VI

The First Winter

The highest object that human beings can set before themselves is not the pursuit of any such chimera as the annihilation of the unknown; it is simply the unwearied endeavour to remove its boundaries a little further from our little sphere of action.

Huxley

And so we came back to our comfortable hut. Whatever merit there may be in going to the Antarctic, once there you must not credit yourself for being there. To spend a year in the hut at Cape Evans because you explore is no more laudable than to spend a month at Davos because you have consumption, or to spend an English winter at the Berkeley Hotel. It is just the most comfortable thing and the easiest thing to do under the circumstances.

In our case the best thing was not at all bad, for the hut, as Arctic huts go, was as palatial as is the Ritz, as hotels go. Whatever the conditions of darkness, cold and wind, might be outside, there was comfort and warmth and good cheer within.

And there was a mass of work to be done, as well as at least two journeys of the first magnitude ahead.

When Scott first sat down at his little table at Winter Quarters to start working out a most complicated scheme of weights and averages for the Southern Journey, his thoughts were gloomy, I know. “This is the end of the Pole,” he said to me, when he pulled us off the bergs after the sea-ice had broken up; the loss of six ponies out of the eight with which we started the Depot Journey, the increasing emaciation and weakness of the pony transport as we travelled farther on the Barrier, the arrival of the dogs after their rapid journey home, starved rakes which looked as though they were absolutely done—these were not cheerful recollections with which to start to plan a journey of eighteen hundred miles.

On the other hand, we had ten ponies left, though two or three of them were of more than doubtful quality; and it was obvious that considerable improvement could and must be made in the feeding of both ponies and dogs. With regard to the dogs the remedy was plain; their ration was too small. With regard to the ponies the question was not so simple. One of the main foods for the ponies which we had brought was compressed fodder in the shape of bales. Theoretically this fodder was excellent food value, and was made of wheat which was cut green and pressed. Whether it was really wheat or not I do not know, but there could be no two opinions about its nourishing qualities for our ponies. When fed upon it they lost weight until they were just skin and bone. Poor beasts! It was pitiful to see them.

In Oates we had a man who had forgotten as much as most men know about horses. It was no fault of his that this fodder was inadequate, nor that we had lost so many of the best ponies which we had. Oates had always been for taking the worst ponies out on the Depot Journey: travelling as far on to the Barrier as they could go, and there killing them and depoting their flesh. Now Oates took the ten remaining ponies into his capable hands. Some of them were scarecrows, especially poor Jehu, who was never expected to start at all, and ended by gallantly pulling his somewhat diminished load eight marches beyond One Ton Camp, a distance of 238 miles. Another, Christopher, was a man-killer if ever a horse was; he had to be thrown in order to attach him to the sledge; to the end he would lay out any man who was rash enough to give him the chance; once started, and it took four men to achieve this, it was impossible to halt him during the day’s march, and so Oates and his three tent mates and their ponies had to go without any lunch meal for 130 miles of the Southern Journey.

Oates trained them and fed them as though they were to run in the Derby. They were exercised whenever possible throughout the winter and spring by those who were to lead them on the actual journey. Fresh and good food was found in the shape of oil-cake and oats, a limited quantity of each of which had been brought and was saved for the actual Polar Journey, and everything which care and foresight could devise was done to save them discomfort. It is a grim life for animals, but in the end we were to know that up to the time of that bad blizzard almost at the Glacier Gateway, which was the finishing post of these plucky animals, they had fed all they needed, slept as well and lived as well as any, and better than most horses in ordinary life at home. “I congratulate you, Titus,” said Wilson, as we stood under the shadow of Mount Hope, with the ponies’ task accomplished, and “I thank you,” said Scott.

Titus grunted and was pleased.

Transport difficulties for the Polar Journey were considerable, but in every other direction the outlook was bright. The men who were to do the sledging had been away from Winter Quarters for three months. They had had plenty of sledging experience, some of it none too soft. The sledges, clothing, man-food, and outfit generally were excellent, although some changes were suggested and could be put into effect. There was no obvious means, however, of effecting the improvement most desired, a satisfactory snowshoe for the ponies.

The work already accomplished was enormous. On the Polar Journey the ponies and dogs could now travel light for the first hundred and thirty geographical miles, when, at One Ton Camp, they would for the first time take their full loads: the advantage of being able to start again with full loads when so far on your way is obvious when it is considered that the distance travelled depends upon the weight of food that can be carried. During the geological journey on the western side of the Sound, Taylor and his party had carried out much useful geological work in Dry Valley and on the Ferrar and Koettlitz Glaciers, which had been accurately plotted for the charts, and had been examined for the first time by an expert physiographer and ice specialist. The ordinary routine of scientific and meteorological observations usual with all Scott’s sledging parties was observed.

Further, at Cape Evans there had been running for more than three months a scientific station, which rivalled in thoroughness and exactitude any other such station in the world. I hope that later a more detailed account may be given of this continuous series of observations, some of them demanding the most complex mechanism, and all of them watched over by enthusiastic experts. It must here suffice to say that we who on our return saw for the first time the hut and its annexes completely equipped were amazed; though perhaps the gadget which appealed most to us at first was the electric apparatus by which the cook, whose invention it was, controlled the rising of his excellent bread.

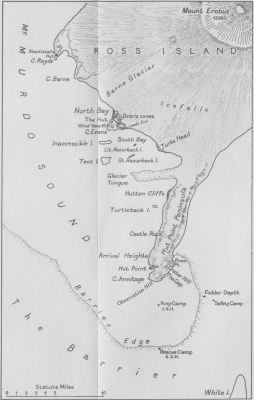

Glad as we were to find it all and to enjoy the food, bath and comfort which it offered, we had no illusions about Cape Evans itself. It is uninteresting, as only a low-lying spit of black lava covered for the most part with snow, and swept constantly by high winds and drift, can be uninteresting. The kenyte lava of which it is formed is a remarkable rock, and is found in few parts of the world: but when you have seen one bit of kenyte you have seen all. Unlike the spacious and lofty Hut Point Peninsula, thirteen miles to the south, it has no outstanding hills and craters; no landmarks such as Castle Rock. Unlike the broad folds of Cape Royds, six miles to the north, it has none of the rambling walks and varied lakes, in which is found most of the limited plant life which exists in these latitudes, and though a few McCormick skuas meet here, there is no nursery of penguins such as that which makes Cape Royds so attractive in summer. Nor has the Great Ice Sheet, which reached up Erebus and spread over the Ross Sea in the past, spilled over Cape Evans in its retreat a wealth of foreign granites, dolerites, porphyrys and sandstone such as cover the otherwise dull surface round Shackleton’s old Winter Quarters.

Cape Evans is a low lava flow jutting out some three thousand feet from the face of the glaciers which clothe the slopes of Erebus. It is roughly an equilateral triangle in shape, at its base some three thousand feet (9/16th mile) across. This baseline, which divides the cape from the slopes of Erebus and the crevassed glaciers and giant icefalls which clothe them, consists of a ramp with a slope of thirty degrees, and a varying height of some 100 to 150 feet. From our hut, four hundred yards away, it looks like a great embankment behind which rises the majestic volcano Erebus, with its plume of steam and smoke.

The cape itself does not rise on the average more than thirty feet, and somewhat resembles the back of a hog with several backbones. The hollows between the ridges are for the most part filled with snow and ice, while in one or two places where the accumulation of snow is great enough there are little glacierets which do not travel far before they ignominiously peter out. There are two small lakes, called Skua Lake and Island Lake respectively. There is only one hill which is almost behind the hut, and is called Wind Vane Hill, for on it were placed one of our wind vanes and certain other meteorological instruments. Into the glacieret which flowed down in the lee of this hill we drove two caves, which gave both an even low temperature and excellent insulation. One of them was therefore used for our magnetic observations, and the other as an icehouse for the mutton we had brought from New Zealand.

