XIV

The Last Winter

Ordinary people snuggle up to God as a lost leveret in a freezing wilderness might snuggle up to a Siberian tiger. …

H. G. Wells

| (I) 5 men dead. | |

|---|---|

| Scott | Oates |

| Wilson | Seaman Evans |

| Bowers | |

| (II) 9 men gone home. | |

|---|---|

| Lieut. Evans | Day |

| Simpson | Forde |

| Meares | Clissold |

| Taylor | Anton |

| Ponting | Lashly |

| (III) 2 men landed. | |

|---|---|

| Archer | Williamson |

| (IV) 13 men at Cape Evans for third year. | |

|---|---|

| Atkinson | Crean |

| Cherry-Garrard | Keohane |

| Wright | Dimitri |

| Debenham | Hooper |

| Gran | Williamson |

| Nelson | Archer |

A quite disproportionately small part of Scott’s Last Expedition was given to Atkinson’s account of the last and worst year any of us survivors spent: someone should have compelled him to write, for he will not do so if he can help it. The problems which presented themselves were unique in the history of Arctic travel, the weather conditions which had to be faced during this last winter were such as had never been met in McMurdo Sound! The sledging personnel had lately undergone journeys, in one case no less than four journeys, of major importance, until they were absolutely worn out. The successful issue of the party was a triumph of good management and good fellowship. The saving clause was that as regards hut, food, heat, clothing and the domestic life generally we were splendidly found. To the north of us, some hundreds of miles away, Campbell’s party of six men must be fighting for their lives against these same conditions, or worse—unless indeed they had already perished on their way south. We knew they must be in desperate plight, but probably they were alive: the point in their favour was that they were fresh men. To the south of us, anywhere between us and the Pole, were five men. We knew they must be dead.

The immediate problem which presented itself was how best to use the resources which were left to us. Our numbers were much reduced. Nine men had gone home before any hint of tragedy reached them. Two men had been landed from the ship. We were thirteen men for this last year. Of these thirteen it was almost certain that Debenham would be unable to go out sledging again owing to an injury to his knee: Archer had come to cook and not to sledge: and it was also doubtful about myself. As a matter of fact our sledging numbers for the last summer totalled eleven, five officers and six men.

We were well provided with transport, having the seven mules sent down by the Indian Government, which were excellent animals, as well as our original two dog-teams: the additional dogs brought down by the ship were with two exceptions of no real sledging value. Our dog-teams had, however, already travelled some 1,500 miles on the Barrier alone, not counting the work they had done between Hut Point and Cape Evans; and, though we did not realize it at this time, they were sick of it and never worked again with that dash which we had come to expect of them.

The first thing which we settled about the winter which lay ahead of us was that, so far as possible, everything should go on as usual. The scientific work must of course be continued, and there were the dogs and mules to be looked after: a night-watch to be kept and the meteorological observations and auroral notes to be taken. Owing to our reduced numbers we should need the help of the seamen for this purpose. We were also to bring out another volume of the South Polar Times on Midwinter Day. The importance of not allowing any sense of depression to become a part of the atmosphere of our life was clear to all. This was all the more necessary when, as we shall see, the constant blizzards confined us week after week to our hut. Even when we did get a fine day we were almost entirely confined to the rocky cape for our exercise and walks. When there was sea-ice it was most unsafe.

Atkinson was in command: in addition, he and Dimitri took over the care of the dogs. Many of these, both those which had been out sledging and those just arrived, were in a very poor state, and a dog hospital was soon built. At this date we had 24 dogs left from the last year, and 11 dogs brought down recently by the ship: three of the new dogs had already died. Lashly was in charge of the seven mules, which were allotted to seven men for exercise: Nelson was to continue his marine biological work: Wright was to be meteorologist as well as chemist and physicist: Gran was in charge of stores, and would help Wright in the meteorological observations: Debenham was geologist and photographer. I was ordered to take a long rest, but could do the zoological work, the South Polar Times, and keep the Official Account of the Expedition from day to day. Crean was in charge of sledging stores and equipment. Archer was cook. Hooper, our domestic, took over in addition the working of the acetylene plant. There was plenty of work for our other two seamen, Keohane and Williamson, in the daily life of the camp and in preparations for the sledging season to come.

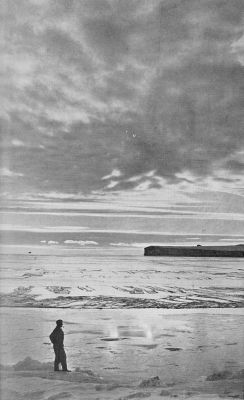

The blizzard which threatened us all the way from Hut Point on May 1 broke soon after we got in. The ice in North Bay, which had been frozen for some time, was taken out on the first day of this blizzard, with the exception of a small strip running close along the shore. The rest followed the next afternoon, when the wind was still rising, and blew in the gusts up to 89 miles an hour. The curious thing was that all this time the air had been quite clear.

