon range, during the next two marches (November 30 and December 1), we felt we could have little cause for complaint. They brought us to lat. 82° 7′ S., and here we left our last depot on the Barrier, called the Southern Barrier Depot, with a week’s ration for each returning party as usual. “The man food is enough for one week for each returning unit of four men, the next depot beyond being the Middle Barrier Depot, 73 miles north. As we ought easily to do over 100 miles a week on the return journey, there is little likelihood of our having to go on short commons if all goes well.”209 And this was what we all felt—until we found the Polar Party. This was our twenty-seventh camp, and we had been out a month.

It was important that we should have fine clear weather during the next few days when we should be approaching the land. On his previous southern journey Scott had been prevented from reaching the range of mountains which ran along to our right by a huge chasm. This phenomenon is known to geologists as a shear crack and is formed by the movement of a glacier away from the land which bounds it. In this case a mass of many hundred miles of Barrier has moved away from the mountains, and the disturbance is correspondingly great. Shackleton has described how he approached the Gateway, as he named the passage between Mount Hope and the mainland, by means of which he passed through on to the Beardmore Glacier. As he and his companions were exploring the way they came upon an enormous chasm, 80 feet wide and 300 feet deep, which barred their path. Moving along to the right they found a place where the chasm was filled with snow, and here they crossed to the land some miles ahead. At our Southern Barrier Depot we reckoned we were some forty-four miles from this Gateway and in three more marches we hoped to be camped under this land.

Christopher was shot at the depot. He was the only pony who did not die instantaneously. Perhaps Oates was not so calm as usual, for Chris was his own horse though such a brute. Just as Oates fired he moved, and charged into the camp with the bullet in his head. He was caught with difficulty, nearly giving Keohane a bad bite, led back and finished. We were well rid of him: while he was strong he fought, and once the Barrier had tamed him, as we were not able to do, he never pulled a fair load. He could have gone several more days, but there was not enough pony food to take all the animals forward. We began to wonder if we had done right to leave so much behind. Each pony provided at least four days’ food for the dog-teams, some of them more, and there was quite a lot of fat on them—even on Jehu. This was comforting, as going to prove that their hardships were not too great. Also we put the undercut into our own hoosh, and it was very good, though we had little oil to cook it.

We had been starting later each night, in order that the transition from night to day marching might be gradual. For we intended to march by day when we started pulling up the glacier, and there were no ponies to rest when the sun was high. It may be said therefore that our next march was on December 2.

Before we started Scott walked over to Bowers. “I have come to a decision which will shock you.” Victor was to go at the end of the march, because pony food was running so short. Birdie wrote at the end of the day:—He “did a splendid march and kept ahead all day, and as usual marched into camp first, pulling over 450 lbs. easily. It seemed an awful pity to have to shoot a great strong animal, and it seemed like the irony of fate to me, as I had been downed for over-provisioning the ponies with needless excess of food, and the drastic reductions had been made against my strenuous opposition up to the last. It is poor satisfaction to me to know that I was right now that my horse is dead. Good old Victor! He has always had a biscuit out of my ration, and he ate his last before the bullet sent him to his rest. Here ends my second horse in 83° S., not quite so tragically as my first when the sea-ice broke up, but none the less I feel sorry for a beast that has been my constant companion and care for so long. He has done his share in our undertaking anyhow, and may I do my share as well when I get into harness myself.

“The snow has started to fall over his bleak resting-place, and it looks like a blizzard. The outlook is dark, stormy and threatening.”

Indeed it had been a dismal march into a blank white wall, and the ponies were sinking badly in the snow, leaving holes a full foot deep. The temperature was +17° and the flakes of snow melted when they lay on the dark colours of the tents and our furs. After building the pony walls water was running down our windproofs.