The north side, upon which we had built our hut, slopes down by way of a rubbly beach to the sea in North Bay. We knew there was a beach for we landed upon it, but we never saw it again even in the height of summer, for the winter blizzards formed an ice foot several feet thick. The other side of the cape ends abruptly in black bastions and baby cliffs some thirty feet high. The apex of the triangle which forms as it were the cape proper is a similar kenyte bluff. The whole makes a tricky place on which to walk in the dark, for the surface is strewn with boulders of all sizes and furrowed and channelled by drifts of hard and icy snow, and quite suddenly you may find yourself prostrate upon a surface of slippery blue ice. It may be easily imagined that it is no seemly place to exercise skittish ponies or mules in a cold wind, but there is no other place when the sea-ice is unsafe.

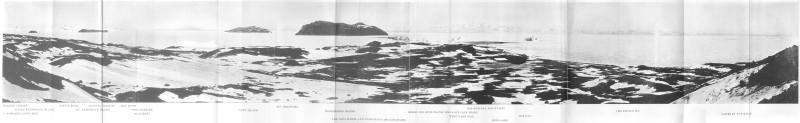

Come and stand outside the hut door. All round you, except where the cape joins the mountain, is the sea. You are facing north with your back to the Great Ice Barrier and the Pole, with your eyes looking out of the mouth of McMurdo Sound over the Ross Sea towards New Zealand, two thousand miles of open water, pack and bergs. Look over the sea to your left. It is midday, and though the sun will not appear above the horizon he is still near enough to throw a soft yellow light over the Western Mountains. These form the coastline thirty miles across the Sound, and as they disappear northwards are miraged up into the air and float, black islands in a lemon sky. Straight ahead of you there is nothing to be seen but black open sea, with a high light over the horizon, which you know betokens pack; this is ice blink. But as you watch there appears and disappears a little dark smudge. This puzzles you for some time, and then you realize that this is the mirage of some far mountain or of Beaufort Island, which guards the mouth of McMurdo Sound against such traffic as ever comes that way, by piling up the ice floes across the entrance.

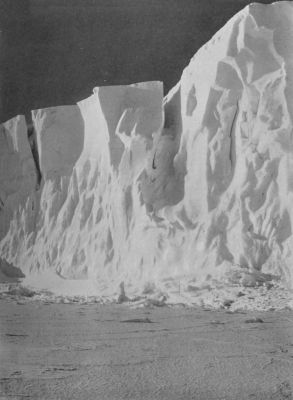

As you still look north, in the middle distance, jutting out into the sea, is a low black line of land, with one excrescence. This is Cape Royds, with Shackleton’s old hut upon it; the excrescence is High Peak, and this line marks the first land upon the eastern side of McMurdo Sound which you can see, and indeed is actually the most eastern point of Ross Island. It disappears abruptly behind a high wall, and if you let your eyes travel round towards your right front you see that the wall is a perpendicular cliff two hundred feet high of pure green and blue ice, which falls sheer into the sea, and forms, with Cape Evans, on which we stand, the bay which lies in front of our hut, and which we called North Bay. This great ice-cliff with its crevasses, towers, bastions and cornices, was a never-ending source of delight to us; it forms the snout of one of the many glaciers which slide down the slopes of Erebus: in smooth slopes and contours where the mountain underneath is of regular shape: in impassable icefalls where the underlying surface is steep or broken. This particular ice stream is called the Barne Glacier, and is about two miles across. The whole background from our right front to our right rear, that is from N. E. to S. E., is occupied by our massive and volcanic neighbour, Erebus. He stands 13,500 feet high. We live beneath his shadow and have both admiration and friendship for him, sometimes perhaps tinged with respect. However, there are no signs of dangerous eruptive disturbances in modern times, and we feel pretty safe, despite the fact that the smoke which issues from his crater sometimes rises in dense clouds for many thousands of feet, and at others the trail of his plume can be measured for at least a hundred miles.

If you are not too cold standing about (it does not pay to stand about at Cape Evans) let us make our way behind the hut and up Wind Vane Hill. This is only some sixty-five feet high, yet it dominates the rest of the cape and is steep enough to require a scramble, even now when the wind is calm. Look out that you do not step on the electric wires which connect the wind-vane cups on the hill with the recording dial in the hut. These cups revolve in the wind, the revolutions being registered electrically: every four miles a signal was sent to the hut, and a pen working upon a chronograph registered one more step. There is also a meteorological screen on the summit, which has to be visited at eight o’clock each morning in all weathers.

Arrived on the top you will now be facing south, that is in the opposite direction to which you were facing before. The first thing that will strike you is that the sea, now frozen in the bays though still unfrozen in the open sound, flows in nearly to your feet. The second, that though the sea stretches back for nearly twenty miles, yet the horizon shows land or ice in every direction. For a ship this is a cul-de-sac, as Ross found seventy years ago. But as soon as you have grasped these two facts your whole attention will be riveted to the amazing sight on your left. Here are the southern slopes of Erebus; but how different from those which you have lately seen. Northwards they fell in broad calm lines to a beautiful stately cliff which edged the sea. But here—all the epithets and all the adjectives which denote chaotic immensity could not adequately tell of them. Visualize a torrent ten miles long and twenty miles broad; imagine it falling over mountainous rocks and tumbling over itself in giant waves; imagine it arrested in the twinkling of an eye, frozen and white. Countless blizzards have swept their drifts over it, but have failed to hide it. And it continues to move. As you stand in the still cold air you may sometimes hear the silence broken by the sharp reports as the cold contracts it or its own weight splits it. Nature is tearing up that ice as human beings tear paper.

The sea-cliff is not so high here, and is more broken up by crevasses and caves, and more covered with snow. Some five miles along the coast the white line is broken by a bluff and black outcrop of rock; this is Turk’s Head, and beyond it is the low white line of Glacier Tongue, jutting out for miles into the sea. We know, for we have already crossed it, that there is a small frozen bay of sea-ice beyond, but all we can see from Cape Evans is the base of the Hut Point Peninsula, with a rock outcrop just showing where the Hutton Cliffs lie. The Peninsula prevents us from seeing the Barrier, though the Barrier wind is constantly flowing over it, as the clouds of drift now smoking over the Cliffs bear witness. Farther to the right still, the land is clear: Castle Rock stands up like a sentinel, and beyond are Arrival Heights and the old craters we have got to know so well during our stay at Hut Point. The Discovery hut, which would, in any case, be invisible at fifteen miles, is round that steep rocky corner which ends the Peninsula, due south from where we stand.

There remains undescribed the quadrant which stretches to our right front from south to west. Just as we have previously seen the line of the Western Mountains disappearing to the north miraged up in the light of the midday sun, so now we see the same line of mountains running south, with many miles of sea or Barrier between us and them. On the far southern horizon, almost in transit with Hut Point, stands Minna Bluff, some ninety miles away, beyond which we have laid the One Ton Depot, and from this point, as our eyes move round to the right, we see peak after peak of these great mountain ranges—Discovery, Morning, Lister, Hooker, and the glaciers which divide them one from another. They rise almost without a break to a height of thirteen thousand feet. Between us and them is the Barrier to the south, and the sea to the north. Unless a blizzard is impending or blowing, they are clearly visible, a gigantic wall of snow and ice and rock, which bounds our view to the west, constantly varied by the ever-changing colour of the Antarctic. Beyond is the plateau.

We have not yet mentioned four islands which lie within a radius of about three miles from where we stand. The most important is a mile from the end of Cape Evans and is called Inaccessible Island, owing to the inhospitality of its steep lava side, even when the sea is frozen; we found a way up, but it is not a very interesting place. Tent Island lies farther out and to the southwest. The remaining two, which are more islets than islands, rise in front of us in South Bay. They are called Great and Little Razorback, being ribs of rock with a sharp divide in the centre. The latter of these is the refuge upon which Scott’s party returning to Cape Evans pitched their camp when overtaken by a blizzard some weeks ago. All these islands are of volcanic origin and black in general colour, but I believe there is evidence to show that the lava stream which created them flowed from McMurdo Sound rather than from the more obvious craters of Erebus. Their importance in this story is the indirect help they gave in holding in sea-ice against southerly blizzards, and in forming landmarks which proved useful more than once to men who had lost their bearings in darkness and thick weather. In this respect also several icebergs which sailed in from the Ross Sea and grounded on the shallows which run between Inaccessible Island and the cape, as well as in South Bay, were most useful as well as being interesting and beautiful. For two years we watched the weathering of these great towers and bastions of ice by sea and sun and wind, and left them still lying in the same positions, but mere tumbled ruins of their former selves.