This was the second day of the blizzard. The wind continued in violence as the night wore on, and it began to snow, becoming very thick. From 3 a.m. to 4 a.m. the wind was so strong that there was a continuous rattle of sand and stones up against the wall of the hut. The greater part of the time the anemometer head was choked by the drifting snow, and Debenham, whose night-watch it was, had a bad time in clearing it at 4 a.m. During the period when it was working it registered a gust of over 91 miles an hour. While it was not working there came a gust which woke most people up, and which was a far more powerful one, making a regular hail of stones against the wall. The next morning the wind was found to be averaging 104 miles an hour when the anemometer on the hill was checked for three minutes. Later it was averaging 78 miles an hour. This blizzard continued to rage all this day and the next, but on May 6, which was one of those clear beautiful days when it is hard to believe that it can ever blow again, we could see something of the damage to the sea-ice. The centre of the Sound was clear of ice, and the open water stretched to the S. W. of us as far back as Tent Island. We were to have many worse blizzards during this winter, but this particular blow was important because it came at a critical time in the freezing over of the sea, and, once it had been dispersed, the winds of the future never allowed the ice to form again sufficiently thick to withstand the wind forces which obtained.

Thus I find in my diary of May 8: “Up to the present we have never considered the possibility of the sea in this neighbourhood, and the Sound out to the west of us, not freezing over permanently in the winter. But here there is still open water, and it seems quite possible that there may not be any permanent freezing this year, at any rate to the north of Inaccessible Island and this cape. Though North Bay is now frozen over, the ice in it was blown away during the night, and, having been blown back again, is now only joined to the ice-foot by newly frozen ice.”

During this winter the ice formed in North Bay was constantly moving away from the ice-foot, quite independently of wind. I watched it carefully as far as it was possible to do so in the dark. Sometimes at any rate the southern side of the sea-ice moved out not only northwards from the land, but also slightly westwards from the glacier face. To the northeast the ice was sometimes pressed closely up against the glacier. It seemed that the whole sheet was subject to a screw movement, the origin of which was somewhere out by Inaccessible Island. The result was that we often had a series of leads of newly frozen ice stretching out for some forty yards to an older piece of ice, each lead being of a different age. It was an interesting study in the formation of sea-ice, covered at times by very beautiful ice-flowers. But it was dangerous for the dogs, who sometimes did not realize that these leads were not strong enough to bear them. Vaida went in one day, but managed to scramble out on the far side. He was induced to return to the land with difficulty, just before the whole sheet of ice upon which he stood floated out to sea. Noogis, Dimitri’s good leader, wandered away several times during the winter: once at any rate he seems to have been carried off on a piece of ice, and to have managed to swim to land, for when he arrived in camp his coat was full of icy slush: finally he disappeared altogether, all search for him was in vain, and we never found out what had happened.

Vaida was a short-tempered strong animal, who must have about doubled his weight since we came in from One Ton, and he became quite a house-dog this winter, waiting at the door to be patted by men as they went out, and coming in sometimes during the night-watch. But he did not like to be turned out in the morning, and for my part I did not like the job, for he could prove very nasty. We allowed a good many of the dogs to be loose this year, and sometimes, when standing quietly upon a rock on the cape, three or four of the dogs passed like shadows in the darkness, busily hunting the ice-foot for seals: this was the trouble of giving them their freedom, and I regret to say we found many carcasses of seal and Emperor penguins. There was one new dog, Lion, who accompanied me sometimes to the top of the Ramp to see how the ice lay out in the Sound. He seemed as interested in it as I was, and while I was using night-glasses would sit and gaze out over the sea which according to its age lay white or black at our feet. Of course we had a dog called Peary, and another one called Cooke. Peary was killed on the Barrier because he would not pull. Cooke, however, was still with us, and seemed to have been ostracized by his fellows, a position which in some lopsided way he enjoyed. Loose dogs chased him at sight, and when Cooke appeared, and others were about, a regular steeplechase started. He also came up the Ramp with me one day: halfway up he suddenly turned and fled for the hut as hard as he could go: three other dogs came round the rocks in full chase, and they all gave the impression of thoroughly enjoying themselves.

The question of what ought to be done for the best during the coming sledging season must have been in the minds of all of us. Which of the two missing parties were we to try and find? A winter journey to relieve Campbell and his five men was out of the question. I doubt the possibility of such a journey to Evans Coves with fit men: to us at any rate it was unthinkable. Also if we could do the double journey up and down, Campbell could certainly do the single journey down. Add to this that there was every sign of open water under the Western Mountains, though this did not influence us much when the decision was made. The problem as it presented itself to us was much as follows:

Campbell’s Party might have been picked up by the Terra Nova. Pennell meant to have another try to reach him on his way north, and it was probable that the ship would not be able to communicate again with Cape Evans owing to ice: on the other hand it was likely that the ship had not been able to relieve him. It also seemed that he could not have travelled down the coast at this time, owing to the state of the sea-ice. The danger to him and his men was primarily during the winter: every day after the winter his danger was lessened. If we started in the end of October to relieve Campbell, estimating the probable date of arrival of the ship, we judged that we could reach him only five or six weeks before the ship relieved him. All the same Campbell and his men might be alive, and, having lived through the winter, the arrival of help might make the difference between life and death.