I note “we are doing well on pony meat and go to bed very content.” Notwithstanding the fact that we could not do more than heat the meat by throwing it into the pemmican we found it sweet and good, though tough. The man-hauling party consisted of Lieut. Evans and Lashly who had lost their motors, and Atkinson and Wright who had lost their ponies. They were really quite hungry by now, and most of us pretty well looked forward to our meals and kept a biscuit to eat in our bags if we could. The pony meat therefore came as a relief. I think we ought to have depoted more of it on the cairns. As it was, what we did not eat was given to the dogs. With some tins of extra oil and a depoted pony the Polar Party would probably have got home in safety.

On December 3 we roused out at 2:30 a.m. It was thick and snowy. As we breakfasted the blizzard started from the southeast, and was soon blowing force 9, a full gale, with heavy drift. “The strongest wind I have known here in summer.”210 It was impossible to start, but we turned out and made up the pony walls in heavy drift, one of them being blown down three times. By 1:30 p.m. the sun was shining, and the land was clear. We started at 2, with what we thought was Mount Hope showing up ahead, but soon great snow-clouds were banking up and in two hours we were walking in a deep gloom which made it difficult to find the track made by the man-hauling party ahead. By the time we reached the cairn, which was always built at the end of the first four miles, it was blowing hard from the N. N. W. of all the unlikely quarters of the compass. Bowers and Scott were on ski.

“I put on my windproof blouse and nosed out the track for two miles, when we suddenly came upon the tent of the leading party. They had camped owing to the difficulty of steering a course in such thick weather. The ponies, however, with the wind abaft the beam were going along splendidly, and Scott thought it worth while to shove on. We therefore carried on another four miles, making ten in all, a good half march, before we camped. On ski it was simply ripping, except for the inability to see anything at all. With the wind behind, and the good sliding surface made by the wind-hardened snow, one fairly slithered along. Camping was less pleasant as it was blowing a gale by that time. We are all in our bags again now, with a good hot meal inside one, and blow high or blow low one might be in a worse place than a reindeer bag.”211

It was all right for the people on ski (and this in itself gave us a certain sense of grievance), but things had not been so easy with the ponies, who were sinking very deeply in places, while we ourselves were sinking well over our ankles. This day we began to cross the great undulations in the Barrier, with the crests some mile apart, which here mark the approach to the land. We had built the walls to the north of the ponies on camping, because the wind was from that direction, but by breakfast on December 4 it was blowing a thick blizzard from the southeast. We began to feel bewildered by these extraordinary weather changes, and not a little exasperated too. Again we could not march, and again we had to dig out the sledges and ponies, and to move them all round to the other side of the walls which we had partly to rebuild. “Oh for the simple man-hauling life!” was our thought, and “poor helpless beasts—this is no country for live stock.” By this time we could not see the neighbouring tents for the drift. The situation was not improved by the fact that our tent doors, the tents having been pitched for the strong north wind then blowing, were now facing the blizzard, and sheets of snow entered with each individual. The man-hauling party came up just before the worst of the blizzard started. The dogs alone were comfortable, buried deep beneath the drifted snow. The sailors began to debate who was the Jonah. They said he was the cameras. The great blizzard was brewing all about us.

But at midday as though a curtain was rolled back, the thick snow fog cleared off, while at the same time the wind fell calm, and a great mountain appeared almost on the top of us. Far away to the southeast we could distinguish, by looking very carefully, a break in the level Barrier horizon—a new mountain which we reckoned must be at least in latitude 86° and very high. Towards it the ranges stretched away, peak upon peak, range upon range, as far as the eye could see. “The mountains surpassed anything I have ever seen: beside the least of these giants Ben Nevis would be a mere mound, and yet they are so immense as to dwarf each other. They are intersected at every turn with mighty glaciers and icefalls and eternally ice-filled valleys that defy description. So clear was everything that every rock seemed to stand out, and the effect of the sun as he came round (between us and the mountains) was to make the scene still more beautiful.”212

Altogether we marched eleven miles this day, and camped right in front of the Gateway, which we reckoned to be some thirteen miles away. We saw no crevasses but crossed ten or twelve very large undulations, and estimated that the dips between them were twelve to fifteen feet. Mount Hope was bigger than we expected, and beyond it, stretching out into the Barrier as far as we could see, was a great white line of jagged edges, the chaos of pressure which this vast glacier makes as it flows into the comparatively stationary ice of the Barrier.