Many places in the panorama we have examined show black rock, and the cape on which we stand exposes at times more black than white. This fact always puzzles those who naturally conclude that all the Antarctic is covered with ice and snow. The explanation is simple, that winds of the great velocity which prevails in this region will not only prevent snow resting to windward of outcropping rocks and cliffs, but will even wear away the rocks themselves. The fact that these winds always blow from the south, or southerly, causes a tendency for this aspect of any projecting rock to be blown free from snow, while the north or lee side is drifted up by a marbled and extremely hard tongue of snow, which disappears into a point at a distance which depends upon the size of the rock.

Of course for the most part the land is covered to such a depth by glaciers and snow that no wind will do more than pack the snow or expose the ice beneath. At the same time, to visualize the Antarctic as a white land is a mistake, for, not only is there much rock projecting wherever mountains or rocky capes and islands rise, but the snow seldom looks white, and if carefully looked at will be found to be shaded with many colours, but chiefly with cobalt blue or rose-madder, and all the gradations of lilac and mauve which the mixture of these colours will produce. A White Day is so rare that I have recollections of going out from the hut or the tent and being impressed by the fact that the snow really looked white. When to the beautiful tints in the sky and the delicate shading on the snow are added perhaps the deep colours of the open sea, with reflections from the ice foot and ice-cliffs in it, all brilliant blues and emerald greens, then indeed a man may realize how beautiful this world can be, and how clean.

Though I may struggle with inadequate expression to show the reader that this pure Land of the South has many gifts to squander upon those who woo her, chiefest of these gifts is that of her beauty. Next, perhaps, is that of grandeur and immensity, of giant mountains and limitless spaces, which must awe the most casual, and may well terrify the least imaginative of mortals. And there is one other gift which she gives with both hands, more prosaic, but almost more desirable. That is the gift of sleep. Perhaps it is true of others as is certainly the case with me, that the more horrible the conditions in which we sleep, the more soothing and wonderful are the dreams which visit us. Some of us have slept in a hurricane of wind and a hell of drifting snow and darkness, with no roof above our heads, with no tent to help us home, with no conceivable chance that we should ever see our friends again, with no food that we could eat, and only the snow which drifted into our sleeping-bags which we could drink day after day and night after night. We slept not only soundly the greater part of these days and nights, but with a certain numbed pleasure. We wanted something sweet to eat: for preference tinned peaches in syrup! Well! That is the kind of sleep the Antarctic offers you at her worst, or nearly at her worst. And if the worst, or best, happens, and Death comes for you in the snow, he comes disguised as Sleep, and you greet him rather as a welcome friend than as a gruesome foe. She treats you thus when you are in the extremity of peril and hardship; perhaps then you can imagine what draughts of deep and healthy slumber she will give a tired sledger at the end of a long day’s march in summer, when after a nice hot supper he tucks his soft dry warm furry bag round him with the light beating in through the green silk tent, the homely smell of tobacco in the air, and the only noise that of the ponies tethered outside, munching their supper in the sun.

And so it came about that during our sojourn at Cape Evans, in our comfortable warm roomy home, we took our full allotted span of sleep. Most were in their bunks by 10 p.m., sometimes with a candle and a book, not rarely with a piece of chocolate. The acetylene was turned off at 10:30, for we had a limited quantity of carbide, and soon the room was in complete darkness, save for the glow of the galley stove and where a splash of light showed the night watchman preparing his supper. Some snored loudly, but none so loud as Bowers; others talked in their sleep, the more so when some nasty experience had lately set their nerves on edge. There was always the ticking of many instruments, and sometimes the ring of a little bell: to this day I do not know what most of them meant. On a calm night no sound penetrated except, perhaps, the whine of a dog, or the occasional kick of a pony in the stable outside. Any disturbance was the night watchman’s job. But on a bad blizzard night the wind, as it tore seawards over the hut, roared and howled in the ventilator let into the roof: in the more furious gusts the whole hut shook, and the pebbles picked up by the hurricane scattered themselves noisily against the woodwork of the southern wall. We did not get many nights like these the first winter; during the second we seemed to get nothing else. One ghastly blizzard blew for six weeks.

The night watchman took his last hourly observation at 7 a.m., and was free to turn in after waking the cook and making up the fire. Frequently, however, he had so much work to do that he preferred to forgo his sleep and remain up. For instance, if the weather looked threatening, he would take his pony out for exercise as soon as possible in the morning, or those lists of stores were not finished, or that fish trap had to be looked after: all kinds of things.

A sizzling on the fire and a smell of porridge and fried seal liver heralded breakfast, which was at 8 a.m. in theory and a good deal later in practice. A sleepy eye might see the meteorologist stumping out (Simpson always stumped) to change the records in his magnetic cave and visit his instruments on the Hill. Twenty minutes later he would be back, as often as not covered with drift and his wind helmet all iced up. Meanwhile, the more hardy ones were washing: that is, they rubbed themselves, all shivering, with snow, of a minus temperature, and pretended they liked it. Perhaps they were right, but we told them it was swank. I’m not sure that it wasn’t! It should be explained that water was seldom possible in a land where ice is more abundant than coal.

One great danger threatened all our meals in this hut, namely that of a Cag. A Cag is an argument, sometimes well informed and always heated, upon any subject under the sun, or temporarily in our case, the moon. They ranged from the Pole to the Equator, from the Barrier to Portsmouth Hard and Plymouth Hoe. They began on the smallest of excuses, they continued through the widest field, they never ended; they were left in mid air, perhaps to be caught up again and twisted and tortured months after. What caused the cones on the Ramp; the formation of ice crystals; the names and order of the public-houses if you left the Main Gate of Portsmouth Dockyard and walked to the Unicorn Gate (if you ever reached so far); the best kinds of crampons in the Antarctic, and the best place in London for oysters; the ideal pony rug; would the wine steward at the Ritz look surprised if you asked him for a pint of bitter? Though the Times Atlas does not rise to public-houses nor Chambers’s Encyclopaedia sink to behaviour at our more expensive hotels, yet they settled more of these disputes than anything else.

On the day we are discussing, though mutterings can still be heard from Nelson’s cubicle, the long table has been cleared and everyone is busy by 9:30. From now until supper at 7 work is done by all in some form or other, except for a short luncheon interval. I do not mean for a minute that we all sit down, as a man may do in an office at home, and solidly grind away for upwards of nine hours or more. Not a bit of it. We have much work out of doors, and exercise is a consideration of the utmost importance. But when we go out, each individual quite naturally takes the opportunity to carry out such work as concerns him, whether it deals with ice or rocks, dogs or horses, meteorology or biology, tide-gauges or balloons.

When blizzards allowed, the ponies were exercised by their respective leaders between breakfast and midday, when they were fed. This exercising of animals might be a pleasant business, on the other hand it could be the deuce and all: it depended on the pony and the weather. A blubber fire was kept burning in the snug stable, which was built against the lee wall of the hut: the ponies were, therefore, quite warm, and found it chilly directly they were led outside, even if there was no wind.