On the other hand we knew that the Polar Party must be dead. They might be anywhere between Hut Point and the Pole, drifted over by snow, or lying at the bottom of a crevasse, which seemed the most likely thing to have happened. From the Upper Glacier Depot in 85° 5′ S. to the Pole, that is the whole distance of the Plateau Journey, we did not know the courses they had steered nor the position of their depots, for Lieutenant Evans, who brought back the Last Return Party, was invalided home and neither of the seamen who remained of this party knew the courses.

After the experience of both the supporting parties on their way down the Beardmore Glacier, when we all got into frightfully crevassed areas, it was the general opinion that the Polar Party must have fallen down a crevasse; the weight of five men, as compared with the four men and three men of the other return parties, supported this theory. Lashly was inclined to think they had had scurvy. The true solution never once occurred to us, for they had full rations for a very much longer period of time than, according to their averages to 87° 2′, they were likely to be out.

The first object of the expedition had been the Pole. If some record was not found, their success or failure would forever remain uncertain. Was it due not only to the men and their relatives, but also to the expedition, to ascertain their fate if possible?

The chance of finding the remains of the Southern Party did not seem very great. At the same time Scott was strict about leaving notes at depots, and it seemed likely that he would have left some record at the Upper Glacier Depot before starting to descend the Beardmore Glacier: it would be interesting to know whether he did so. If we went south we must be prepared to reach this depot: farther than that, I have explained, we could not track him. On the other hand, if we went south prepared to go to the Upper Glacier Depot, the number of sledging men necessary, in view of the fact that we had no depots, would not allow of our sending a second party to relieve Campbell.

It was with all this in our minds that we sat down one evening in the hut to decide what was to be done. The problem was a hard one. On the one hand we might go south, fail entirely to find any trace of the Polar Party, and while we were fruitlessly travelling all the summer Campbell’s men might die for want of help. On the other hand we might go north, to find that Campbell’s men were safe, and as a consequence the fate of the Polar Party and the result of their efforts might remain forever unknown. Were we to forsake men who might be alive to look for those whom we knew were dead?

These were the points put by Atkinson to the meeting of the whole party. He expressed his own conviction that we should go south, and then each member was asked what he thought. No one was for going north: one member only did not vote for going south, and he preferred not to give an opinion. Considering the complexity of the question, I was surprised by this unanimity. We prepared for another Southern Journey.

It is impossible to express and almost impossible to imagine how difficult it was to make this decision. Then we knew nothing: now we know all. And nothing is harder than to realize in the light of facts the doubts which others have experienced in the fog of uncertainty.

Our winter routine worked very smoothly. Inside the hut we had a good deal more room than we needed, but this allowed of certain work being done in its shelter which would otherwise have had to be done outside. For instance we cut a hole through the floor of the darkroom, and sledged in some heavy boulders of kenyte lava: these were frozen solidly into the rock upon which the hut was built by the simple method of pouring hot water over them, and the pedestal so formed was used by Wright for his pendulum observations. I was able to skin a number of birds in the hut; which, incidentally, was a very much colder place in consequence of the reduction in our numbers.

The wind was most turbulent during this winter. The mean velocity of the wind, in miles per hour, for the month of May was 24.6 mph; for June 30.9 mph; and for July 29.5 mph. The percentage of hours when the wind was blowing over fresh gale strength (42 mph on the Beaufort scale) for the month of May was 24.5, for June 35, and for July 33 percent of the whole.

These figures speak for themselves: after May we lived surrounded by an atmosphere of raging winds and blinding drift, and the sea at our door was never allowed to freeze permanently.

After the blizzard in the beginning of May which I have already described, the ice round the point of Cape Evans and that in North Bay formed to a considerable thickness. We put a thermometer screen out upon it, and Atkinson started a fish-trap through a hole in it. There was a good deal of competition over this trap: the seamen started a rival one, which was to have been a very large affair, though it narrowed down to a less ambitious business before it was finished. There was a sound of cheering one morning, and Crean came in triumph from his fish-trap with a catch of 25. Atkinson’s last catch had numbered one, but the seals had found his fishing-holes: a new hole caught fish until a seal found it. One of these fish, a Tremasome, had a parasitic growth over the dorsal sheath. External parasites are not common in the Antarctic, and this was an interesting find.