My own pony Michael was shot after we came into camp. He was as attractive a little beast as we had. His light weight helped him on soft surfaces, but his small hoofs let him in farther than most and I notice in Scott’s diary that on November 19 the ponies were sinking halfway to the hock, and Michael once or twice almost to the hock itself. A highly strung, spirited animal, his off days took the form of fidgets, during which he would be constantly trying to stop and eat snow, and then rush forward to catch up the other ponies. Life was a constant source of wonder to him, and no movement in the camp escaped his notice. Before we had been long on the Barrier he developed mischievous habits and became a rope eater and gnawer of other ponies’ fringes, as we called the coloured tassels we hung over their eyes to ward off snow-blindness. However, he was by no means the only culprit, and he lost his own fringe to Nobby quite early in the proceedings. It was not that he was hungry, for he never quite finished his own feed. At any rate he enjoyed the few weeks before he died, pricking up his ears and getting quite excited when anything happened, and the arrival of the dog-teams each morning after he had been tethered sent him to bed with much to dream of. And I must say his master dreamed pretty regularly too. Michael was killed right in front of the Gateway on December 4, just before the big blizzard, which, though we did not know it, was on the point of breaking upon us, and he was untying his cloth and chewing up everything he could reach to the last. “It was decided after we camped, and he had his feed already on: Meares reported that he had no more food for the dogs. He walked away, and rolled in the snow on the way down, not having done so when we got in. He was just like a naughty child all the way, and pulled all out. He has been a good friend, and has a good record, 82° 3′ S. He was a bit done today: the blizzard had knocked him. Gallant little Michael!”213

As we got into our bags the mountain tops were fuzzy with drift. We wanted one clear day to get across the chasm: one short march and the ponies’ task was done. Their food was nearly finished. Scott wrote that night: “We are practically through with the first stage of our journey.”214

“Tuesday, December 5. Camp 30. Noon. We awoke this morning to a raging howling blizzard. The blows we have had hitherto have lacked the very fine powdering snow, that especial feature of the blizzard. Today we have it fully developed. After a minute or two in the open one is covered from head to foot. The temperature is high, so that what falls or drives against one sticks. The ponies—heads, tails, legs and all parts not protected by their rugs—are covered with ice; the animals are standing deep in snow, the sledges are almost covered, and huge drifts above the tents. We have had breakfast, rebuilt the walls, and are now again in our bags. One cannot see the next tent, let alone the land. What on earth does such weather mean at this time of year? It is more than our share of ill-fortune, I think, but the luck may turn yet. …

“11 p.m. It has blown hard all day with quite the greatest snowfall I remember. The drifts about the tents are simply huge. The temperature was −27° this forenoon, and rose to +31° in the afternoon, at which time the snow melted as it fell on anything but the snow, and, as a consequence, there are pools of water on everything, the tents are wet through, also the wind-clothes, night-boots, etc.; water drips from the tent poles and door, lies on the floor-cloth, soaks the sleeping-bags, and makes everything pretty wretched. If a cold snap follows before we have had time to dry our things, we shall be mighty uncomfortable. Yet after all it would be humorous enough if it were not for the seriousness of delay—we can’t afford that, and it’s real hard luck that it should come at such a time. The wind shows signs of easing down, but the temperature does not fall and the snow is as wet as ever, not promising signs of abatement.

“Wednesday, December 6. Camp 30. Noon. Miserable, utterly miserable. We have camped in the ‘Slough of Despond.’ The tempest rages with unabated violence. The temperature has gone to +33°; everything in the tent is soaking. People returning from the outside look exactly as though they had been in a heavy shower of rain. They drip pools on the floor-cloth. The snow is steadily climbing higher about walls, ponies, tents and sledges. The ponies look utterly desolate. Oh! But this is too crushing, and we are only 12 miles from the glacier. A hopeless feeling descends on one and is hard to fight off. What immense patience is needed for such occasions!”215

Bowers describes the situation as follows:

“It is blowing a blizzard such as one might expect to be driven at us by all the powers of darkness. It may be interesting to describe it, as it is my first experience of a really warm blizzard, and I hope to be troubled by cold ones only, or at least moderate ones only, in future as regards temperature.