The difficulties of exercising them in the dark were so great that with the best intentions in the world it was difficult to give them sufficient work for the good feeding they received. Add to this the fact that one at any rate of these variable animals was really savage, and that most of them were keen to break away if possible, and the hour of exercise was not without its thrills even on the calmest and most moonlight days. The worst days were those when it was difficult to say whether the ponies should be taken out on the sea-ice or not. It was thick weather that was to be feared, for then, if the leader once lost his bearings, it was most difficult for him to return. An overcast sky, light falling snow, perhaps a light northerly wind generally meant a blizzard, but the blizzard might not break for twenty-four hours, it might be upon you in four seconds. It was difficult to say whether the pony should miss his exercise, whether the fish trap should be raised, whether to put off your intended trip to Cape Royds. Generally the risks were taken, for, on the whole, it is better to be a little overbold than a little overcautious, while always there was a something inside urging you to do it just because there was a certain risk, and you hardly liked not to do it. It is so easy to be afraid of being afraid!

Let me give one instance: it must be typical of many. It was thick as it could be, no moon, no stars, light falling snow, and not even a light breeze to keep in your face to give direction. Bowers and I decided to take our ponies out, and once over the tide crack, where the working sea-ice joins the fast land-ice, we kept close under the tall cliffs of the Barne Glacier. So far all was well, and also when we struck along a small crack into the middle of the bay, where there was a thermometer screen. This we read with some difficulty by the light of a match and started back towards the hut. In about a quarter of an hour we knew we were quite lost until an iceberg which we recognized showed us that we had been walking at right angles to our course, and got us safe home.

On a clear crisp day, with the full moon to show you the ridges and cracks and sastrugi, it was most pleasant to put on your ski and wander forth with no object but that of healthy pleasure. Perhaps you would make your way round the bluff end of the cape and strike southwards. Here you may visit Nelson working with his thermometers and current meters and other instruments over a circular hole in the ice, which he keeps open from day to day by breaking out the “biscuit” of newly formed ice. He has connected himself with the hut by telephone, and built round himself an igloo of drifted snow and the aforesaid “biscuits,” which effectually shelter him from the wind. Or you may meet Meares and Dimitri returning with the dog-teams from a visit to Hut Point. A little farther on the silence is complete. But now your ear catches the metallic scratch of ski sticks on hard ice; there is someone else skiing over there, it may be many miles away, for sound travels in an amazing way. Every now and then there comes a sharp crack like a pistol shot; it is the ice contracting in the glaciers of Erebus, and you know that it is getting colder. Your breath smokes, forming white rime over your face, and ice in your beard; if it is very cold you may actually hear it crackle as it freezes in mid air!

These were the days which remain visibly in the mind as the most enjoyable during this first winter season. It was all so novel, these much-dreaded, and amongst us much-derided, terrors of the Long Winter Night. The atmosphere is very clear when it is not filled with snow or ice crystals, and the moonlight lay upon the land so that we could see the main outlines of the Hut Point Peninsula, and even Minna Bluff out on the Barrier ninety miles away. The ice-cliffs of Erebus showed as great dark walls, but above them the blue ice of the glaciers gleamed silvery, and the steam flowed lazily from the crater carried away in a long line, showing us that the northerly breezes prevailed up there, and were storing up trouble in the south. Sometimes a shooting star would seem to fall right into the mountain, and for the most part the Aurora flitted uneasily about in the sky.

The importance of plenty of outdoor exercise was generally recognized, and our experience showed us that the happiest and healthiest members of our party during this first year were those who spent the longest period in the fresh air. As a rule we walked and worked and skied alone, not I feel sure because of any individual distaste for the company of our fellows but rather because of a general inclination to spend a short period of the day without company. At least this is certainly true of the officers: I am not so sure about the men. Under the circumstances, the only time in the year that a man could be alone was in his walks abroad from Winter Quarters, for the hut, of course, was always occupied, and when sledging this sardine-like existence was continuous night and day.

There was one regular exception to this rule. Every possible evening, that is to say if it was not blowing a full blizzard, Wilson and Bowers went up the Ramp together “to read Bertram.” Now this phrase will convey little meaning without some explanation. I have already spoken of the Ramp as the steep rubbly slope partly covered by snow and partly by ice which divided the cape on which we lived from the glaciated slopes of Erebus. After a breathless scramble up this embankment one came upon a belt of rough boulder-strewn ground from which arose at intervals conical mounds, the origin of which puzzled us for many months. At length, by the obvious means of cutting a section through one of them, it was proved that there was a solid kenyte lava block in the centre of this cone, proving that the whole was formed by the weathering of a single rock. Threading your way for some hundreds of yards through this terrain, a scramble attended by many slips and falls on a dark night, you reached the first signs of glaciation. A little farther, isolated in the ice stream, is another group of debris cones, and on the largest of these we placed meteorological Screen “B,” commonly called Bertram. This screen, together with “A” (Algernon) and “C” (Clarence), which were in North and South Bays respectively, were erected by Bowers, who thought, rightly, that they would form an object to which men could guide their walks, and that at the same time the observations of maximum, minimum and present temperatures would be a useful check to the meteorologist when he came to compare them with those taken at the hut. As a matter of fact the book in which we used to enter these observations shows that the air temperatures out on the sea-ice vary considerably from those on the cape, and that the temperatures several hundred feet up on the slopes of Erebus are often several degrees higher than those taken at sea-level. I believe that much of the weather in this part of the world is an intensely local affair, and these screens produced useful data.

Wilson and Bowers would go up the Ramp when it was blowing and drifting fairly hard, so that although the rocks and landmarks immediately round them were visible, all beyond was blotted out. It is quite possible to walk thus among landmarks which you know at a time when it is most unwise to go out on to the sea-ice where there are no fixed points to act as a guide.

It was Wilson’s pleasant conceit to keep his balaclava rolled up, so that his face was bare, on such occasions, being somewhat proud of the fact that he had not, as yet, been frostbitten. Imagine our joy when he entered the hut one cold windy evening with two white spots on his cheeks which he vainly tried to hide behind his dogskin mitts.

The ponies’ lunch came at midday, when they were given snow to drink and compressed fodder with oats or oil-cake on alternate days to eat, the proportion of which was arranged according to the work they were able to do in the present, or expected to do in the future. Our own lunch was soon after one, and a few minutes before that time Hooper’s voice would be heard: “Table please, Mr. Debenham,” and all writing materials, charts, instruments and books would have to be removed. On Sunday, this table displayed a dark blue cloth, but for meals and at all other times it was covered with white oilcloth.

Lunch itself was a pleasant meatless meal, consisting of limited bread and butter with plenty of jam or cheese, tea or cocoa, the latter being undoubtedly a most useful drink in a cold country. Many controversies raged over the rival merits of tea and cocoa. Some of us made for ourselves buttered toast at the galley fire; I must myself confess to a weakness for Welsh Rarebit, and others followed my example on cheese days in making messes of which we were not a little proud. Scott sat at the head of the table, that is at the east end, but otherwise we all took our places haphazard from meal to meal as our conversation, or want of it, merited, or as our arrival found a vacant chair. Thus if you felt talkative you might always find a listener in Debenham; if inclined to listen yourself it was only necessary to sit near Taylor or Nelson; if, on the other hand, you just wanted to be quiet, Atkinson or Oates would, probably, give you a congenial atmosphere.

There was never any want of conversation, largely due to the fact that no conversation was expected: we most of us know the horrible blankness which comes over our minds when we realize that because we are eating we are also supposed to talk, whether we have anything to say or not. It was also due to the more primitive reason that in a company of specialists, whose travels extended over most parts of the earth, and whose subjects overlapped and interlocked at so many points, topics of conversation were not only numerous but full of possibilities of expansion. Add to this that from the nature of our work we were probably people of an inquisitive turn of mind and wanted to get to the bottom of the subjects which presented themselves, and you may expect to find, as was in fact the case, an atmosphere of pleasant and quite interesting conversation which sometimes degenerated into heated and noisy argument.