On June 1 Dimitri and Hooper went with a team of nine dogs to and from Hut Point, to see if they could find Noogis, the dog which had left us on our return on May 1. There was plenty of food for him to pick up there. No trace of him could be found. The party reported a bad running surface, no pressure in the ice, as was the case the former year, but a large open working crack running from Great Razorback to Tent Island. There were big snowdrifts at Hut Point, as indeed was already the case at Cape Evans. During the first days of June we got down into the minus thirties, and our spirits rose as the thermometer dropped: we wanted permanent sea-ice.

“Saturday, June 8. The weather changes since the night before last have been, luckily for us, uncommon. Thursday evening a strong northerly wind started with some drift, and this increased during the night until it blew over forty miles an hour, the temperature being −22°. A strong wind from the north is rare, and generally is the prelude of a blizzard. This northerly wind fell towards morning, and the day was calm and clear, the temperature falling until it was −33° at 4 p.m. The barometer had been abnormally low during the day, being only 28.24 at noon. Then at 8 p.m. with the temperature at −36°, this blizzard broke, and at the same time there was a big upward jump of the barometer, which seemed to mark the beginning of the blizzard much more than the thermometer, which did not rise much. The wind during the night was very high, blowing 72 and 66 miles an hour, for hours at a time, and has not yet shown any sign of diminishing. Now, after lunch, the hut is straining and creaking, while a shower of stones rattles at intervals against it: the drift is generally very heavy.”

“Sunday, June 9. The temperature has been higher, about zero, during the day, and the blizzard shows no signs of falling yet. The gusts are still of a very high velocity. A large quantity of ice to the north seems to have gone out: at any rate our narrow strip along the front, which is so valuable to us, will probably be permanent now.”

“Monday, June 10. A most turbulent day. It is very hard to settle down to do anything, read or write, with such a turmoil outside, the hut shaking until we begin to wonder how long it will stand such winds. Most of the time the wind is averaging about sixty miles an hour, but the gusts are far greater, and at times it seems that something must go. Just before lunch I was racking my brains to write an Editorial for the South Polar Times, and had congratulated ourselves on having the sea-ice which is still in North Bay. As we were having lunch Nelson came in and said, ‘The thermometers have gone!’ All the ice in North Bay has gone. The part immediately next to the shore, which has now been in so long, and which was over two feet thick, we had considered sure to stay. On it has gone out the North Bay thermometer screen with its instruments, which was placed 400 yards out, the fish-trap, some shovels and a sledge with a crowbar. The gusts were exceptionally strong at lunch, and the ice must have gone out very quickly. There was no sign of it afterwards, though it was not drifting much and we could see some distance. To lose this ice in North Bay is a great disappointment, for it means so much to us here whether we have ice or water at our doors. We are now pretty well confined to the cape both for our own exercise and that of the mules, and in the dark it is very rough walking. But if the ice in South Bay were to follow, it would be a calamity, cutting us off entirely from the south and all sledging next year. Let us hope we shall be spared this.”

This blizzard lasted for eight days, up till then the longest blizzard we had experienced: “It died as it had lived, blowing hard to the last, averaging 68 miles an hour from the south, and then 56 miles an hour from the north, finally back to the south, and so to calm. To sit here with no noise of wind whistling in the ventilator, calm and starlight outside, and North Bay freezing over once more, is a very great relief.”280

It is noteworthy that this clearance of the ice, as also that in the beginning of May, coincided roughly with the maximum declination of the moon, and therefore with a run of spring tides.

It would be tedious to give any detailed account of the winds and drift which followed, night and day. There were few days which did not produce their blizzard, but in contrast the hours of bright starlight were very beautiful.

“Walking home over the cape in the darkness this afternoon I saw an eruption of Erebus which, compared with anything we have seen here before, was very big. It looked as though a great mass of flame shot up some thousands of feet into the air, and, as suddenly as it rose, fell again, rising again to about half the height, and then disappearing. There was then a great column of steam rising from the crater, and probably, so Debenham asserts, it was not a flame which appeared, but the reflection from a big bubble breaking in the crater. Afterwards the smoke cloud stretched away southwards, and we could not see the end of it.”281

Blizzard followed blizzard, and at the beginning of July we had four days which were the thickest I have ever seen. Generally when you go out into a blizzard the drift is blown from your face and clothes, and though you cannot see your stretched-out hand, especially on a dark winter day, the wind prevents you being smothered. The wind also prevents the land, tents, hut and cases from being covered. But during this blizzard the drift drove at you in such blankets of snow, that your person was immediately blotted out, your face covered and your eyes plugged up. Gran lost himself for some time on the hill when taking the 8 a.m. observations, and Wright had difficulty in getting back from the magnetic cave. Men had narrow escapes of losing themselves, though they were but a few feet from the hut.