“When I swung the thermometer this morning I looked and looked again, but unmistakably the temperature was +33° F, above freezing point (out of the sun’s direct rays) for the first time since we came down here. What this means to us nobody can conceive. We try to treat it as a huge joke, but our wretched condition might be amusing to read of it later. We are wet through, our tents are wet, our bags which are our life to us and the objects of our greatest care, are wet; the poor ponies are soaked and shivering far more than they would be ordinarily in a temperature fifty degrees lower. Our sledges—the parts that are dug out—are wet, our food is wet, everything on and around and about us is the same—wet as ourselves and our cold, clammy clothes. Water trickles down the tent poles and only forms icicles in contact with the snow floor. The warmth of our bodies has formed a snow bath in the floor for each of us to lie in. This is a nice little catchwater for stray streams to run into before they freeze. This they cannot do while a warm human lies there, so they remain liquid and the accommodating bag mops them up. When we go out to do the duties of life, fill the cooker, etc., for the next meal, dig out or feed the ponies, or anything else, we are bunged up with snow. Not the driving, sandlike snow we are used to, but great slushy flakes that run down in water immediately and stream off you. The drifts are tremendous, the rest of the show is indescribable. I feel most for the unfortunate animals and am thankful that poor old Victor is spared this. I mended a pair of half mitts today, and we are having two meals instead of three. This idleness when one is simply jumping to go on is bad enough for most, but must be worse for Captain Scott. I feel glad that he has Dr. Bill (Wilson) in his tent; there is something always so reassuring about Bill, he comes out best in adversity.”216

“Thursday, December 7. Camp 30. The storm continues and the situation is now serious. One small feed remains for the ponies after today, so that we must either march tomorrow or sacrifice the animals. That is not the worst; with the help of the dogs we could get on, without doubt. The serious part is that we have this morning started our Summit rations—that is to say, the food calculated from the Glacier Depot has been begun. The first supporting party can only go on a fortnight from this date and so forth.”217

This day was just as warm, and wetter—much wetter. The temperature was +35.5°, and our bags were like sponges. The huge drifts had covered everything, including most of the tent, the pony walls and sledges. At intervals we dug our way out and dug up the wretched ponies, and got them on to the top again.

“Henceforward our full ration will be 16 oz. biscuit, 12 oz. pemmican, 2 oz. butter, 0.57 oz. cocoa, 3.0 oz. sugar and 0.86 oz. tea. This is the Summit ration, total 34.43 oz., with a little onion powder and salt. I am all for this: Seaman Evans and others are much regretting the loss of chocolate, raisins and cereals. For the first week up the glacier we are to go one biscuit short to provision Meares on the way back. The motors depoted too much and Meares has been brought on far farther than his orders were originally bringing him. Originally he was to be back at Hut Point on December 10. The dogs, however, are getting all the horse that is good for them, and are very fit. He has to average 24 miles a day going back. Michael is well out of this: we are now eating him. He was in excellent condition and tastes very good, though tough.”218

By this time there was little sleep left for us as we lay in our sleeping-bags. Three days generally see these blizzards out, and we hoped much from Friday, December 8. But when we breakfasted at 10 a.m. (we were getting into day-marching routine) wind and snow were monotonously the same. The temperature rose to +34.3°. These temperatures and those recorded by Meares on his way home must be a record for the interior of the Barrier. So far as we were concerned it did not much matter now whether it was +40° or +34°. Things did look really gloomy that morning.