The business of eating over, pipes were lit without further formality. I mention pipes only because while we had a most bountiful supply of tobacco, the kindly present of Mr. Wills, our supply of cigarettes from the same source was purposely limited and only a small quantity were landed, allowing of a ration to such members who wished. Consequently cigarettes were an article of some value, and in a land where the ordinary forms of currency are valueless they became a frequent stake to venture when making bets. Indeed, “I bet you ten cigarettes,” or “I bet you a dinner when we get back to London,” became the most frequent bids of the argumentative gambler, occasionally varied when the bettor was more than usually certain of the issue by the offer of a pair of socks.

By two o’clock we were dispersed once more to our various works and duties. If it was bearable outside, the hut would soon be empty save for the cook and a couple of seamen washing up the plates; otherwise everyone went out to make the most of any glimmering of daylight which still came to us from the sun below the northern horizon. And here it may be explained that whereas in England the sun rises more or less in the east, is due south at midday, and sets in the west, this is not the case in the Antarctic regions. In the latitude in which we now lived the sun is at his highest at midday in the north, at his lowest at midnight in the south. As is generally known he remains entirely above the horizon for four months of the summer (October-February) and entirely below the horizon for four months in the winter (April 21-August 21). About February 27, the end of summer, he begins to set and rise due south at midnight; the next day he sets a little earlier and dips a little deeper. During March and April he is going deeper and deeper every day, until, by the middle of April, he is set all the time except for just a peep over the northern horizon at midday, which is his last farewell before he goes away.

The reverse process takes place from August 21 onwards. On this date the sun just peeped above the sea to the north of our hut. The next day he rose a little higher and longer, and in a few weeks he was rising well in the east and sinking behind the Western Mountains. But he did not stop there. Soon he was rising in the S. E. until in the latter days of September he never rose, for he never set; but circled round us by day and night. On Midsummer Day (December 21) at the South Pole the sun circles round for twenty-four hours without changing his altitude for one minute of a degree, but elsewhere he is always rising in the sky until midday in the north and falling from that time until midnight in the south.

Often, far too often, it was blizzing, and it was impossible to go out except into the camp to take the observations, to care for the dogs, to get ice for water or to bring in stores. Even a short excursion of a few yards had to be made with great care under such circumstances, and certainly no one went outside more than was necessary, if only because one was obliged to dig the accumulated drift from the door before it was possible to proceed. Blizzard or no blizzard, most men were back in the hut soon after four, and from then until 6:30 worked steadily at their jobs. As supper time approached some kindly-disposed person would sit down and play on the Broadwood pianola which was one of our blessings, and so it was that we came to supper with good tempers as well as keen appetites.

Soup, in which the flavour of tomatoes occurred all too frequently, followed by seal or penguin, and twice a week by New Zealand mutton, with tinned vegetables, formed the basis of our meal, and this was followed by a pudding. We drank lime juice and water which sometimes included a suspicious penguin flavour derived from the ice slopes from which our water was quarried.

During our passage out to New Zealand in the ship (or as Meares always insisted on calling her, the steamer) it was our pleasant custom to have a glass of port or a liqueur after dinner. Alas, we had this no longer: after leaving New Zealand space allowed of little wine being carried in the Terra Nova, even if the general medical opinion of the expedition had not considered its presence undesirable. We had, however, a few cases for special festivals, as well as some excellent liqueur brandy which was carried as medical comforts on our sledge journeys. Any officer who allowed the distribution of this luxury on nearing the end of a journey became extremely popular.

Lack of wine probably led to the suspension of a custom which had prevailed on the Terra Nova, namely, the drinking of the old toast of Saturday night, “Sweethearts and wives; may our sweethearts become our wives, and our wives remain our sweethearts,” and that more appropriate (in our case) toast of Sunday, namely, “absent friends.” We had but few married officers, though I must say most survivors of the expedition hurried to remedy this single state of affairs when they returned to civilization. Only two of them are unmarried now. Most of them will probably make a success of it, for the good Arctic explorer has most of the defects and qualities of a good husband.

On the top of the pianola, close to the head of the table, lived the gramophone; and under the one looking-glass we possessed, which hung on the bulkhead of Scott’s cubicle, was a homemade box with shelves on which lay our records. It was usual to start the gramophone after dinner, and its value may be imagined. It is necessary to be cut off from civilization and all that it means to enable you to realize fully the power music has to recall the past, or the depths of meaning in it to soothe the present and give hope for the future. We had also records of good classical music, and the kindly-disposed individual who played them had his reward in the pleasant atmosphere of homeliness which made itself felt. After dinner had been cleared away, some men sat on at the table occupied with books and games. Others dispersed to various jobs. In the matter of games it was noticeable that one would have its vogue and yield place to another without any apparent reason. For a few weeks it might be chess, which would then yield its place to draughts and backgammon, and again come into favour. It is a remarkable fact that, though we had playing cards with us none of our company appeared desirous to use them. In fact I cannot remember seeing a game of cards played except in the ship on the voyage from England.

With regard to books we were moderately well provided with good modern fiction, and very well provided with such authors as Thackeray, Charlotte Brontë, Bulwer-Lytton and Dickens. With all respect to the kind givers of these books, I would suggest that the literature most acceptable to us in the circumstances under which we did most of our reading, that is in Winter Quarters, was the best of the more recent novels, such as Barrie, Kipling, Merriman and Maurice Hewlett. We certainly should have taken with us as much of Shaw, Barker, Ibsen and Wells as we could lay our hands on, for the train of ideas started by these works and the discussions to which they would have given rise would have been a godsend to us in our isolated circumstances. The one type of book in which we were rich was Arctic and Antarctic travel. We had a library of these given to us by Sir Lewis Beaumont and Sir Albert Markham which was very complete. They were extremely popular, though it is probably true that these are books which you want rather to read on your return than when you are actually experiencing a similar life. They were used extensively in discussions or lectures on such polar subjects as clothing, food rations, and the building of igloos, while we were constantly referring to them on specific points and getting useful hints, such as the use of an inner lining to our tents, and the mechanism of a blubber stove.

I have already spoken of the importance of maps and books of reference, and these should include a good encyclopaedia and dictionaries, English, Latin and Greek. Oates was generally deep in Napier’s History of the Peninsular War, and some of us found Herbert Paul’s History of Modern England a great standby. Most of us managed to find room in our personal gear when sledging for some book which did not weigh much and yet would last. Scott took some Browning on the Polar Journey, though I only saw him reading it once; Wilson took Maud and In Memoriam; Bowers always had so many weights to tally and observations to record on reaching camp that I feel sure he took no reading matter. Bleak House was the most successful book I ever took away sledging, though a volume of poetry was useful, because it gave one something to learn by heart and repeat during the blank hours of the daily march, when the idle mind is all too apt to think of food in times of hunger, or possibly of purely imaginary grievances, which may become distorted into real foundations of discord under the abnormal strain of living for months in the unrelieved company of three other men. If your companions have much the same tastes as yourself it is best to pool your allowance of weights and take one book which will offer a wide field of thought and discussion. I have heard Scott and Wilson bless the thought which led them to take Darwin’s Origin of Species on their first Southern Journey. Such is the object of your sledging book, but you often want the book which you read for half an hour before you go to sleep at Winter Quarters to take you into the frivolous fripperies of modern social life which you may not know and may never wish to know, but which it is often pleasant to read about, and never so much so as when its charms are so remote as to be entirely tantalizing.

Scott, who always amazed me by the amount of work he got through without any apparent effort, was essentially the driving force of the expedition: in the hut quietly organizing, working out masses of figures, taking the greatest interest in the scientific work of the station, and perhaps turning out, quite by the way, an elaborate paper on an abstruse problem in the neighbourhood; fond of his pipe and a good book, Browning, Hardy (Tess was one of his favourites), Galsworthy. Barrie was one of his greatest friends.

He was eager to accept suggestions if they were workable, and always keen to sift even the most unlikely theories if by any means they could be shaped to the desired end: a quick and modern brain which he applied with thoroughness to any question of practice or theory. Essentially an attractive personality, with strong likes and dislikes, he excelled in making his followers his friends by a few words of sympathy or praise: I have never known anybody, man or woman, who could be so attractive when he chose.