When this blizzard cleared the camp was buried, and even on unobstructed surfaces the snowdrifts averaged four feet of additional depth. Two enormous drifts ran down to the sea from either end of the hut. I do not think we ever found some of our stores again, but the larger part we carried up to the higher ground behind us where they remained fairly clear. About this time I began to notice large sheets of anchor ice off the end of Cape Evans, that is to say, ice forming and remaining on the bottom of the open sea. Now also the open water was extending round the cape into the South Bay behind us: but it was too dark to get any reliable idea of the distribution of ice in the Sound. We were afraid that we were cut off from Hut Point, but I do not believe that this was the case; though the open water must have stretched many miles to the south in the middle of the Sound. The days when it was clear enough even to potter about outside the hut were exceptional. God was very angry.

“Sunday, July 14. A blizzard during the night, and after breakfast it was drifting a lot. While we were having service some of the men went over the camp to get ice for water. The sea-ice had been blown out of North Bay, and the men supposed that the sea was open, and would look black, but Crean tells me that they nearly walked over the ice-foot, and, when it cleared later, we saw the sea as white as the ice-foot itself. A strip of ice which was lying out in the Bay last night must have been brought in by the tide, even against a wind of some forty miles an hour. This shows what an influence the tides and currents have in comparison with the winds, for just at this time we are having very big tides. It was blowing and drifting all the morning, and the tide was flowing in, pressing the ice in under the ice-foot to such an extent that later it remained there, though the tide was ebbing and a strong southerly was blowing.”282

Incidentally the bergs which were grounded in our neighbourhood were shifted and broken about considerably by these high winds: also the meteorological screen placed on the Ramp the year before was broken from its upright, which had snapped in the middle, and must have been taken up into the air and so out to sea, for there was no trace of it to be found: Wright lost two doors placed over the entrance to the magnetic cave: when he lifted them they were taken out of his hands by the wind, and disappeared into the air and were never seen again.

So ready was the sea to freeze that there can be little doubt that it already contained large numbers of ice crystals, and time and again I have stood upon the ice-foot watching the tongues of the winds licking up the waters as they roared their way out to sea. Then, with no warning, there would come, suddenly and completely, a lull. And there would be a film of ice, covering the surface of the sea, come so quickly that all you could say was that it was not there before and it was there now. And then down would come the wind again and it was gone. Once when the winter had gone and daylight had returned I stood upon the end of the cape, the air all calm around me, and there, half-a-mile away, a full blizzard was blowing: the islands, and even the berg between Inaccessible Island and the cape, were totally obscured in the thickest drift: the top of the drift, which was very distinct, thinned to show dimly the crest of Inaccessible Island: Turk’s Head was visible and Erebus quite clear. In fact I was just on the edge of a thick blizzard, blowing down the Strait, the side showing as a perpendicular wall about 500 feet high and travelling, I should say, about 40 miles an hour. A roar came out from it of the wind and waves.

The weather conditions were extraordinarily local, as another experience will show. Atkinson and Dimitri were off to Hut Point with the dogs, carrying biscuit and pemmican for the coming Search Journey: I went with them some way, and then left them to place a flag upon the end of Glacier Tongue for surveying purposes. It was clear and bright, and it was easy to get a sketch of the bearings of the islands from this position, which showed how great a portion of the Tongue must have broken off in the autumn of 1911. I anticipated a pleasant walk home, but was somewhat alarmed when heavy wind and drift came down from the direction of the Hutton Cliffs. Wearing spectacles, and being unable to see without them, I managed to steer with difficulty by the sun which still showed dimly through the drift. It was amazing suddenly to walk out of the wall of drift into light airs at Little Razorback Island. One minute it was blowing and drifting hard and I could see almost nothing, the next it was calm, save for little whirlwinds of snow formed by eddies of air drawn in from the north. In another three hundred yards the wind was blowing from the north. On this day Atkinson found wind force 8 and temperature −17° at Hut Point: at Cape Evans the temperature was zero and men were sitting on the rocks and smoking in the sun. Many instances might be given to show how local our weather conditions often were.

There was a morning some time in the middle of the winter when we awoke to one of our usual tearing blizzards. We had had some days of calm, and the ice had frozen sufficiently for the fish-trap to be lowered again. But that it would not stand much of this wind was obvious, and after breakfast Atkinson stuck out his jaw and said he wasn’t going to lose another trap for any dash blizzard. He and Keohane sallied forth on to the ice, lost to our sight immediately in the darkness and drift. They got it, but arrived on the cape in quite a different place, and we were glad to see them back. Soon afterwards the ice blew out.