But at noon there came a gleam of comfort. The wind dropped, and immediately we were out plunging about, always up to our knees in soft downy snow, and often much farther. First we shifted our tents, digging them up with the greatest care that the shovel might not tear them. The valances were encased in solid ice from the water which had run down. Then we started to find our sledges which were about four feet down: they were dragged out, and everything on them was wringing wet. There was a gleam of sunshine, which soon gave place to snow and gloom, but we started to make experiments in haulage. Four men on ski managed to move a sledge with four others sitting upon it. Nobby was led out, but sank to his belly. As for the drifts I saw Oates standing behind one, and only his head appeared, and this was all loose snow.

“We are all sitting round now after some tea—it is much better than getting into the bags. I can hardly think that the ponies can pull on, but Titus thinks they can pull tomorrow; all the food is finished, and what they have had today was only what they would not eat out of their last feed yesterday. It is a terrible end—driven to death on no more food, to be then cut up, poor devils. I have swapped the Little Minister with Silas Wright for Dante’s Inferno!”219 The steady patter of the falling snow upon the tents was depressing as we turned in, but the temperature was below freezing.

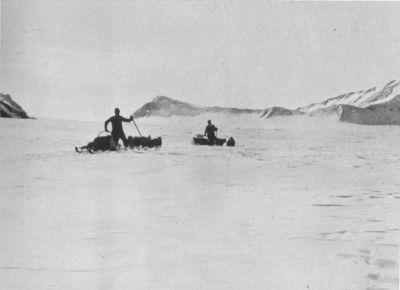

The next morning (Saturday, December 9) we turned out to a cloudy snowy day at 5:30 a.m. By 8:30 we had hauled the sledges some way out of the camp and started to lead out the ponies. “The horses could hardly move, sank up to their bellies, and finally lay down. They had to be driven, lashed on. It was a grim business.”220

My impressions of that day are of groping our way, for Bowers and I were pulling a light sledge ahead to make the track, through a vague white wall. First a confused crowd of men behind us gathered round the leading pony sledge, pushing it forward, the poor beast barely able to struggle out of the holes it made as it plunged forward. The others were induced to follow, and after a start had been made the regular man-hauling party went back to fetch their load. There was not one man there who would willingly have caused pain to a living thing. But what else was to be done—we could not leave our pony depot in that bog. Hour after hour we plugged on: and we dare not halt for lunch, we knew we could never start again. After crossing many waves huge pressure ridges suddenly showed themselves all round, and we got on to a steep rise with the coastal chasm on our right hand appearing as a great dip full of enormous pressure. Scott was naturally worried about crevasses, and though we knew there was a way through, the finding of it in the gloom was most difficult. For two hours we zigzagged about, getting forward it is true, but much bewildered, and once at any rate almost bogged. Scott joined us, and we took off our ski so as to find the crevasses, and if possible a hard way through. Every step we sank about fifteen inches, and often above our knees. Meanwhile Snatcher was saving the situation in snowshoes, and led the line of ponies. Snippets nearly fell back into a big crevasse, into which his hind quarters fell: but they managed to unharness him, and scramble him out.

I do not know how long we had been going when Scott decided to follow the chasm. We found a big dip with hard ice underneath, and it was probably here that we made the crossing: we could now see the ring of pressure behind us. Almost it was decided to make the depot here, but the ponies still plugged on in the most plucky way, though they had to be driven. Scott settled to go as far as they could be induced to march, and they did wonderfully. We had never thought that they would go a mile: but painfully they marched for eleven hours without a long halt, and covered a distance which we then estimated at seven miles. But our sledge-meters were useless being clogged with the soft snow, and we afterwards came to believe the distance was not so great: probably not more than five. When we had reached a point some two miles from the top of the snow divide which fills the Gateway we camped, thankful to rest, but more thankful still that we need drive those weary ponies no more. Their rest was near. It was a horrid business, and the place was known as Shambles Camp.

Oates came up to Scott as he stood in the shadow of Mount Hope. “Well! I congratulate you, Titus,” said Wilson. “And I thank you, Titus,” said Scott.

And that was the end of the Barrier Stage.