Sledging he went harder than any man of whom I have ever heard. Men never realized Scott until they had gone sledging with him. On our way up the Beardmore Glacier we were going at top pressure some seventeen hours out of the twenty-four, and when we turned out in the morning we felt as though we had only just turned in. By lunch time we felt that it was impossible to get through in the afternoon a similar amount of work to that which we had done in the morning. A cup of tea and two biscuits worked wonders, and the first two hours of the afternoon’s march went pretty well, indeed they were the best hours’ marching of the day; but by the time we had been going some 4½ or 5 hours we were watching Scott for that glance to right and left which betokened the search for a good camping site. “Spell oh!” Scott would cry, and then “How’s the enemy, Titus?” to Oates, who would hopefully reply that it was, say, seven o’clock. “Oh, well, I think we’ll go on a little bit more,” Scott would say. “Come along!” It might be an hour or more before we halted and made our camp: sometimes a blizzard had its silver lining. Scott could not wait. However welcome a blizzard could be to tired bodies (I speak only of summer sledging), to Scott himself any delay was intolerable. And it is hard to realize how difficult waiting may be to one in a responsible position. It was our simple job to follow, to get up when we were roused, to pull our hardest, to do our special work as thoroughly and quickly as possible; it was Scott who had to organize distances and weights and food, as well as do the same physical work as ourselves. In sledging responsibility and physical work are combined to an extent seldom if ever found elsewhere.

His was a subtle character, full of lights and shades.

England knows Scott as a hero; she has little idea of him as a man. He was certainly the most dominating character in our not uninteresting community: indeed, there is no doubt that he would carry weight in any gathering of human beings. But few who knew him realized how shy and reserved the man was, and it was partly for this reason that he so often laid himself open to misunderstanding.

Add to this that he was sensitive, femininely sensitive, to a degree which might be considered a fault, and it will be clear that leadership to such a man may be almost a martyrdom, and that the confidence so necessary between leader and followers, which must of necessity be based upon mutual knowledge and trust, becomes in itself more difficult. It wanted an understanding man to appreciate Scott quickly; to others knowledge came with experience.

He was not a very strong man physically, and was in his youth a weakly child, at one time not expected to live. But he was well proportioned, with broad shoulders and a good chest, a stronger man than Wilson, weaker than Bowers or Seaman Evans. He suffered from indigestion, and told me at the top of the Beardmore that he never expected to go on during the first stage of the ascent.

Temperamentally he was a weak man, and might very easily have been an irritable autocrat. As it was he had moods and depressions which might last for weeks, and of these there is ample evidence in his diary. The man with the nerves gets things done, but sometimes he has a terrible time in doing them. He cried more easily than any man I have ever known.

What pulled Scott through was character, sheer good grain, which ran over and under and through his weaker self and clamped it together. It would be stupid to say he had all the virtues: he had, for instance, little sense of humour, and he was a bad judge of men. But you have only to read one page of what he wrote towards the end to see something of his sense of justice. For him justice was God. Indeed I think you must read all those pages; and if you have read them once, you will probably read them again. You will not need much imagination to see what manner of man he was.

And notwithstanding the immense fits of depression which attacked him, Scott was the strongest combination of a strong mind in a strong body that I have ever known. And this because he was so weak! Naturally so peevish, highly strung, irritable, depressed and moody. Practically such a conquest of himself, such vitality, such push and determination, and withal in himself such personal and magnetic charm. He was naturally an idle man, he has told us so;134 he had been a poor man, and he had a horror of leaving those dependent upon him in difficulties. You may read it over and over again in his last letters and messages.135

He will go down to history as the Englishman who conquered the South Pole and who died as fine a death as any man has had the honour to die. His triumphs are many—but the Pole was not by any means the greatest of them. Surely the greatest was that by which he conquered his weaker self, and became the strong leader whom we went to follow and came to love.

Scott had under him this first year in his Main Party a total of 15 officers and 9 men. These officers may be divided into three executive officers and twelve scientific staff, but the distinction is very rough, inasmuch as a scientist such as Wilson was every bit as executive as anybody else, and the executive officers also did much scientific work. I will try here briefly to give the reader some idea of the personality and activities of these men as they work any ordinary day in the hut. It should be noticed that not all the men we had with us were brought to do sledging work. Some were chosen rather for their scientific knowledge than for their physical or other fitness for sledging. The regular sledgers in this party of officers were Scott, Wilson, Evans, Bowers, Oates (ponies), Meares (dogs), Atkinson (surgeon), Wright (physicist), Taylor (physiographer), Debenham (geologist), Gran and myself, while Day was to drive his motors as far as they would go on the Polar Journey. This leaves Simpson, who was the meteorologist and whose observations had of necessity to be continuous; Nelson, whose observations into marine biology, temperatures of sea, salinity, currents and tides came under the same heading; and Ponting, whose job was photography, and whose success in this art everybody recognizes.

However much of good I may write of Wilson, his many friends in England, those who served with him on the ship or in the hut, and most of all those who had the good fortune to sledge with him (for it is sledging which is far the greatest test) will all be dissatisfied, for I know that I cannot do justice to his value. If you knew him you could not like him: you simply had to love him. Bill was of the salt of the earth. If I were asked what quality it was before others that made him so useful, and so lovable, I think I should answer that it was because he never for one moment thought of himself. In this respect also Bowers, of whom I will speak in a moment, was most extraordinary, and in passing may I be allowed to say that this is a most necessary characteristic of a good Antarctic traveller? We had many such, officers and seamen, and the success of the expedition was in no small measure due to the general and unselfish way in which personal likes and dislikes, wishes or tastes were ungrudgingly subordinated to the common weal. Wilson and Pennell set an example of expedition first and the rest nowhere which others followed ungrudgingly: it pulled us through more than one difficulty which might have led to friction.

Wilson was a man of many parts. He was Scott’s right-hand man, he was the expedition’s Chief of the Scientific Staff: he was a doctor of St. George’s Hospital, and a zoologist specializing in vertebrates. His published work on whales, penguins and seals contained in the Scientific Report of the Discovery Expedition is still the best available, and makes excellent reading even to the nonscientist. On the outward journey of the Terra Nova he was still writing up his work for the Royal Commission on Grouse Disease, the published report of which he never lived to see. But those who knew him best will probably remember Wilson by his watercolour paintings rather than by any other form of his many-sided work.

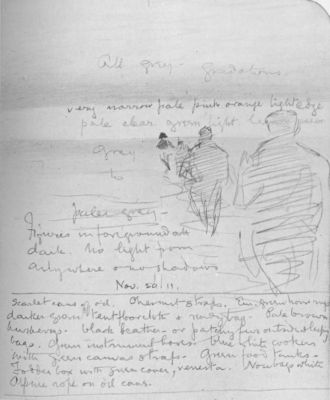

As a boy his father sent him away on rambling holidays, the only condition being that he should return with a certain number of drawings. I have spoken of the drawings which he made when sledging or when otherwise engaged away from painting facilities, as at Hut Point. He brought back to Winter Quarters a notebook filled with such sketches of outlines and colours: of sunsets behind the Western Mountains: of lights reflected in the freezing sea or in the glass houses of the ice foot: of the steam clouds on Erebus by day and of the Aurora Australis by night. Next door to Scott he rigged up for himself a table, consisting of two venesta cases on end supporting a large drawing-board some four feet square. On this he set to work systematically to paint the effects which he had seen and noted. He painted with his paper wet, and necessarily therefore, he worked quickly. An admirer of Ruskin, he wished to paint what he saw as truly as possible. If he failed to catch the effect he wished, he tore up the picture however beautiful the result he had obtained. There is no doubt as to the faithfulness of his colouring: the pictures recalled then and will still recall now in intimate detail the effects which we saw together. As to the accuracy of his drawing it is sufficient to say that in the Discovery Expedition Scott wrote on his Southern Journey:

“Wilson is the most indefatigable person. When it is fine and clear, at the end of our fatiguing days he will spend two or three hours seated in the door of the tent, sketching each detail of the splendid mountainous coast-scene to the west. His sketches are most astonishingly accurate; I have tested his proportions by actual angular measurement and found them correct.”136

In addition to the drawings of land, pack, icebergs and Barrier, the primary object of which was scientific and geographical, Wilson has left a number of paintings of atmospheric phenomena which are not only scientifically accurate but are also exceedingly beautiful. Of such are the records of auroral displays, parhelions, paraselene, lunar halos, fog bows, irridescent clouds, refracted images of mountains and mirage generally. If you look at a picture of a parhelion by Wilson not only can you be sure that the mock suns, circles and shafts appeared in the sky as they are shown on paper, but you can also rest assured that the number of degrees between, say, the sun and the outer ring of light were in fact such as he has represented them. You can also be certain in looking at his pictures that if cirrus cloud is shown, then cirrus and not stratus cloud was in the sky: if it is not shown, then the sky was clear. It is accuracy such as this which gives an exceptional value to work viewed from a scientific standpoint. Mention should also be made of the paintings and drawings made constantly by Wilson for the various specialists on the expedition whenever they wished for colour records of their specimens; in this connection the paintings of fish and various parasites are especially valuable.

I am not specially qualified to judge Wilson from the artistic point of view. But if you want accuracy of drawing, truth of colour, and a reproduction of the soft and delicate atmospheric effects which obtain in this part of the world, then you have them here. Whatever may be said of the painting as such, it is undeniable that an artist of this type is of inestimable value to an expedition which is doing scientific and geographical work in a little-known part of the earth.

Wilson himself set a low value on his artistic capacity. We used to discuss what Turner would have produced in a land which offered colour effects of such beauty. If we urged him to try and paint some peculiar effect and he felt that to do so was beyond his powers he made no scruple of saying so. His colour is clear, his brushwork clean: and he handled sledging subjects with the vigour of a professional who knew all there was to be known about a sledging life.

Scott and Wilson worked hand in hand to further the scientific objects of the expedition. For Scott, though no specialist in any one branch, had a most genuine love of science. “Science—the rock foundation of all effort,” he wrote; and whether discussing ice problems with Wright, meteorology with Simpson, or geology with Taylor, he showed not only a mind which was receptive and keen to learn, but a knowledge which was quick to offer valuable suggestions. I remember Pennell condemning anything but scientific learning in dealing with the problems round us; “no guesswork” was his argument. But he emphatically made an exception of Scott, who had an uncanny knack of hitting upon a solution. Over and over again in his diary we can read of the interest he took in pure and applied science, and it is doubtful whether this side of an expedition in high northern or southern latitudes has ever been more fortunate in their leader.

Wilson’s own share in the scientific results is more obvious because he was the director of the work. But no published reports will give an adequate idea of the ability he showed in coordinating the various interests of a varied community, nor of the tact he displayed in dealing with the difficulties which arose. Above all his judgment was excellent, and Scott as well as the rest of us relied upon him to a very great extent. The value of judgment in a land where a wrong decision may mean disaster as well as loss of life is beyond all price; weather in which changes are most sudden is a case in point, also the state of sea-ice, the direction to be followed in difficult country when sledging, the best way of taking crevassed areas when they must be crossed, and all the ways by which the maximum of result may be combined with the minimum of danger in a land where Nature is sometimes almost too big an enemy to fight: all this wants judgment, and if possible experience. Wilson could supply both, for his experience was as wide as that of Scott, and I have constantly known Scott change his mind after a talk with Bill. For the rest I give quotations from Scott’s diary:

“He has had a hand in almost every lecture given, and has been consulted in almost every effort which has been made towards the solution of the practical or theoretical problems of our Polar world.”137

Again:

“Words must always fail me when I talk of Bill Wilson. I believe he really is the finest character I ever met—the closer one gets to him the more there is to admire. Every quality is so solid and dependable; cannot you imagine how that counts down here? Whatever the matter, one knows Bill will be sound, shrewdly practical, intensely loyal and quite unselfish. Add to this a wider knowledge of persons and things than is at first guessable, a quiet vein of humour and really consummate tact, and you have some idea of his values. I think he is the most popular member of the party, and that is saying much.”138

And at the end, when Scott himself lay dying, he wrote to Mrs. Wilson:

“I can do no more to comfort you, than to tell you that he died as he lived, a brave, true man—the best of comrades and staunchest of friends.”139

Physically Scott had been a delicate boy but developed into a strong man, 5 feet 9 inches in height, 11 stone 6 lbs. in weight, with a chest measurement of 39¼ inches. Wilson was not a particularly strong man. On leaving with the Discovery he was but lately cured of consumption, yet he went with Scott to his farthest South, and helped to get Shackleton back alive. Shackleton owed his life to those two. Wilson was of a slimmer, more athletic build, a great walker, 5 feet 10½ inches in height, 11 stones in weight, with a chest measurement of 36 inches. He was an ideal example of my contention, which I believe can be proved many times over to be a fact, that it is not strength of body but rather strength of will which carries a man farthest where mind and body are taxed at the same time to their utmost limit. Scott was 43 years of age at his death, and Wilson 39.

Bowers was of a very different build. Aged 28, he was only 5 feet 4 inches in height while his chest measurement (which I give more as a general guide to his physique than for any other reason) was 40 inches, and his weight 12 stones. He was recommended to Scott by Sir Clements Markham, who was dining one day with Captain Wilson-Barker on the Worcester, on which ship Bowers was trained. Bowers was then home from India, and the talk turned to the Antarctic. Wilson-Barker turned to Sir Clements in the course of conversation and alluding to Bowers said: “Here is a man who will be leading one of those expeditions some day.”

He lived a rough life after passing from the Worcester into the merchant service, sailing five times round the world in the Loch Torridon. Thence he passed into the service of the Royal Indian Marine, commanded a river gunboat on the Irrawaddy, and afterwards served on H.M.S. Fox, where he had considerable experience, often in open boats, preventing the gunrunning which was carried on by the Afghans in the Persian Gulf.

Thence he came to us.

It is at any rate a curious fact, and it may be a significant one, that Bowers, who enjoyed a greater resistance to cold than any man on this expedition, joined it direct from one of the hottest places on the globe. My knowledge is insufficient to say whether it is possible that any trace can be found here of cause and effect, especially since the opposite seems to be the more common experience, in that such people as return from India to England generally find the English winter trying. I give the fact for what it may be worth, remarking only that the cold of an English winter is generally damp, while that of the Antarctic is dry, so far at any rate as the atmosphere is concerned. Bowers himself always professed the greatest indifference not only to cold, but also to heat, and his indifference was not that of a “poseur,” as many experiences will show.

At the same time he was temperamentally one who refused to admit difficulties. Indeed, if he did not actually welcome them he greeted them with scorn, and in scorning went far to master them. Scott believed that difficulties were made to be overcome: Bowers certainly believed that he was the man to overcome them. This self-confidence was based on a very deep and broad religious feeling, and carried conviction with it. The men swore by him both on the ship and ashore. “He’s all right,” was their judgment of his seamanship, which was admirable. “I like being with Birdie, because I always know where I am,” was the remark made to me by an officer one evening as we pitched the tent. We had just been spending some time in picking up a depot which a less able man might well have missed.

As he was one of the two or three greatest friends of my life I find it hard to give the reader a mental picture of Birdie Bowers which will not appear extravagant. There were times when his optimism appeared forced and formal though I believe it was not really so: there were times when I have almost hated him for his infernal cheerfulness. To those accustomed to judge men by the standards of their fashionable and corseted drawing-rooms Bowers appeared crude. “You couldn’t kill that man if you took a poleaxe to him,” was the comment of a New Zealander at a dance at Christchurch. Such men may be at a discount in conventional life; but give me a snowy ice-floe waving about on the top of a black swell, a ship thrown aback, a sledge-party almost shattered, or one that has just upset their supper on to the floor-cloth of the tent (which is much the same thing), and I will lie down and cry for Bowers to come and lead me to food and safety.