Much credit is due to the mule leaders that they were able to exercise their animals without hurt. Cape Evans in the dark, strewn with great boulders, with the open sea at your feet, is no easy place to manage a very high-spirited and excitable mule, just out of a warm stable, especially if this is his first outing for several days and the wind is blowing fresh, and you are not sure if your face is frostbitten, and you are quite sure that your hands are. But the exercise was carried out without mishap. The mules themselves were most anxious to go out, and when Pyaree developed a housemaid’s knee and was kept in, she revenged herself upon her more fortunate companions by biting each one hard as it passed her head on its way to and from the door. Gulab was the biggest handful, and Williamson managed him with skill: some of them, especially Lal Khan, were very playful, running round and round their leaders and stopping to paw the ground: Khan Sahib, on the other hand, was bored, yawning continually: it was suggested that he was suffering from polar ennui! Altogether they reflected the greatest credit upon Lashly, who groomed them every day and took the greatest care of them. They were subject to the most violent fits of jealousy, being much disturbed if a rival got undue attention. The dog Vaida, however, was good friends with them all, going down the line and rubbing noses with them in their stalls.

The food of the mules was based upon that given by Oates to the ponies the year before, and the results were successful.

The accommodation given to the dogs in the Terra Nova on the way south is open to criticism. As the reader may remember, they were chained on the top of the deck cargo on the main deck, and of course had a horrible time during the gale, and any subsequent bad weather, which did not however last very long. But it was quite impossible to put them anywhere else, for every square inch between decks was so packed that even our personal belongings for more than two years were reduced to one small uniform case. Any seaman will easily understand that to build houses or shelters on deck over and above what we had already was out of the question. As a matter of fact I doubt whether the dogs had a worse time than we during that gale. In good weather at sea, and at all times in the pack, they were comfortable enough. But future explorers might consider whether they can give their dogs more shelter during the winter than we were able to do. Amundsen, whose Winter Quarters were on the Barrier itself, and who experienced lower temperatures and very much less wind than was our lot at Cape Evans, had his dogs in tents, and let them run loose in the camp during the day. Tents would have gone in the winds we experienced, and I have explained that we had no snow in which we could make houses, as was done by Amundsen in the Barrier.

Our more peaceable dogs were allowed to run loose, especially during this last winter, at the beginning of which we also built a dog hospital. We should have liked to loose them all, but if we did so they immediately flew at one another’s throats. We might perhaps have let them loose if we had first taken the precaution Amundsen took, and muzzled all of them before doing so. The sport of fighting, so his dogs discovered, lost all its charm when they found they could not taste blood, and they gave it up, and ran about unmuzzled and happy. But the slaughter among the seals and penguins would have been horrible with us, and many dogs might have been carried away on the breaking sea-ice. The tied-up ones lay under the lee of a line of cases, each in his own hole. They curled up quite snugly buried in the snowdrift when blizzards were blowing, and lay exactly in the same way when sledging on the Barrier, the first duty of the dog-driver after pitching his own tent being to dig holes for each of his dogs. It may be that these conditions are more natural to them than any other, and that they are warmer when covered by the drifted snow than they would be in any unwarmed shelter: but this I doubt. At any rate they throve exceedingly under these rigorous conditions, soon becoming fat and healthy after the hardest sledge journeys, and their sledging record is a very fine one. We could not have built them a hut; as it was, we left our magnetic hut, a far smaller affair, in New Zealand, for there was no room to stow it on the ship. I would not advise housing dogs in a hut built with a lean-to roof as an annex to the main living-hut, but this would be one way of doing it if you are prepared to stand the noise and smell.

The dog-biscuits, provided by Spratt, weighed 8 oz. each, and their sledging ration was 1½ lbs. a day, given to them after they reached the night camp. We made seal pemmican for them and tried this when sledging, as an occasional variation on biscuit, but they did not thrive on this diet. The oil in the biscuits caused purgation, as also did the pemmican: the fat was partly undigested and the excreta were eaten. The ponies also ate their excreta at times. Certain dogs were confirmed leather eaters, and we carried chains for them: on camping, these dogs were taken out of their canvas and rawhide harnesses, and attached to the sledge by the chains, care being taken that they could not get at the food on the sledge. When sledging, Amundsen gave his dogs pemmican but I do not know what else: he also fed dog to dog: I do not know whether we could have fed dog to dog, for ours were Siberian dogs which, I am told, will not eat one another. At Amundsen’s winter quarters he gave them seal’s flesh and blubber one day, and dried fish the next.283 On the long voyage south in the Fram, he fed his dogs on dried fish, and three times a week gave them a porridge of dried fish, tallow, and maize meal boiled together.284 At Cape Evans or at Hut Point our dogs were given plenty of biscuit some evenings, and plenty of fresh frozen seal at other times.

Our worst trouble with the dogs came from far away—probably from Asia. There are references in Scott’s diary to four dogs as attacked by a mysterious disease during our first year in the South: one of these dogs died within two minutes. We lost many more dogs the last year, and Atkinson has given me the following memorandum upon the parasite, a nematode worm, which was discovered later to be the cause of the trouble:

“Filaria immitis.—A certain proportion of the dogs became infected with this nematode, and it was the cause of their death, mainly in the second year. It was present at the time the expedition started (1910) all down the Pacific side of Asia and Papua, and there was an examination microscopically of all dogs imported at this time into New Zealand. The secondary host is the mosquito Culex.

“The symptoms varied. The onset was usually with intense pain, during which the animal yelled and groaned: this was cardiac in origin and referable to the presence of the mature form in the beast. There was marked haematuria, and the animals were anaemic from actual loss of haemoglobins. In nearly all cases there was paralysis affecting the hindquarters during the later stages, which tended to spread upwards and finally ended in death.

“The probable place of infection was Vladivostok before the dogs were put on board ship and deported to New Zealand. The only method of coping with the disease is prevention of infection in infected areas. It is probable that the mosquitoes would not bite after the dog’s coat had been rubbed with paraffin: or mosquito netting might be placed over the kennels, especially at night time. The larval forms were found microscopically in the blood, and one mature form in the heart.”

We were too careful about killing animals. I have explained how Campbell’s party was landed at Evans Coves. Some of the party wanted to kill some seals on the off chance of the ship not turning up to relieve them. This was before they were in any way alarmed. But it was decided that life might be taken unnecessarily if they did this—and that winter this party nearly died of starvation. And yet this country has allowed penguins to be killed by the million every year for Commerce and a farthing’s worth of blubber.

We never killed unless it was necessary, and what we had to kill was used to the utmost both for food and for the scientific work in hand. The first Emperor penguin we ever saw at Cape Evans was captured after an exciting chase outside the hut in the middle of a blizzard. He kept us busy for days: the zoologist got a museum skin, showing some variation from the usual coloration, a skeleton, and some useful observation on the digestive glands: the parasitologist got a new tapeworm: we all had a change of diet. Many a pheasant has died for less.

There were plenty of Weddell seal round us this winter, but they kept out of the wind and in the water for the most part. The sea is the warm place of the Antarctic, for the temperature never falls below about 29° F, and a seal which has been lying out on the ice in a minus thirty temperature, and perhaps some wind, must feel, as he slips into the sea, much the same sensations as occur to us when we walk out of a cold English winter day into a heated conservatory. On the other hand, a seaman went out into North Bay to bathe from a boat, in the full sun of a midsummer day, and he was out almost as soon as he was in. One of the most beautiful sights of this winter was to see the seals, outlined in phosphorescent light, swimming and hunting in the dark water.

We had lectures, but not as many as during the previous winter when they became rather excessive: and we included outside subjects. We read in many a polar book of the depressions and trials of the long polar night; but thanks to gramophones, pianolas, variety of food, and some study of the needs both of mind and body, we suffered very little from the first year’s months of darkness. There is quite a store of novelty in living in the dark: most of us I think thoroughly enjoyed it. But a second winter, with some of your best friends dead, and others in great difficulties, perhaps dying, when all is unknown and everyone is sledged to a standstill, and blizzards blow all day and all night, is a ghastly experience. This year there was not one of our company who did not welcome the return of the sun with thankfulness: all the more so since he came back to a land of blizzards and made many of our difficulties more easy to tackle. Those who got little outside exercise were more affected by the darkness than others. This last year, of course, the difficulties of getting sufficient outdoor exercise were much increased. Variety is important to the man who travels in polar regions: at all events those who went away on sledging expeditions stood the life more successfully than those whose duties tied them to the neighbourhood of the hut.

Other things being equal, the men with the greatest store of nervous energy came best through this expedition. Having more imagination, they have a worse time than their more phlegmatic companions; but they get things done. And when the worst came to the worst, their strength of mind triumphed over their weakness of body. If you want a good polar traveller get a man without too much muscle, with good physical tone, and let his mind be on wires—of steel. And if you can’t get both, sacrifice physique and bank on will.

Note

A lecture given at this time by Wright on Barrier Surfaces is especially interesting with relation to the Winter Journey and the tragedy of the Polar Party. The general tend of friction set up by a sledge-runner upon snow of ordinary temperature may be called true sliding friction: it is probable that the runners melt to an infinitesimal degree the millions of crystal points over which they glide: the sledge is running upon water. Crystals in such temperatures are larger and softer than those encountered in low temperatures. It is now that halos may be seen in the snow, almost reaching to your feet as you pull, and moving forward with you: we steered sometimes by keeping these halos at a certain angle to us. My experience is that the best pulling surface is at an air temperature of about +17° F: Wright’s experience is that below +5° during summer temperatures on the Barrier the surface is fairly good, that between +5° and +15° less good, and between +15° and +25° best. The worst is from +25° upwards, the worst of all being round about freezing point.