Those whom the gods love die young. The gods loved him, if indeed it be benevolent to show your favourites a clear, straight, shining path of life, with plenty of discomfort and not a little pain, but with few doubts and no fears. Browning might well have had Bowers in mind when he wrote of

One who never turned his back, but marched breast forward;

Never doubted clouds would break;

Never dreamed, though right were worsted, wrong would triumph;

Held we fall to rise, are baffled to fight better,

Sleep to wake.

There was nothing subtle about him. He was transparently simple, straightforward and unselfish. His capacity for work was prodigious, and when his own work happened to take less than his full time he characteristically found activity in serving a scientist or exercising an animal. So he used to help to send up balloons with self-recording instruments attached to them, and track the threads which led to them when detached. He was responsible for putting up the three outlying meteorological screens and read them more often than anybody else. At times he looked after some of the dogs because at the moment there was nobody else whose proper job it happened to be, and he took a particular fancy to one of our strongest huskies called Krisravitza, which is the Russian (so I’m told) for “most beautiful.” This fancy originated in the fact that to Kris, as the most truculent of our untamed devils, fell a large share of well-deserved punishment. A living thing in trouble be it dog or man was something to be helped. Being the smallest man in the party he schemed to have allotted to him the largest pony available both for the Depot and Polar Journeys. Their exercise, when he succeeded, was a matter for experiment, for his knowledge of horses was as limited as his love of animals was intense. He started to exercise his second pony (for the first was lost on the floe) by riding him. “I’ll soon get used to him,” he said one day when Victor had just deposited him in the tide-crack, “to say nothing of his getting used to me,” he added in a more subdued voice.

This was open-air work, and as such more congenial than that which had to be done inside the hut. But his most important work was indoors, and he brought to it just the same restless enthusiasm which allowed no leisure for reading or relaxation.

He joined as one of the ship’s officers in London. Given charge of the stores, the way in which he stowed the ship aroused the admiration of even the stevedores, especially when he fell down the main hatch one morning on to the pig-iron below, recovered consciousness in about half a minute, and continued work for the rest of the day as though nothing had happened.

As the voyage out proceeded it became obvious that his knowledge of the stores and undefeatable personality would be of great value to the shore party, and it was decided that he should land, to his great delight. He was personally responsible for all food supplies, whether for home consumption or for sledging, for all sledging stores and the distribution of weights, the loading of sledges, the consumption of coal, the issue of clothing, bosun’s stores, and carpenter’s stores. Incidentally the keeper of stores wanted a very exact knowledge of the cases which contained them, for the drifts of snow soon buried them as they lay in the camp outside.

As time proved his capacity Scott left one thing after another in Bowers’ hands. Scott was a leader of men, and it is a good quality in such to delegate work from themselves on to those who prove their power to shoulder the burden. Undoubtedly Bowers saved Scott a great deal of work, and gave him time which he might not otherwise have been able to spare to interest himself in the scientific work of the station, greatly to its benefit, and do a good deal of useful writing. The two ways in which Bowers helped Scott most this winter were in the preparation of the plans and the working out of the weights of the Southern Journey, which shall be discussed later, and in the routine work of the station, for which he was largely responsible, and which ran so smoothly that I am unable to tell the reader how the stores were issued, or the dinner settled, by what rule the working parties for fetching ice for water and other kindred jobs about the camp were ordered. They just happened, and I don’t know how. I only know that Bowers had the bunk above mine in the hut, and that when I was going to sleep he was generally standing on a chair and using his own bunk as a desk, and I conclude from the numerous lists of stores and weights which are now in my hands that these were being produced. Anyway the job was done, and the fact that we knew nothing about it goes far to prove how efficiently it was carried through.

For him difficulties simply did not exist. I have never known a more buoyant, virile nature. Scott’s writings abound in references to the extraordinary value he placed upon his help, and after the share which he took in the Depot and Winter Journeys it was clear that he would probably be taken in the Polar Party, as indeed proved to be the case. No man of that party better deserved his place. “I believe he is the hardest traveller that ever undertook a Polar Journey, as well as one of the most undaunted.”140

The standard is high.

Bowers gave us two of our best lectures, the first on the Evolution of Sledge Foods, at the end of which he discussed our own rations on the Depot Journey, and made suggestions which he had worked out scientifically for those of the Polar Journey. His arguments were sound enough to disarm the hostility if not to convert to his opinions at least one scientist who had come to hear him strongly of opinion that an untrained man should not discuss so complex a subject. The second lecture, on the Evolution of Polar Clothing, was also the fruit of much work. The general conclusion come to (and this was after the Winter Journey) was that our own clothing and equipment could not be bettered in any important respect, though it must be always understood that the expedition wore windproof clothing and not furs, except for hands and feet. When man-hauling, windproof, I am convinced, cannot be improved upon, but for dog-driving in cold weather I suspect that furs may be better.

The table was cleared after supper and we sat round it for these lectures three times a week. There was no compulsion about them, and the seamen only turned up for those which especially interested them, such as Meares’ vivid account of his journeyings on the Eastern or Chinese borderland of Tibet. This land is inhabited by the “Eighteen Tribes,” the original inhabitants of Tibet who were driven out by the present inhabitants, and Meares told us chiefly of the Lolos who killed his companion Brook after having persuaded him that they were friendly and anxious to help him. “He had no pictures and very makeshift maps, yet he held us really entranced for nearly two hours by the sheer interest of his adventures. The spirit of the wanderer is in Meares’ blood: he has no happiness but in the wild places of the earth. I have never met so extreme a type. Even now he is looking forward to getting away by himself to Hut Point, tired already of our scant measure of civilization.”141

Three lectures a week were too many in the opinion of the majority. The second winter with our very reduced company we had two a week, and I feel sure that this was an improvement. No officer nor seaman, however, could have had too many of Ponting’s lectures, which gave us glimpses into many lands illustrated by his own inimitable slides. Thus we lived every now and then for a short hour in Burma, India or Japan, in scenes of trees and flowers and feminine charm which were the very antithesis of our present situation, and we were all the better for it. Ponting also illustrated the subjects of other lectures with homemade slides of photographs taken during the autumn or from printed books. But for the most part the lecturers were perforce content with designs and plans, drawn on paper and pinned one on the top of the other upon a large drawing-board propped up on the table and torn off sheet by sheet.

From the practical point of view the most interesting evening to us was that on which Scott produced the Plan of the Southern Journey. The reader may ask why this was not really prepared until the winter previous to the journey itself, and the answer clearly is that it was impossible to arrange more than a rough idea until the autumn sledging had taught its lesson in food, equipment, relative reliability of dogs, ponies and men, and until the changes and chances of our life showed exactly what transport would be available for the following sledging season. Thus it was with lively anticipation that we sat down on May 8, an advisory committee as it were, to hear and give our suggestions on the scheme which Scott had evolved in the early weeks of the winter after the adventures of the Depot Journey and the loss of six ponies.

It was on just such a winter night, too, that Scott read his interesting paper on the Ice Barrier and Inland Ice which will probably form the basis for all future work on these subjects. The Barrier, he maintained, is probably afloat, and covers at least five times the extent of the North Sea with an average thickness of some 400 feet, though it has only been possible to get the very roughest of levels. According to the movement of a depot laid in the Discovery days the Barrier moved 608 yards towards the open Ross Sea in 13½ months. It must be admitted that the inclination of the ice-sheet is not sufficient to cause this, and the old idea that the glacier streams flowing down from Inland Plateau provide the necessary impetus is imperfect. It was Simpson’s suggestion that “the deposition of snow on the Barrier leads to an expansion due to the increase of weight.” Some admittedly vague ideas as to the extent and character of the inland ice-sheet ended a clever and convincing paper which contained a lot of good reasoning.