As the temperature became high the amount of ice melted by this sliding friction was excessive. It was then that we found ice forming upon the runners, often in almost microscopic amounts, but nevertheless causing the sledges to drag seriously. Thus on the Beardmore we took enormous care to keep our runners free from ice, by scraping them at every halt with the back of our knives. This ice is perhaps formed when the runners sink into the snow to an unusual depth, at which the temperature of the snow is sufficiently low to freeze the water previously formed by friction or radiation from the sun on to a dark runner.

In very low temperatures the snow crystals become very small and very hard, so hard that they will scratch the runners. The friction set up by runners in such temperatures may be known as rolling friction, and the effect, as experienced by us during the Winter Journey and elsewhere, is much like pulling a sledge over sand. This rolling friction is that of snow crystal against snow crystal.

If the barometer is rising you get flat crystals on the ice, if it is falling you get mirage and a blizzard. When you get mirage the air is actually coming out of the Barrier. Thus far Wright’s lecture.

Since we returned I have had a talk with Nansen about the sledge-runners which he recommends to the future explorer. The ideal sledge-runner combines lightness and strength. He tells me that he would always have metal runners in high temperatures in which they will run better than wood. In cold temperatures wood is necessary. Metal is stronger than wood with same weight. He has never used, but he suggests the possible use of, aluminium or magnesium for the metal. And he would also have wooden runners with metal runners attached, to be used alternately, if needed.

The Discovery Expedition used German silver, and it failed: Nansen suggests that the failure was due to the fact that these runners were fitted at home. The effect of this is that the wood shrinks and the German silver is not quite flat: the fitting should be done on the spot. Nansen did this himself on the Fram, and the result was excellent. [I believe that these Discovery runners were not a continuous strip of metal but were built up in strips, which tore at the points of junction.] Before it is fitted, German silver should be heated red hot and allowed to cool. This makes it more ductile, like lead, and therefore less springy: the metal should be as thin as possible.

As runners melt the crystals and so run on water, metal is unsuitable for cold snow. For low temperatures, therefore, Nansen would have wooden runners under the metal, the metal being taken off when cold conditions obtained. He would choose such wood as is the best conductor of heat. He tried birch wood in the first crossing of Greenland, but would not recommend it as being too easily broken. In the use of oak, ash, maple, and doubtless also hickory, for runners, the rings of growth of the tree should be as far apart as possible: that is to say, they should be fast growing. Ash with narrow rings breaks. There is ash and ash: American ash is no good for this purpose; some Norwegian ash is useful, and some not. Our own sledges with ash runners varied enormously. The runners of a sledge should curve slightly, the centre being nearest to the snow. The runners of ski should curve also slightly, in this case upwards in the centre, i.e. from the snow. This is done by the way the wood is cut. Wood always dries with the curve from the heart towards the outside of the tree.

During our last year we had six new Norwegian sledges twelve feet long, brought down by the ship, with tapered runners of hickory which were 3¾ inches broad in the fore part and 2¼ inches only at the stern. I believe that this was an idea of Scott, who considered that the broad runner in front would press down a path for the tapered part which followed, the total area of friction being much less. We took one of them into South Bay one morning and tried it against an ordinary sledge, putting 490 lbs. on each of them. The surface included fairly soft as well as harder and more rubbly going. There was no difference of opinion that the sledge with the tapered runners pulled easier, and later we used these sledges on the Barrier with great success.

If some instrument could be devised to test sledges in this way it would be of very great service. No team of men can make an exact estimate of the run of their own sledge, let alone the sledge which your pony or your dogs are pulling. Yet sledges vary enormously, and it would be an excellent thing for a leader to be able to test his sledges before buying them, and also to be able to pick out the best for his more important sledge journeys. I believe it can be done by attaching some kind of balance between the sledge and the men pulling it.

Other points mentioned by Nansen are as follows:

Tarred ski are good: the snow does not stick so much. [This probably refers to the Norwegian compound known as fahrt.] But he does not recommend tarred runners for sledges. Having had experience of a tent of Chinese silk which would go into his pocket but was very cold, he recommends a double tent, the inner lining being detached so that ice could be shaken from both coverings. He suggests the possibility of a woollen lining being warmer than cotton or silk or linen. I am, however, of opinion that wool would collect more moisture from the cooker, and it certainly would be far more difficult to shake off the ice. For four men he would have two two-men sleeping-bags and a central pole coming down between them, and the floor-cloth made in one piece with the tent. For three men a three-man sleeping-bag: e.g. for such a journey as our Winter Journey. He would not brush rime, formed upon the tent by the steam from the cooker and breath, from the inside of tent before striking camp. The more of it the warmer. He considers that two- or three-men sleeping-bags are infinitely warmer than single bags: objections of discomfort are overcome, for you are so tired you go to sleep anyway. I would, however, recommend the explorer to read Scott’s remarks upon the same subject before making up his mind.285